Cecilia Vicuña, Vaso de leche (Glass of Milk), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Performance in front of the house of Simón Bolivar, Bogotá, as part of the collective action Para no morir de hambre en el arte (To Avoid Starving to Death in Art) at the invitation of CADA. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

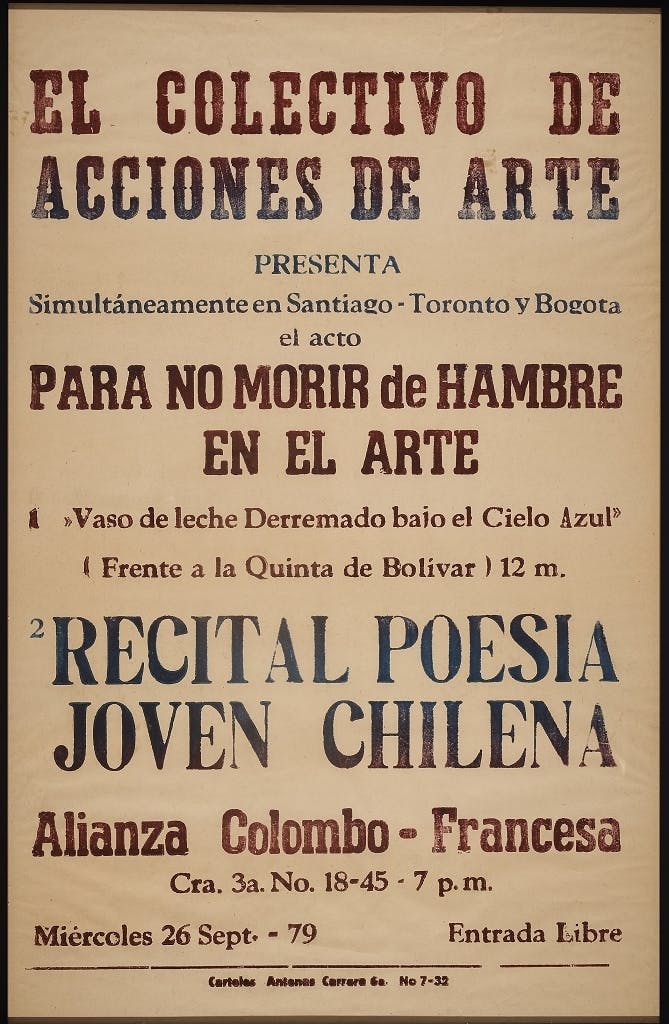

On September 26, 1979, Chilean poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña knocked over a glass of white paint as part of an action by Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA) titled Para no morir de hambre en el arte (To Not Die of Hunger in Art, 1979). The performance was documented in photographs as well as through print ephemera, including a poster announcing the event. In this text, artist Lizania Cruz responds to the different temporalities in which art actions take place and addresses how this work has affected her own practice.

Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

Action-based art exists in two distinct temporalities: the real-time immediacy of the event and the record in which it is captured. During the event, chance, context, and audience participation play a crucial role in the formation of the image. In a January 2021 conversation at the Pratt Institute’s Global South Center, Cecilia Vicuña stated about her performances, “I don’t know what the performance is going to be, because nobody in the audience knows either. So, none of us know. And from the not knowing of all of us, it is as if a weaving of images begins to emerge. 1 By contrast to this lack of control over how the performance itself unfolds, the artist can have a great deal of control over how it is recorded and archived for posterity: after the event, the action is defined and restricted by the register’s frame through photographs, video documentation, printed ephemera, and written or oral descriptions. Through these media, the audience becomes a spectator rather than a participant.

