Edgardo Giménez, Amor (Mariposa) (Love [Butterfly]), 1970. Screenprint 10 1/8 × 9 1/8 in. (25.7 × 23.2 cm). © the artist. Courtesy the artist and MCMC Galería. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

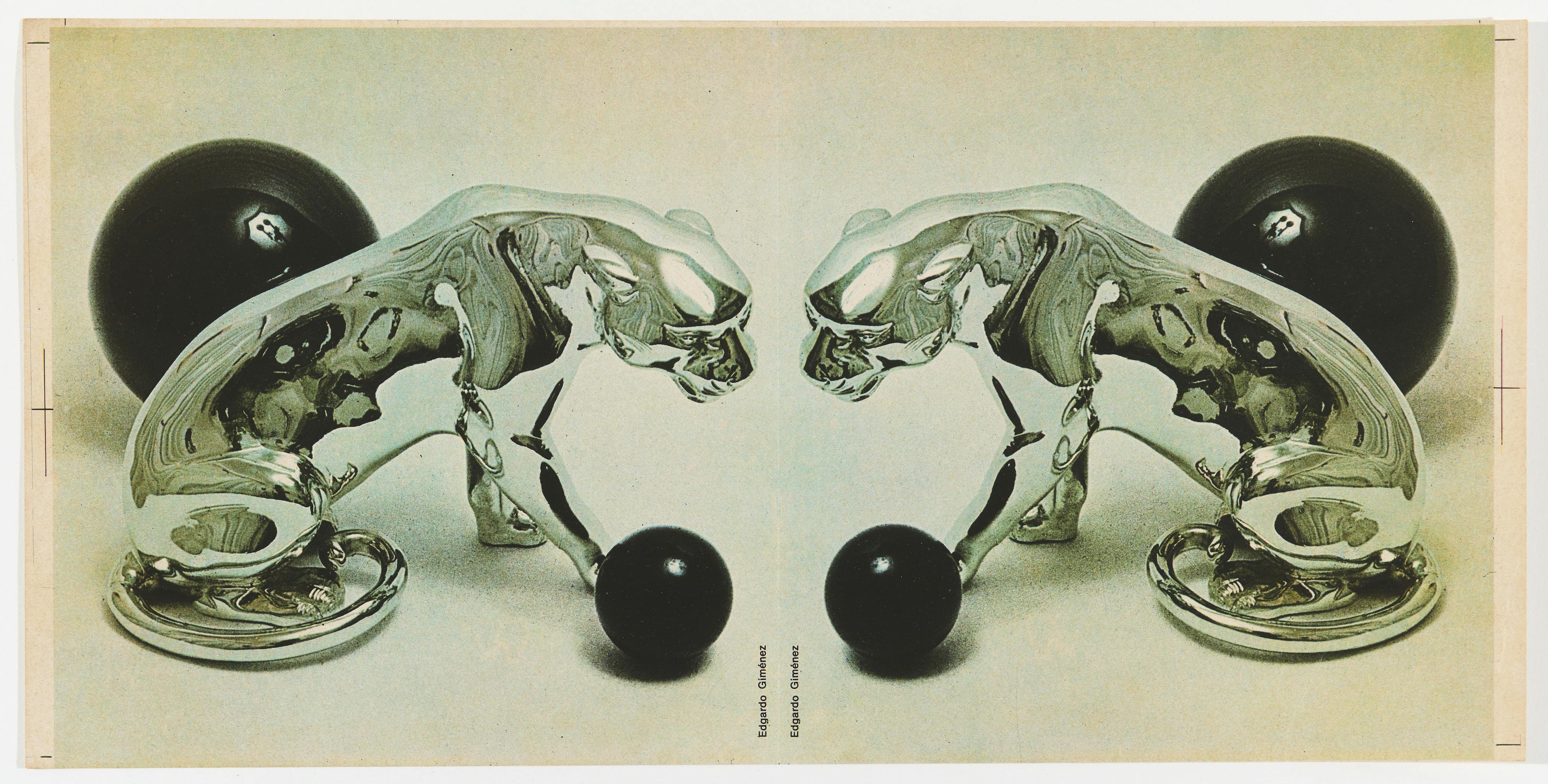

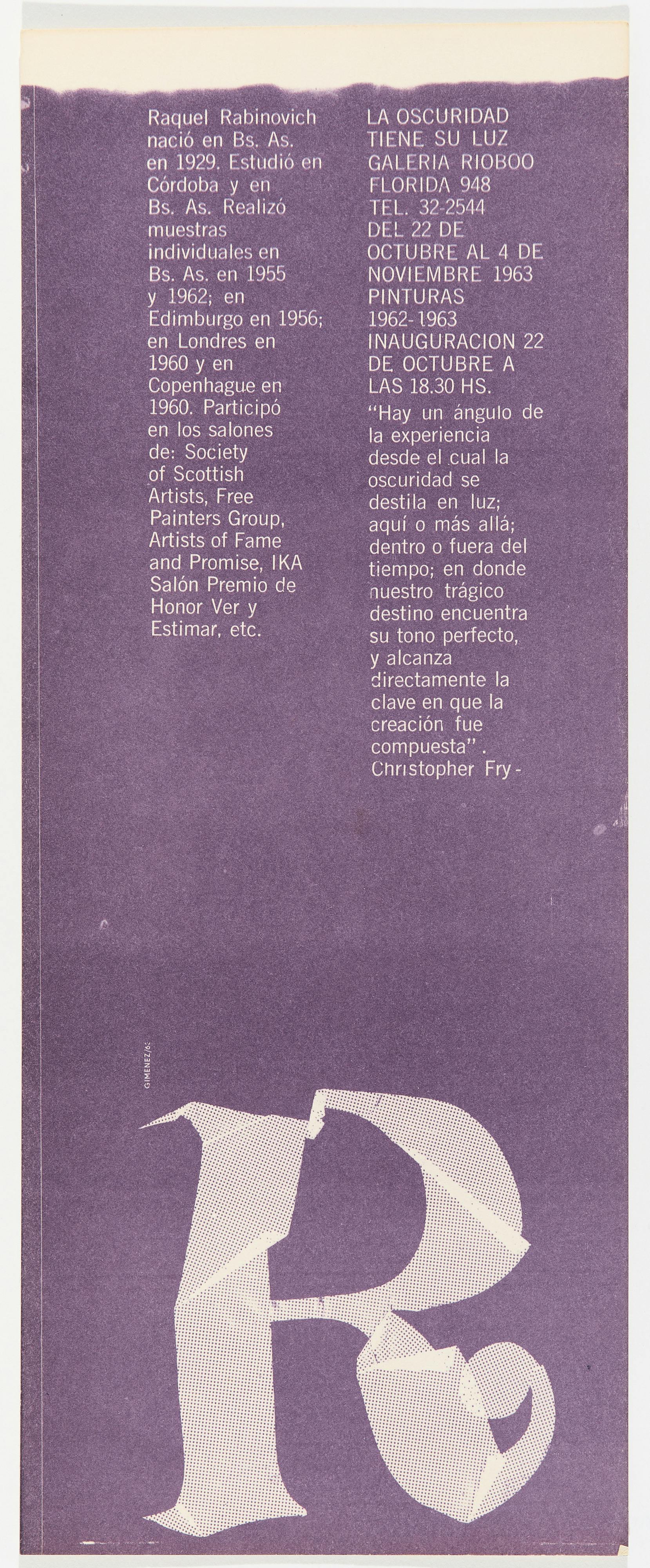

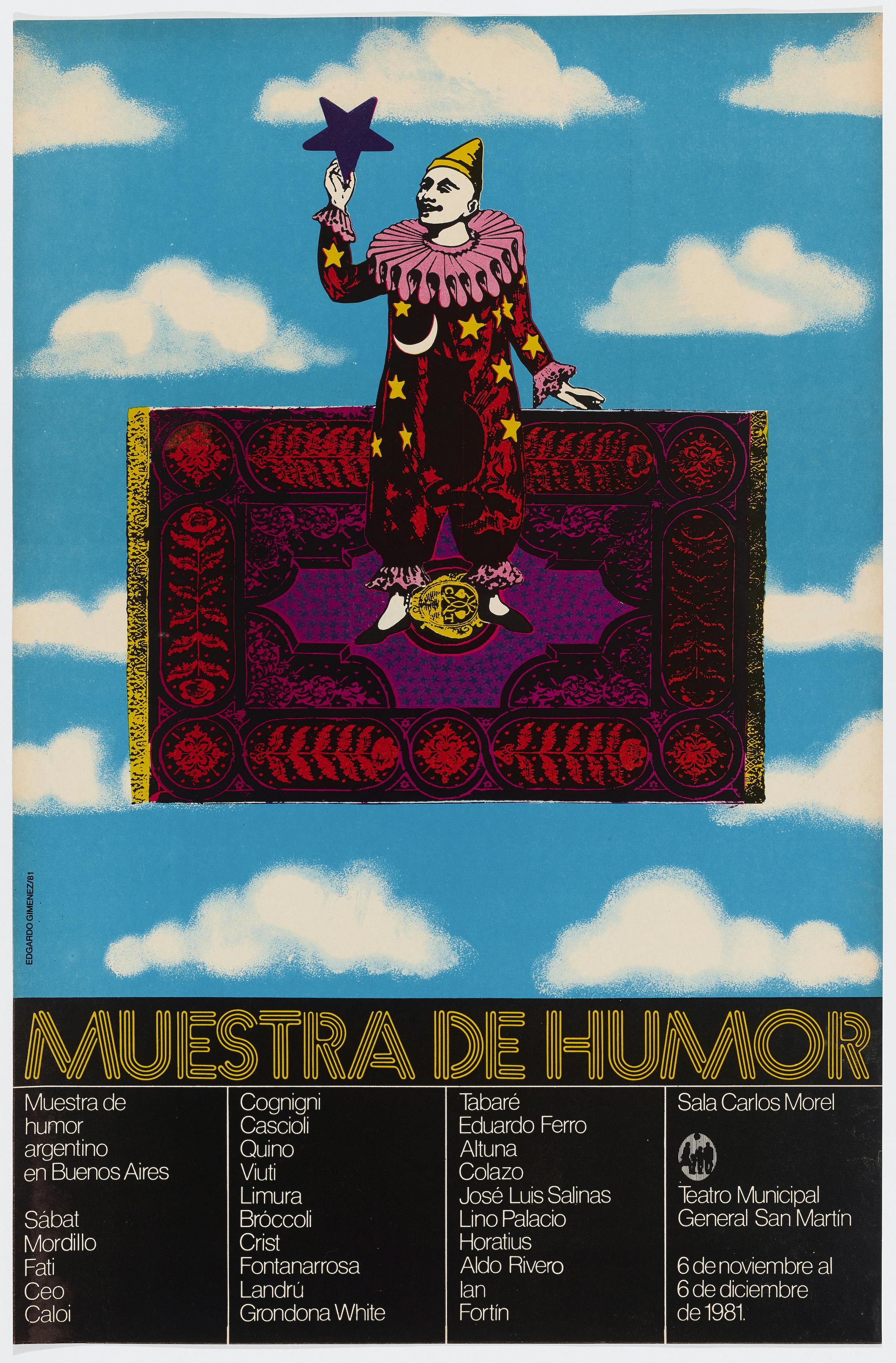

To celebrate the release of Edgardo Giménez: One of a Kind, a publication produced by ISLAA in partnership with Fundación Investigación en Diseño Argentino (IDA) and Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (Malba), the iconic Argentine graphic designer, artist, and architect Edgardo Giménez spoke with Gonzalo Guerrero, a New York–based Chilean designer who is cofounder of the small publisher Secret Riso Club. Giménez and Guerrero—both emerging from backgrounds that encompass industrial design, graphic design, and the visual arts—discussed the Argentine designer’s roots and his work across disciplines.

