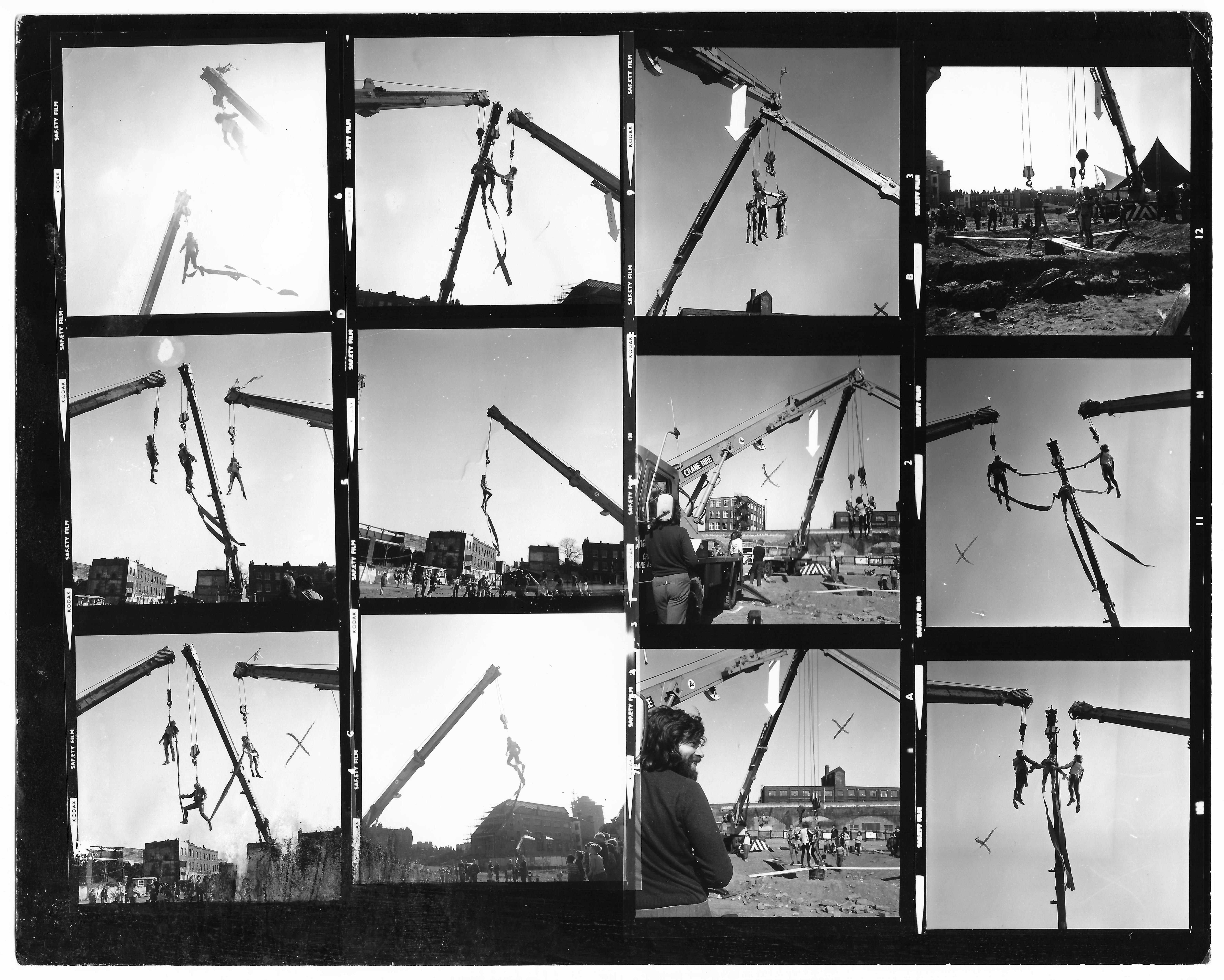

Crane Ballet, photomontage by Jorge Lewinski, 1971. Leopoldo Maler Archive. © and courtesy the artist

Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

In 1971, the choreographic work Crane Ballet, by Argentine artist Leopoldo Maler, was performed in London as part of the Camden Arts Festival. A delicate dance between stunt performers, industrial machines, and their operators, Maler’s first public-facing performance investigated the possibilities of industrial machinery through dance, expanding the range of movement and uses for functional objects. Following Maler’s explorations of this idea, from his background in theater to his relationships with other British and Argentine artists, art historian Agustín Díez Fischer examines bodily extension and mediated reconstruction in Maler’s work.

Fig. 1. Front cover of the Sunday Times, London, April 11, 1971. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © and courtesy the artist