Ever since I started thinking of the sidewalk as a canvas for my actions and of the everyday as a material for art, I’ve been fascinated by Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA). Founded in 1979 by sociologist Fernando Balcells, writer Diamela Eltit, poet Raúl Zurita, and visual artists Lotty Rosenfeld and Juan Castillo, CADA was an artistic activist collective that created dissident actions in response to Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile. Motivated by a desire for sociopolitical change, these happenings touched all aspects of the public sphere. CADA saw the urban landscape as their museum, media and propaganda as dissident weapons, society as a collective of artists, and life itself as a work of art.“ 2

I was born in 1983, just years after CADA’s first international action Para no morir de hambre en el arte (1979). This action took place in three cities simultaneously: Bogotá, Toronto, and Santiago de Chile. The event in Chile was captured in a five minute and forty second video, in which white text on a black background reads, “Milk is distributed in a poor neighborhood. Thirty liters of milk are sealed in an art gallery. A speech is broadcast in front of an international organization. A text about our shortcomings is published in the only opposition magazine.” 3 In this brief synopsis, we are given glimpses of the different encounters facilitated by CADA’s members. The events in Santiago were also described on a minimal white poster, which listed the four locations of the activations in black sans serif text. From these registers of the action—the video and the poster—it is easy to miss what theorist Walter Benjamin describes as the artwork’s “presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” 4 It is from disparate sources that I’ve cobbled together a deeper impression of this work, drawing on descriptions in art books, oral accounts of the Chilean dictatorship and the volatile political climate in South America during the 1970s, and photographs of the action itself.