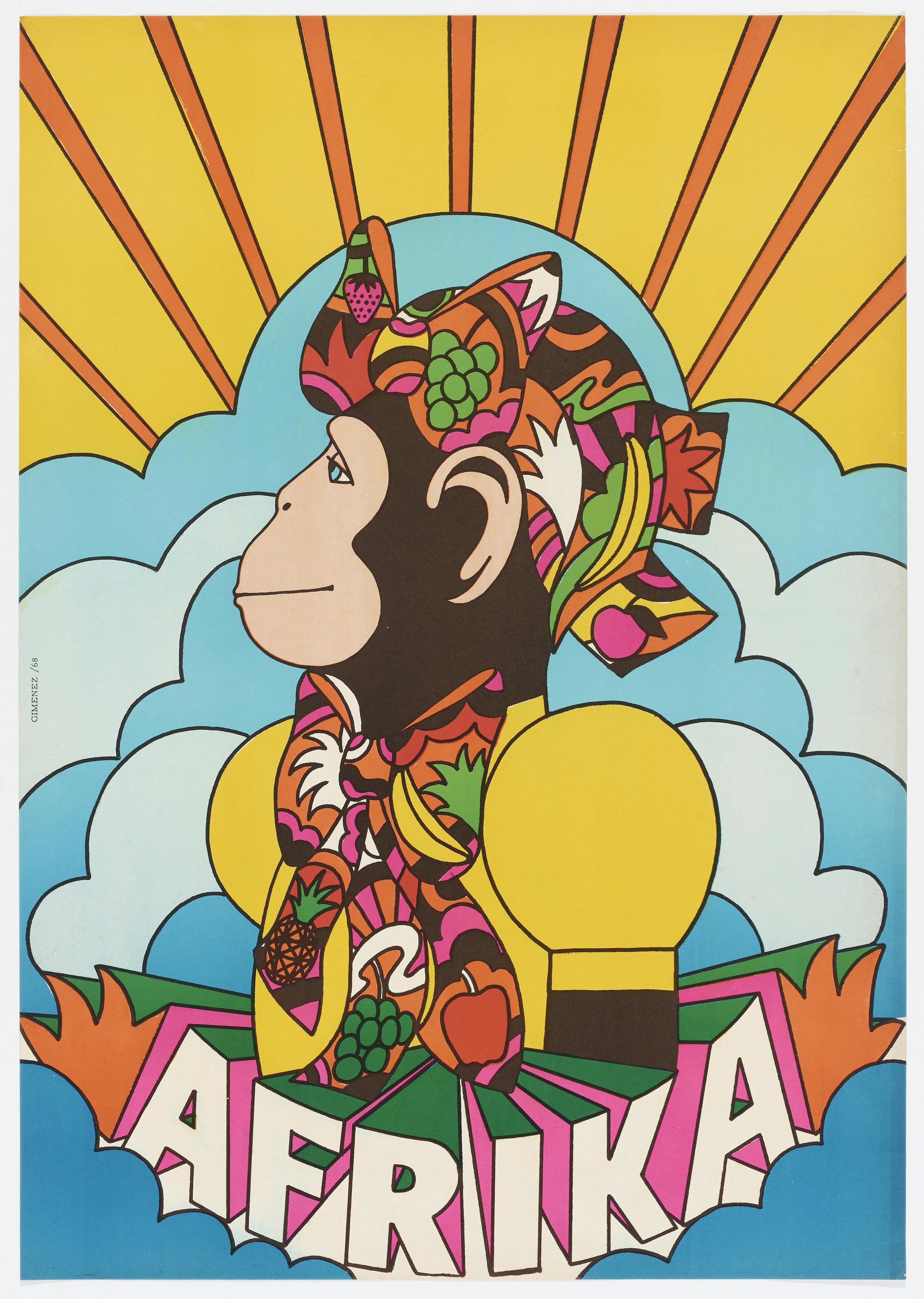

Edgardo Giménez, Poster for the Afrika nightclub in the Hotel Alvear, Buenos Aires, 1968. Offset lithograph, 23 × 16 1/8 in. (58.4 × 41 cm). © the artist. Courtesy the artist and MCMC Galería. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

Gonzalo Guerrero: I would like to start by asking about your beginnings. At what age did you begin working in advertising?

Edgardo Giménez: I was about to turn fourteen. But I had a crucial experience when I was nine. I lived in the neighborhood of Caballito, and on my street corner was a hardware store. When the owner discovered that I could draw, he asked me to work on his shop window. I made a rose bush in the middle of the window with ants made of cardboard with wire legs, which went up and down with pieces of the rose bush. When people walked by, they were struck by it, and they would ask who had made it. And the owner would say: "It was him." So you could say that I was nine when I had my first successful exhibition. What I discovered then was that I liked to please. The prize was people praising what I had done. To me, that was great.

When I was five, I was already drawing, copying Walt Disney characters. He was the entry to a world of fantasy. I think he is a great artist, but he has not been given the recognition he deserves.

GG: I would like to talk about your work during the 1960s. I think it is crucial work, so central to your practice. The works from that period present a very strong symbolism and synthesis that marked your later work, which developed and expanded to different areas. Could you talk more about it?

EG: I began my career as a graphic designer. Which is not far from the path that many American Pop artists took, right? Warhol worked on shop windows, that type of thing, and that paved the way for him to become who he was.