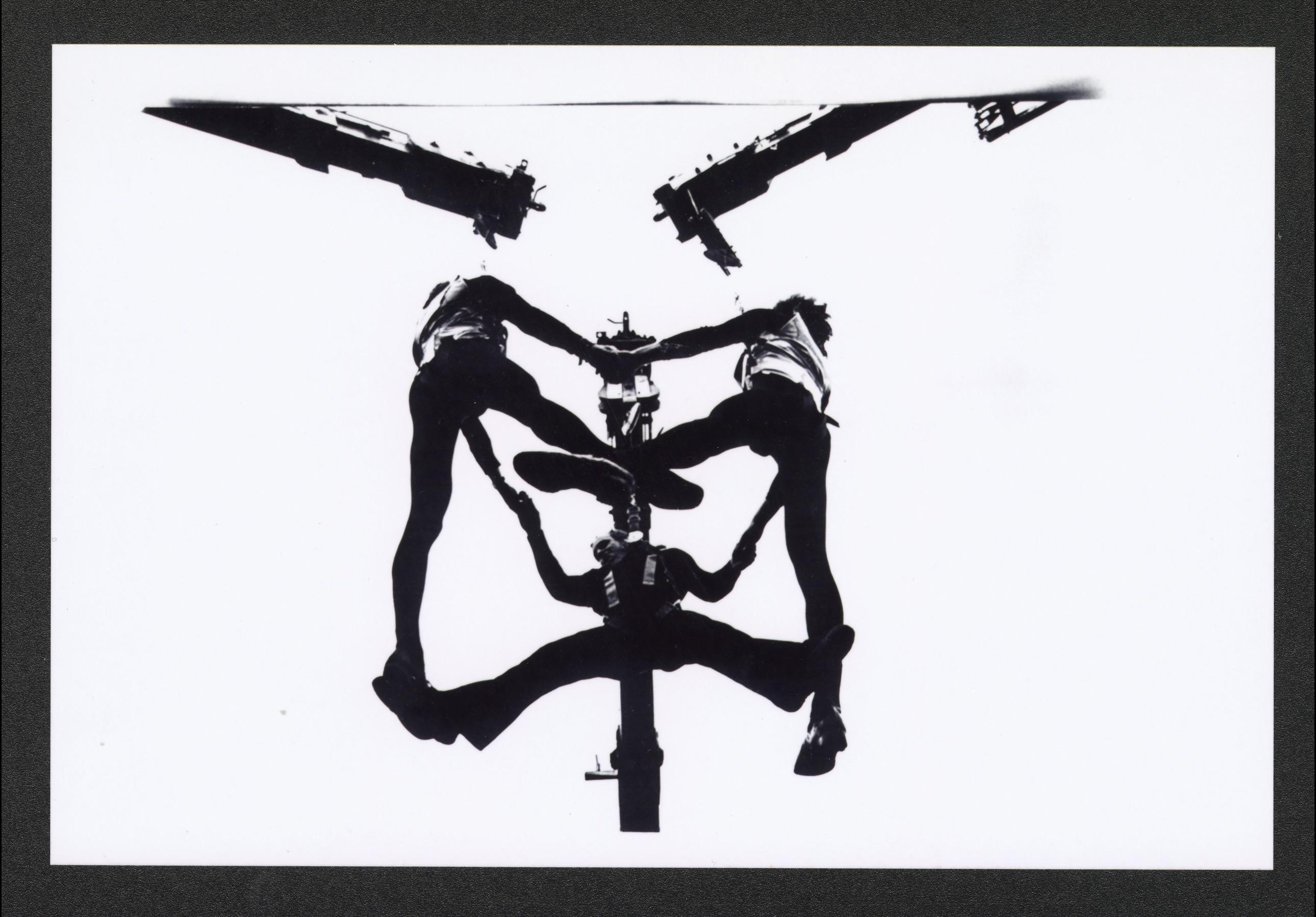

Readers of the British newspaper the Sunday Times found an unusual image on the front page on April 11, 1971: amid news of arms sales to Libya and conflicts in Pakistan, there was a photograph of three dancers hanging from cranes under the sky of London’s Kentish Town (fig. 1). The “crane ballet,” as described by the caption, was a production by Argentine artist Leopoldo Maler, commissioned by the Swiss Cottage Library as one of the many artistic activities that were part of the Camden Arts Festival taking place that Easter weekend. From the little information that could be gleaned from the newspaper photograph, readers could not anticipate how the spectacular image of the dancers enabled a dialogue between that wasteland in London and the avant-garde experiences of a distant metropolis: Buenos Aires. 1 As I will show in this text, Crane Ballet linked those worlds through an experimental dance piece where bodies and machines, languages and latitudes, were combined.

After settling in London in 1961 to work for the BBC, Maler spent the 1960s and 1970s living alternately in England and Argentina. 2 In Buenos Aires, he was part of the experimental scene of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella (ITDT), where he made the film recording of La Menesunda (Mayhem, 1965), the renowned work by Marta Minujín and Rubén Santantonín, and produced his first theater piece, Caperucita Rota (Broken Red Riding Hood, 1966), which he presented at the ITDT’s Centro de Experimentación Audiovisual. By the time he staged the ballet in Camden in 1971, Maler had already studied with the Royal Shakespeare Company, directed a stage adaptation of Palabras ajenas (Argentine artist León Ferrari’s literary collage, whose title translates to “The Words of Others”) and developed a multidisciplinary work that included films, installations and stage works. 3 Crane Ballet was not only a work where many of Maler’s explorations of the previous decade converged but also the piece that would initiate his productions for the public space. 4

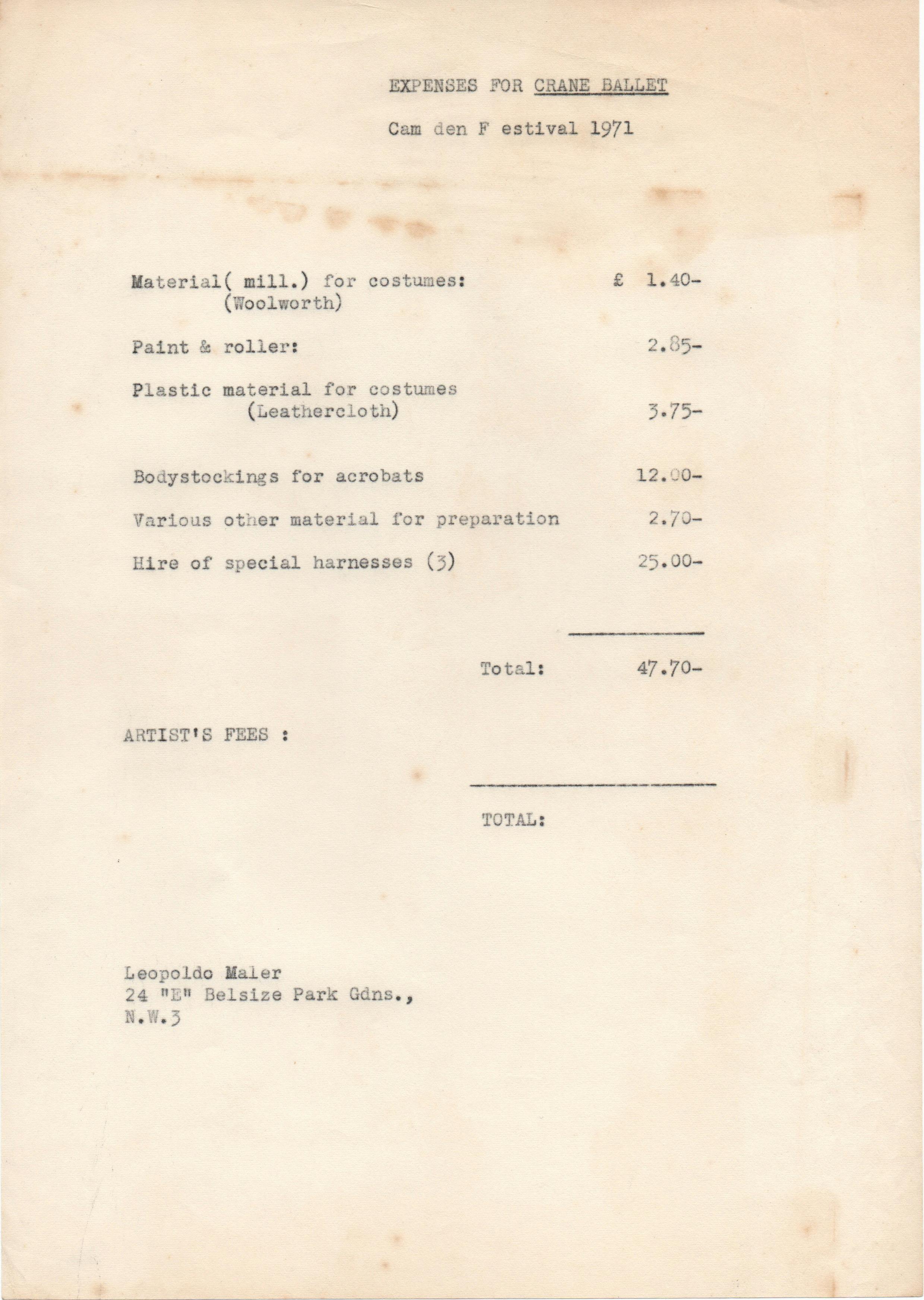

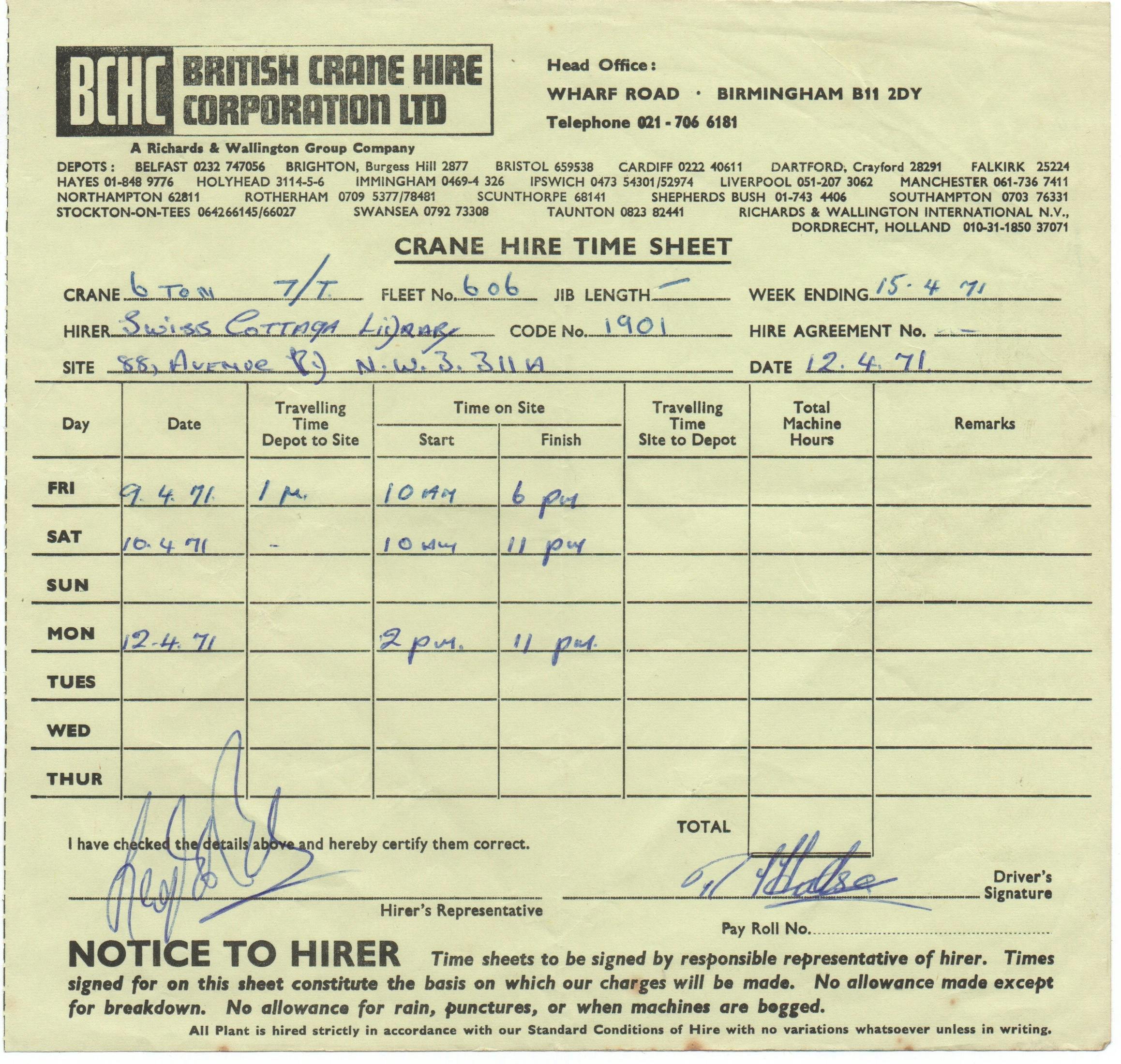

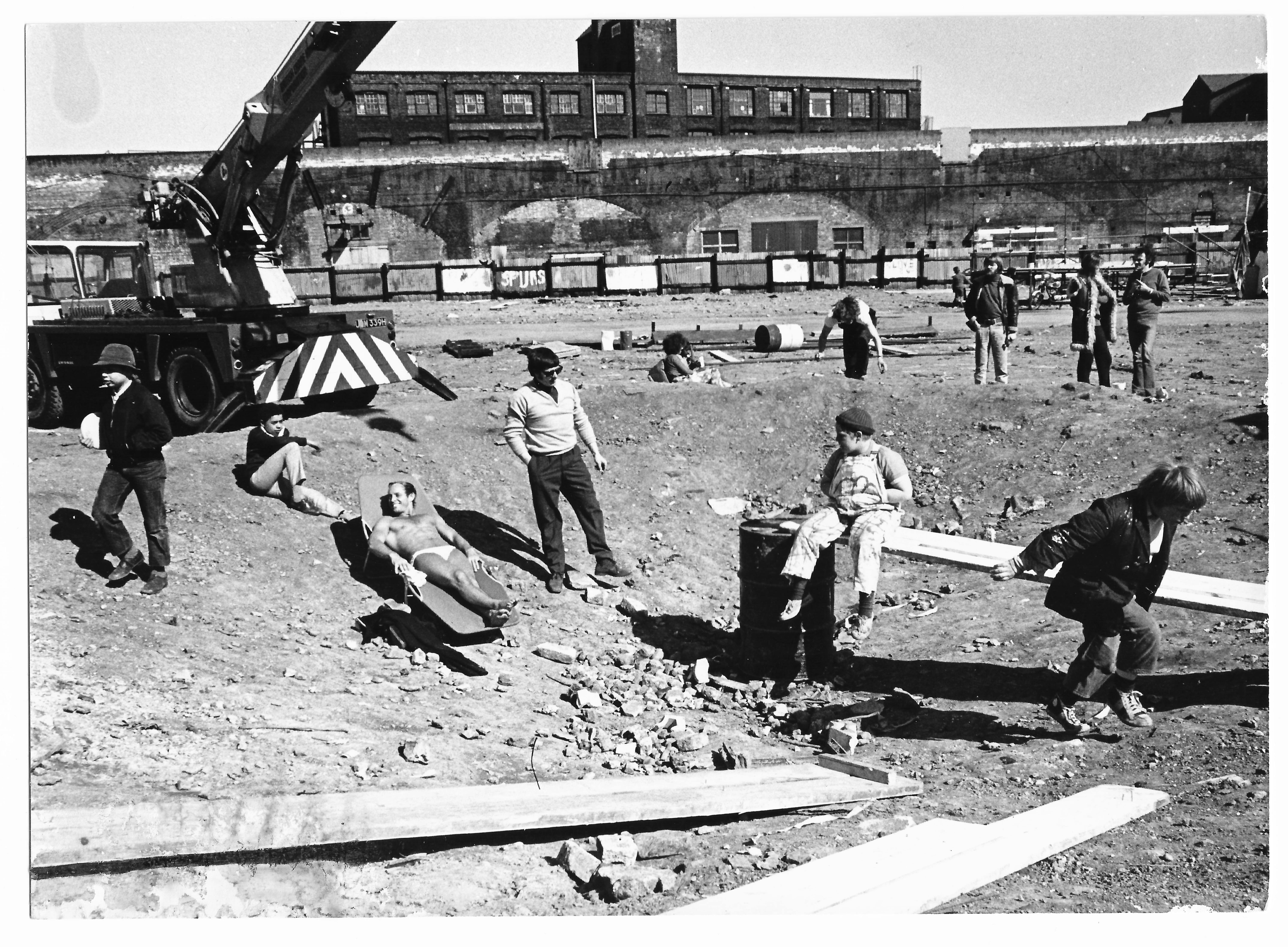

The documentation preserved at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) allows us to reconstruct the ballet and its production. ISLAA’s archive holds the expense records and purchase invoices for the harnesses and other materials needed for the dancers’ costumes (fig. 2). There, we can see the prices and other details of the crane rental for April 9, 10, and 12, 1971 (fig. 3). The first day was devoted to rehearsals, while the two festival performances took place on Saturday April 10. On the last day, Monday April 12, they shot a 16mm film, preserved in the collection in DVD format. 5 This film does not record the performances made for the festival but, rather, a production carried out by the BBC for television broadcasting. 6

Static space, existing in a sort of tension resulting from two opposing forces, was a leitmotif of Maler’s work, both for on-stage movements and for determining the audience’s place in his performances.