I think that when you have a relationship with advertising, you realize how effective it can be in promoting things, you learn how to make it easier for people who are not related to something to grasp it, because it is shown in a different way. I made a poster that said: "Why are they so cool?" It was on Florida and Viamonte [streets, in Buenos Aires]. That poster increased the number of people who got interested in what [I, Dalila Puzzovio, and Charlie Squirru] were doing. I thought that interest would only last as long as the poster was up (which was about ninety days). But it continued. Now, [that poster] is presented as a landmark on every modern art history book. That surprised me.

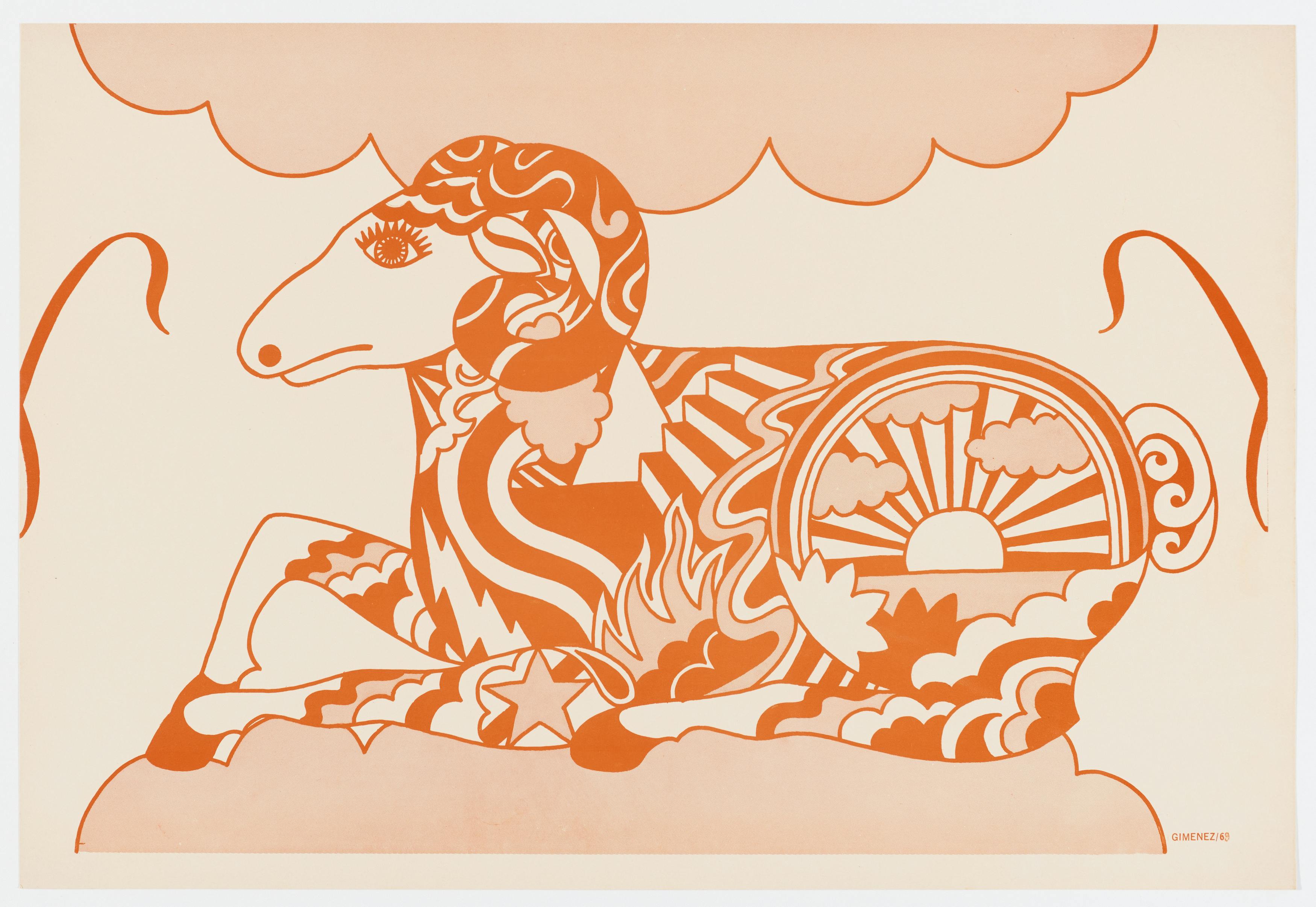

Edgardo Giménez, Untitled (Orange Goat), 1969. Offset lithograph, 13 1/2 × 20 in. (34.3 × 50.8 cm). © the artist. Courtesy the artist and MCMC Galería. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