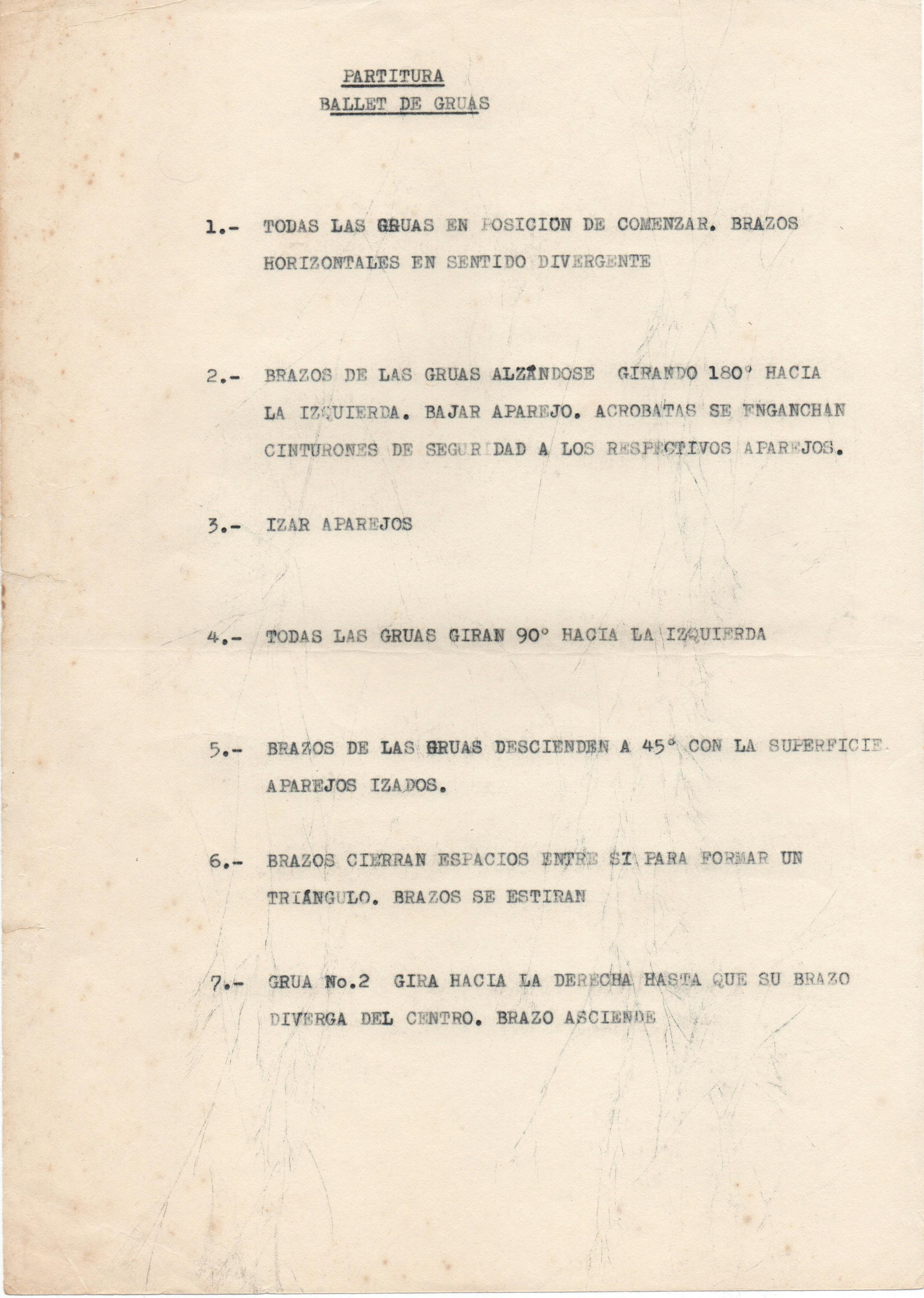

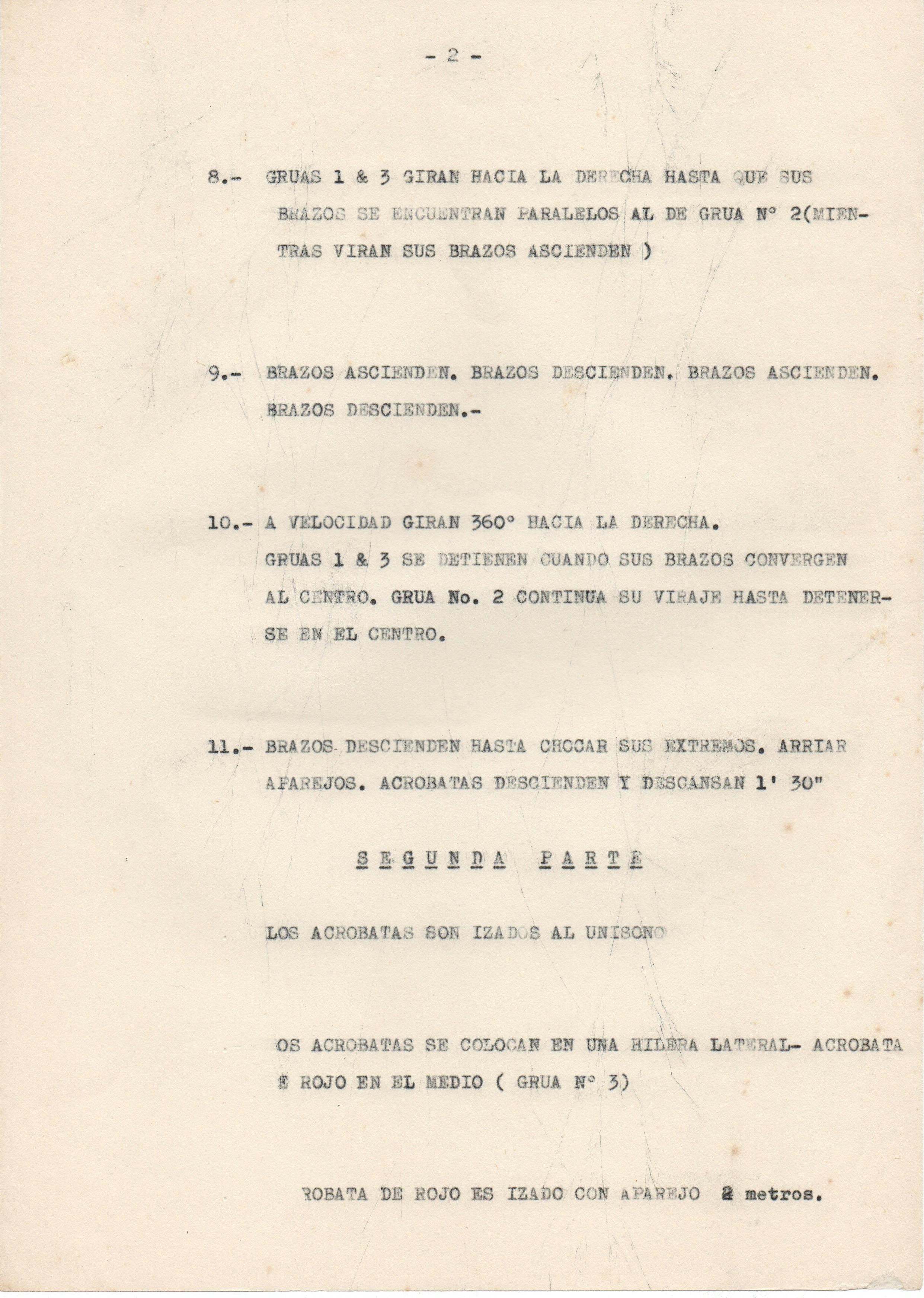

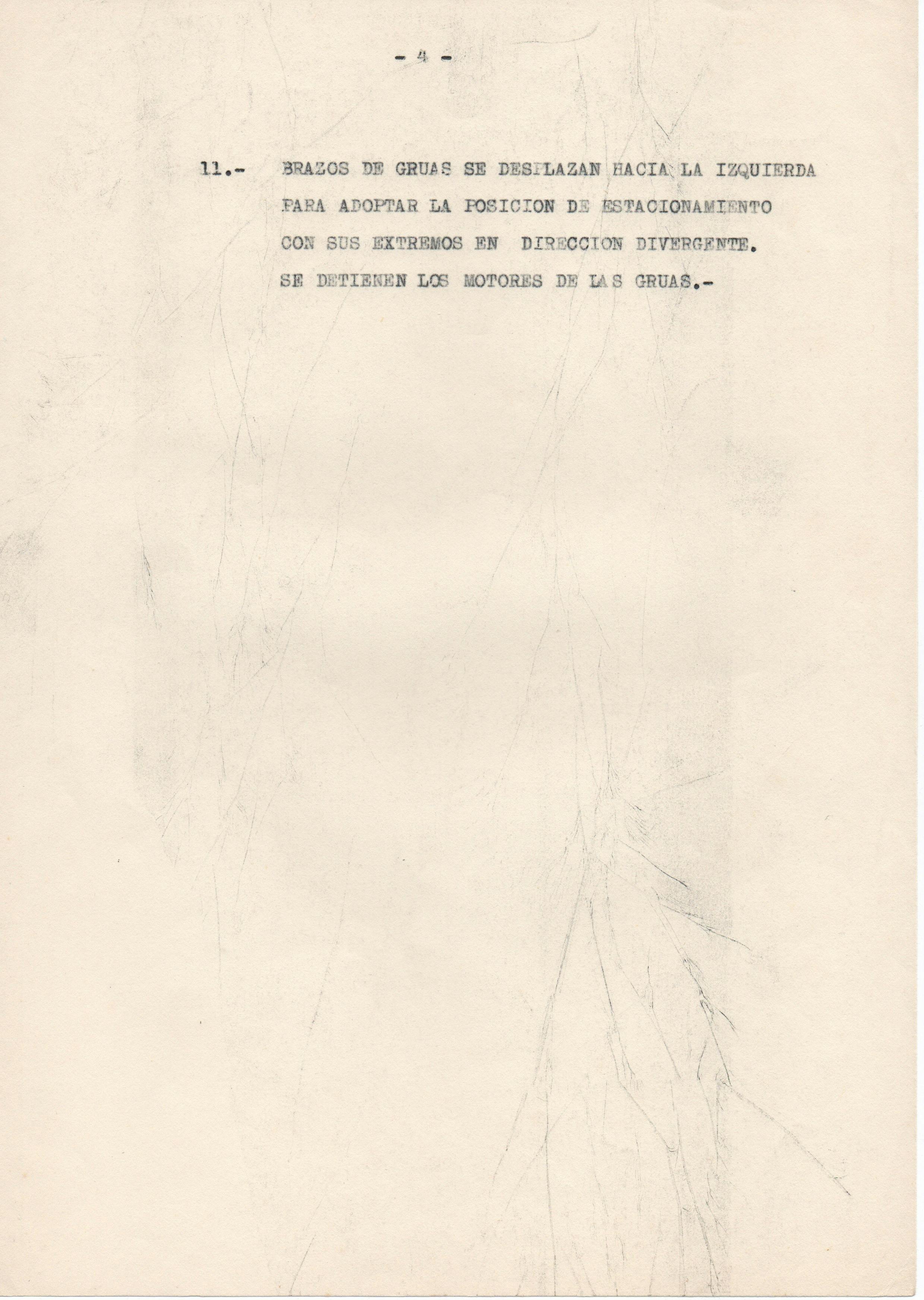

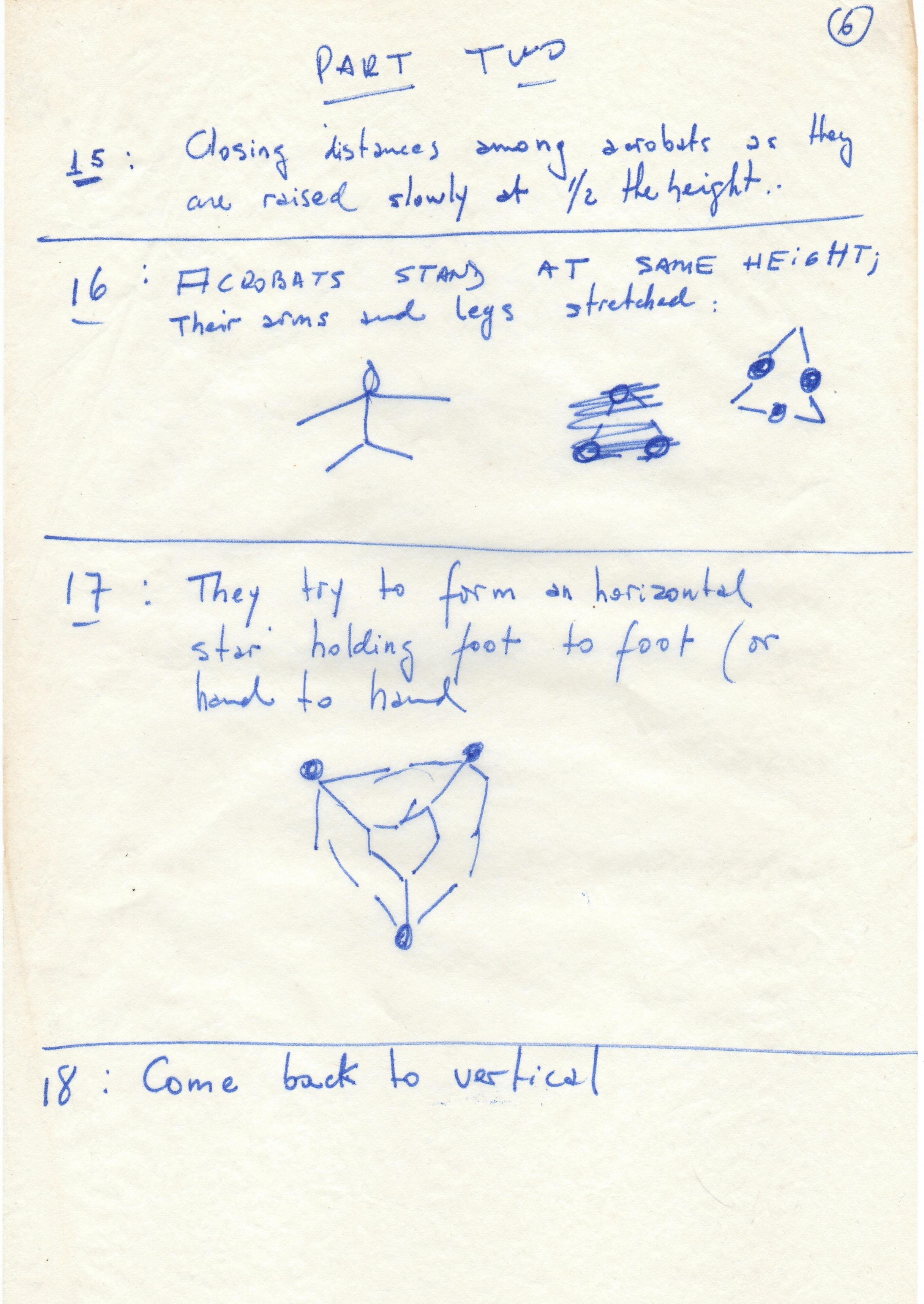

The collection also includes a typed document detailing the ballet’s dance steps, titled “Partitura: Ballet de Grúas” (Score: Crane Ballet), and three other handwritten documents (one in Spanish and two in English) that describe each of the movements in greater detail (figs. 4 and 5). There is also a collection of black-and-white photographs that document the performance. 7 In these photos, we see the dancers (originally trained as stunt actors) alongside the audience, which includes entire families that attended the festival (figs. 6–8). We also see two arrow-shaped signs with the inscriptions “Sky” and “No Cloud,” which were used during the event (figs. 9 and 10).

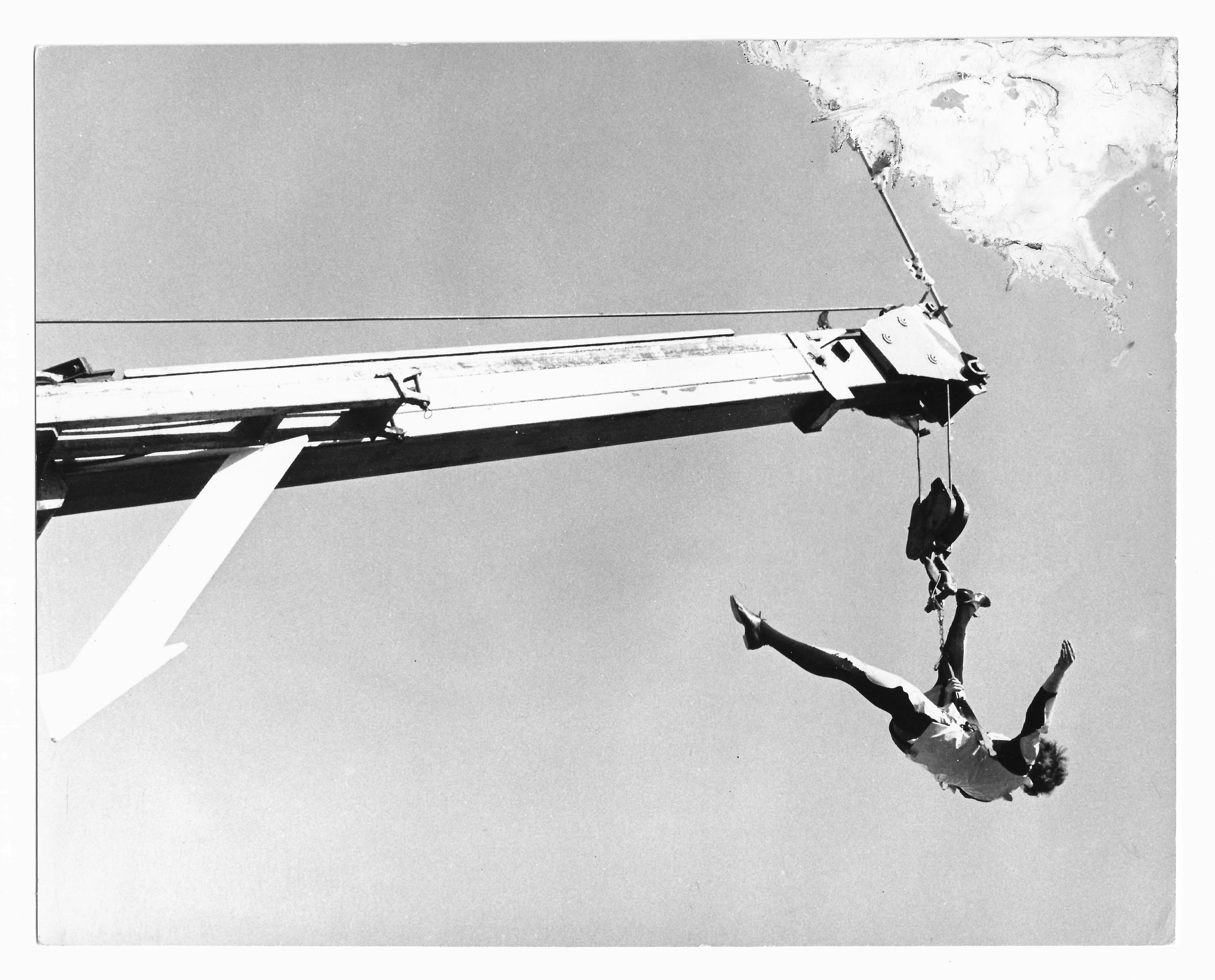

The artist’s specification of each movement places Crane Ballet alongside other choreographies that move away from improvisation, opting instead for a predetermined sequence of steps. Organized in two parts, the work comprises three movements. In the first, the focus lies on the cranes, which are operated in a coordinated manner to extend booms and raise and lower the hooks from which the actors are suspended from harnesses. In the second movement, the focus shifts to the dancers, who create geometric shapes with their arms and legs and place their bodies in different positions, including inverted or horizontal postures. Finally, the dancers and cranes move together. At one point, one of the cranes begins to rotate, increasing its speed with each turn, while the dancer pretends to run in the air. In one of the last scenes, the dancers (dressed in special fabrics in red, white, and blue) unfurl large plastic cloths that had been rolled up and hidden in their arms and legs, creating the effect that their limbs have lengthened, acquiring superhuman dimensions (figs. 11–15). 8