Edgardo Giménez, Untitled (Cat), 1970. Offset lithograph, 10 1/4 × 9 1/16 in. (26 × 23 cm). © the artist. Courtesy the artist and MCMC Galería. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

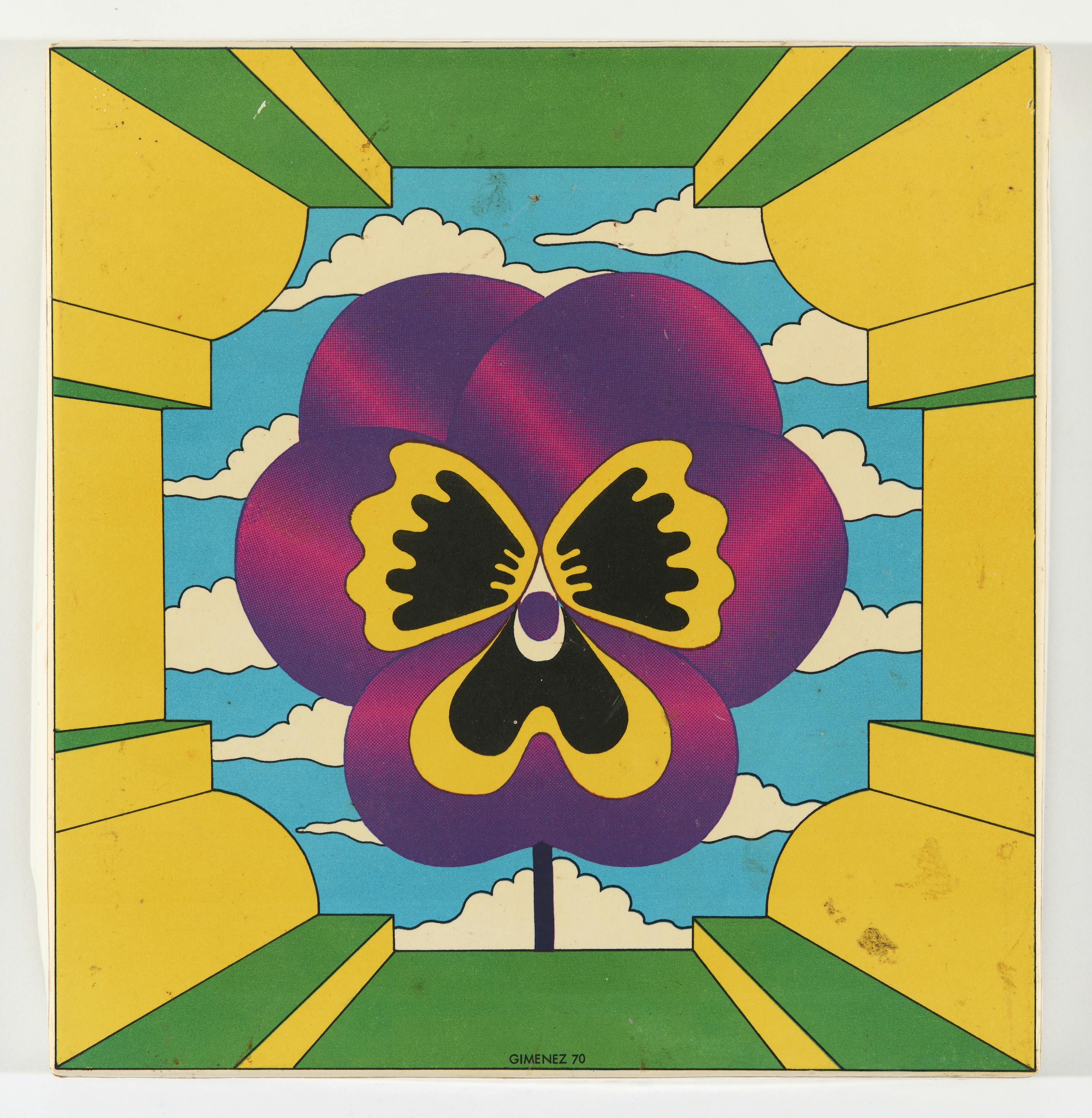

Edgardo Giménez, Fuera de caja box(Flower), 1970. Offset lithograph, 8 1/4 × 8 1/4 in. (21 × 21 cm). © the artist. Courtesy the artist and MCMC Galería. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

I think that when you have a relationship with advertising, you realize how effective it can be in promoting things, you learn how to make it easier for people who are not related to something to grasp it, because it is shown in a different way.

GG: It is interesting how all that graphic work seems to have provided you with a formal aesthetic. I think it was in the 1960s and 1970s that you created your recurring symbols: the panther, the rainbow, the monkey. . .

EG: Now it is clear. In the recent exhibition at Malba [Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires] there are some set designs that I made for cinema, and some works that I made without a predetermined destination, or whose place is given by the people who get enthusiastic about the work, who buy it and install it in their homes. 1

I am self-taught in everything. My first work in architecture, the first house I built, was selected by MoMA for the exhibition Transformations in Modern Architecture (1979). I was the first to be surprised, because I thought: “If I had done fifteen houses, then yes, maybe one came out well, and we can show it.” But it wasn’t like that. Without being an architect, having been self-taught, my work was included in one of the most important architecture exhibitions ever made at the MoMA.

GG: Was that Romero Brest’s house? 2

EG: Romero Brest, yes.

GG: It was during that process, thinking about the conceptual and practical aspects of that project, that you adapted yourself to different industries. It’s like learning about construction. You basically had to make a sketch. It can be about an idea or the concept for a house. . .

EG: I made that first house as a sculpture. I was on the construction site, and would tell everyone: “No, higher. There should be an arch here.” At a certain point, when the house was almost finished, I went out to the park with Romero Brest, and told him: “I think we should have another arch here.” And Jorge said: “No, it’s perfect. Stop overthinking; don’t do it.” I insisted, and he said: “Alright. Indulge yourself. Do it.” We walked through the park again, looking at the house. And he said: “I have to admit you were right.”

You only grow as a person when you are with people who are not prejudiced. With people who are free, and who use their freedom to incorporate different things to their lives, things that have not been approved before. Romero was a specialist in noticing things that were disapproved of, and then legitimizing them.

GG: Now that you mention that process, it seems like total freedom. But also some sort of confidence that comes from within. A visual sensibility.

EG: You don’t even think about it. They tell you that you need to do something, and you do it. And what you do comes out great, and people celebrate it and promote it. That is what happened.

GG: Basically, your work in architecture and set design are part of a larger expanded practice that is ultimately connected, as I see it. And the houses are artworks themselves. Like you said, sculptures.

EG: [Brest] would say, “I don’t live in a house with works of art, I live in a work of art.” Of course, when you work with open-minded people, everything is easier. If I had to repeat my life, I would do it exactly the same. I was never bored. If I always had to do the same thing, I would be extremely bored. Change is crucial. Brest used to say: “Permanent change is the only truth.”

It’s not that I’m comparing myself with anyone, but when I told Brest, “It is strange that they are inviting me to MoMA—I’m not an architect,” he said, “Le Corbusier and [Mies] van der Rohe were not architects either.” They both produced architectural works, but it’s not like they had their diplomas hanging on the wall.

GG: Well, in many disciplines the most interesting things come from artists or people who did not necessarily study that or come from that world. Speaking of which, I am very struck by how you moved from one discipline to another: painting, sculpture, architecture… How was that process for you?

EG: It was a very natural sort of thing, because I possess a great imagination. I was not prepared to do architecture, nor to do graphic design, nor to do anything. It all comes from a person with a strong imagination, someone who puts all their imagination into every new work. I’ve already come a long way with this whole story and things have been going very well.

Creation has to be free. You can’t be trapped by a style or a way of doing things. You don’t have to repeat the same formula to have a personal style, because you’re always looking for things that other people are not looking for. It is about the quest for an original way of communicating with people and nothing more. That is what advertising is. Advertising seeks to show more in order to sell more. It wants everything to be more.

GG: What advice would you give to new generations?

EG: Rather than giving advice, I would say do whatever you want. That is the advice. Do whatever you choose to because you feel like it. That’s where you put your heart.

GG: To do whatever you want.

EG: We don't live for a thousand years. We only live for a little while. So we need to know what we want and do it. Just enjoy it.

GG: Enjoy life.

EG: Enjoy it, exactly.