According to Maler, Crane Ballet was guided by two central ideas. 9 On the one hand, the creation of a static space through the combination of two opposing movements. One example of this is the simultaneity between the lifting of the crane boom and the lowering of the hook, wich caused the dancer’s body to stay in the same position. That static space, existing in a sort of tension resulting from two opposing forces, was a leitmotif of Maler’s work, both for on-stage movements and for determining the audience’s place in his performances. In contrast to participatory theater, the Argentine artist sought to create a moment of stillness—yet in tension—that would trigger a process of reflection in the viewer. 10

The other idea that guided Crane Ballet was to expand human possibilities of occupying space and propose a creative use of utilitarian technologies. In this sense, the performance engaged in a direct dialogue with the ideas of the Artist Placement Group, created by British artists Barbara Steveni and John Latham with the aim of rethinking the role of the artist in society and in production processes. 11 About a year before Crane Ballet, in December 1969, Maler proposed to Latham himself to observe activity in a factory and create a choreography from them that could be performed in that same factory space. 12 The movements of the workers and the way they used the machinery could be creatively harnessed and redeployed, freeing them from their utilitarian aims. The role of the artist, in that sense, was to be a catalyst for these possibilities.

Dance offered infinite possibilities for that purpose, which Maler had already begun exploring in his works X-IT (1969) and X-IT2 (1970) (figs. 16–17). Presented at London’s recently opened venue The Place, these performance pieces were commissioned and performed by the London Contemporary Dance Theatre. 13 X-IT and X-IT2 consisted of a series of scenes and featured two motorized elevators that choreographed their movements with the dancers on stage. 14 Alongside these works, Maler also published a manifesto in which he declared that all movement could become dance, and that, through it, it was possible to transform our own perception:

The landing of man on the moon has shown millions that we can move in a way not previously experienced. Therefore, an extraordinary scientific achievement has, in its way, become an event in the art of dance. If that choreography is the organization of movement within a certain space and an accepted set of rules, it follows that a football match or a traffic flow could then become a "ballet." Considering our mechanized society, one might say that it eliminates the "variable," the total freedom that is the most desirable element in the realm of Art. However, by changing its operative context, a piece of machinery like a forklift truck can dispose of the repetitive and incorporate the unexpected.

Leopoldo Maler “’X’IT” (London: The Place, 1969). I have made minor clarifying changes to the text, with the author’s permission.

Alongside its connections with the British scene and the works that Maler was producing in the sixties, Crane Ballet also engages in a dialogue with the Argentine avant-garde and the interests of the artists who participated in the ITDT. More specifically, Maler was familiar with contemporary dance, particularly with the work of dancer Graciela Martínez, who successfully performed at the Arts Lab in London at the end of 1967. 15 Although their explorations were different, Martínez’s work with objects such as bathtubs and tricycles, presents us with a possible dialogue with Maler’s projects.

The movements of the workers and the way they used the machinery could be creatively harnessed and redeployed, freeing them from their utilitarian aims. The role of the artist, in that sense, was to be a catalyst for these possibilities.

The idea of drawing connections between factory work and the field of art had also been explored in the Argentine scene. In 1968, Argentine artist Óscar Bony showed La familia obrera (The Working-Class Family), where a real family, consisting of a factory worker, a housewife, and their son, were presented in the context of an art exhibition at the ITDT. Both Maler and Bony compensated their workers with double their usual pay. But their works differed in their treatment of the worker's knowledge. In Bony’s piece, the focus was on family ties (although compensated as labor). For Maler, on the other hand, it was the workers’ skills, in particular their ability to operate the crane, that played a central role in the creation of the work. 16 That knowledge, used in a completely different way, could be freed from its utilitarian functions.

Finally, Crane Ballet also offers the possibility of a comparative analysis from the perspective of contemporary artistic practices—from the relationship between the human and the non-human to different explorations of the body. 17 The circulation of documentation on Leopoldo Maler will undoubtedly play a central role in generating new readings that connect his work with recent productions. In the case of documents related to Crane Ballet, in recent years the film produced by the BBC has been the almost exclusive protagonist in the circulation of the work in galleries and museums (fig. 18). However, this audiovisual material lends itself to a very specific reading, according to which the work is shown almost as if it were a simulacrum of a classical ballet performance. 18 The film sets the movements of the cranes to a fragment of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker. At the request of the producers, the film also shows Maler dressed in tails and waving his baton, as if he were an orchestra conductor. 19 Over a span of less than four minutes, the film shows images of the audience, the performers, the cranes, and the artist, including a short interview with him at the end of the tape. 20

It is remarkable that film has been the predominant form of display for Crane Ballet. Perhaps, in line with Maler’s previous works, the film can be seen as a reflection on the media and its construction of reality. 21 Under this prism,Crane Ballet can be considered to be in dialogue with a group of works by Argentine artists such as Roberto Jacoby, Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escari, and Marta Minujín, all of them influenced by the teachings of theorist Oscar Masotta and the readings of Marshall McLuhan. 22 If, as Philip Auslander suggests, documents are not mere recordings of past events but instead produce the event as performance, the question would then be how the filmic record constructs Crane Ballet as performance, and how other documents held in the archive do the same. 23 In other words, it becomes a journey of meanings and interpretations that expand from the photograph in the Sunday newspaper to the ways in which documentary records of Latin American art circulate.