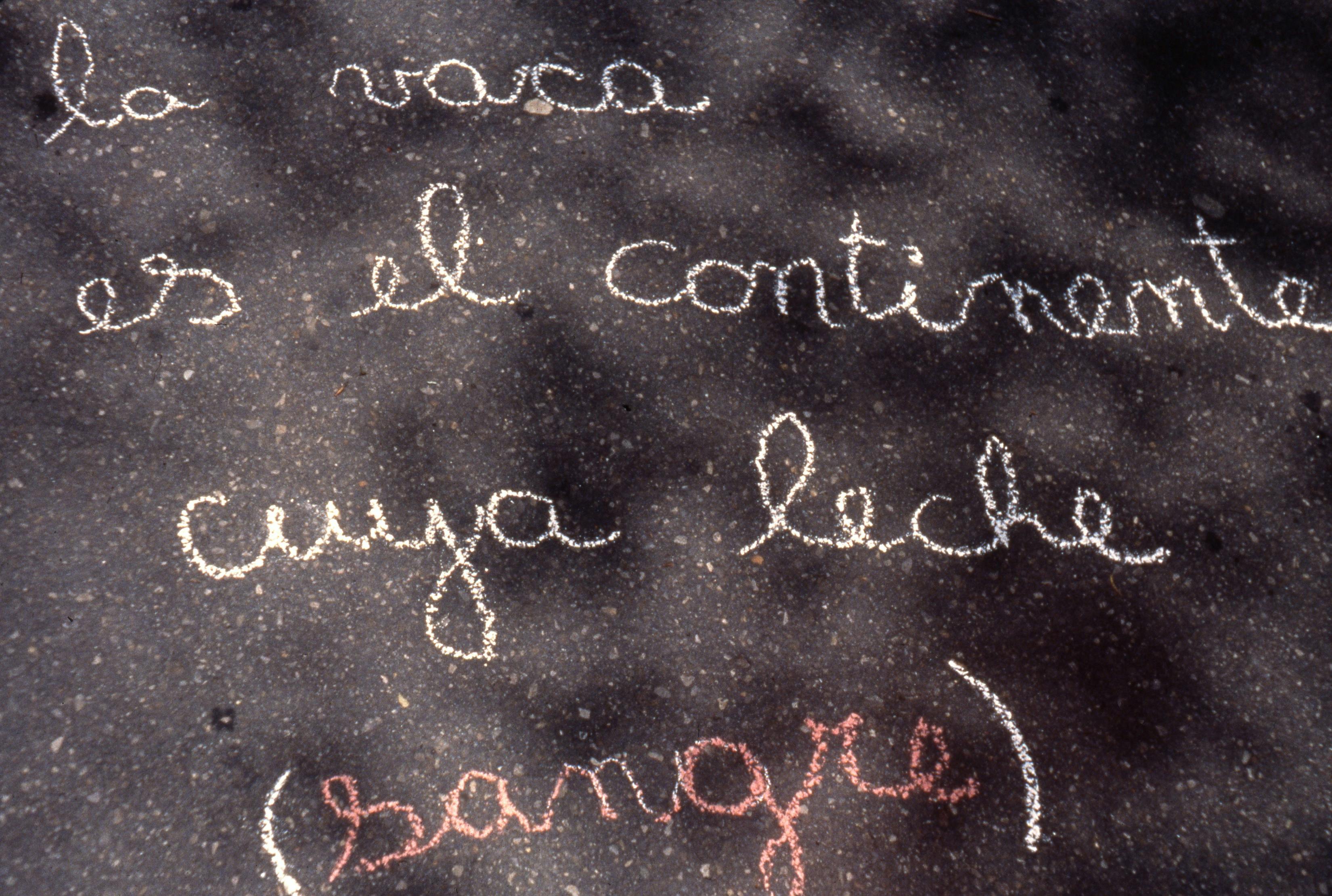

By contrast, I’m satisfied by what is recorded of Vicuña’s contribution to this action in Bogotá—titled Vaso de leche derramado bajo el cielo azul (Glass of Milk Spilled beneath the Blue Sky) in the poster for the event but subsequently known simply as Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá, 1979)—where, pulling on a red thread wrapped around its circumference, she spilled a glass filled with a mixture of water and white paint onto the pavement in front of Simón Bolívar's residence. Vicuña’s flawless use of the poetic to comment on the estimated 1,920 children who died in Bogotá as a result of drinking milk mixed with paint in 1979 5 is exquisitely articulated in the photographs and poster of the action. These materials make me rethink my skepticism toward the register. Because, in this case, the evidence in it conjures what Benjamin would call the aura of what is about to happen and what has passed.

CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte),Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979. Letterpress print, 39 × 25 in. (99 × 63.5 cm). © CADA. Courtesy CADA and 1 Mira Madrid

CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte), poster for Para no morir de hambre en el arte (To Not Die of Hunger in Art), 1979. Printed poster, 21 5/8 × 15 1/8 in. (55 × 38.5 cm). © CADA. Courtesy CADA and 1 Mira Madrid

About to Happen: Announcement

Public announcements such as posters, flyers, and advertisements have long been used by artists to engage everyday citizens and spark dialogue out of the bounds of the art institution. Often these media are printed en masse, in formats such as digital, offset, or letterpress printing. The letterpress was invented in the fifteenth century by Johannes Gutenberg and became one of the first tools for the mass dissemination of ideas. As abolitionist Wendell Phillips said in an 1852 speech on public opinion, “What gunpowder did for war, the printing press has done for the mind. . .” 6 When Phillips referred to the printing press, he was speaking about the letterpress.

It’s no coincidence that CADA and Vicuña employed this production method commonly used for the spread of political discourse in the public sphere. CADA used these tools to enlist a broader public in their antiauthoritarian protest and denounce the institutionalization of Pinochet’s regime. Furthermore, these printed announcements become the first phase of their ephemeral actions; they are a referential index of the event in the register, telling us where, when, and for how long the action will take place.

Vicuña’s poster for Vaso de leche is a letterpress-printed sheet that appropriates the aesthetics of bullfighting posters. The design of this register prepares our subconscious to perceive the action—the overturning of a glass—in a violent light, suggesting that life itself is a battle of life and death.

While the print announces the event to come, it continues to circulate even after the performance. My access to this object is twice removed—what I see is an image of the register, a digital photograph of the letterpress print. There is an aspect of the speculative in looking at the record: we draw conclusions from what we see and what we can’t see at all. All I know is that each letter on Vicuña’s poster is an inky gradient from red to blue—from the color of blood to that of the sky.

I imagine this poster pasted up along the streets of Bogotá. I wonder who saw it and who attended the event. But such a level of detail is not something I can access through the register. The ephemeral is always in debt to the context. That said, what is recorded through the design and production of the poster provides clues as to the intentions of Vicuña’s action.

Cecilia Vicuña,Vaso de leche (Glass of Milk), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Performance in front of the house of Simón Bolivar, Bogotá, as part of the collective action Para no morir de hambre en el arte (To Avoid Starving to Death in Art) at the invitation of CADA. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

Cecilia Vicuña,Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

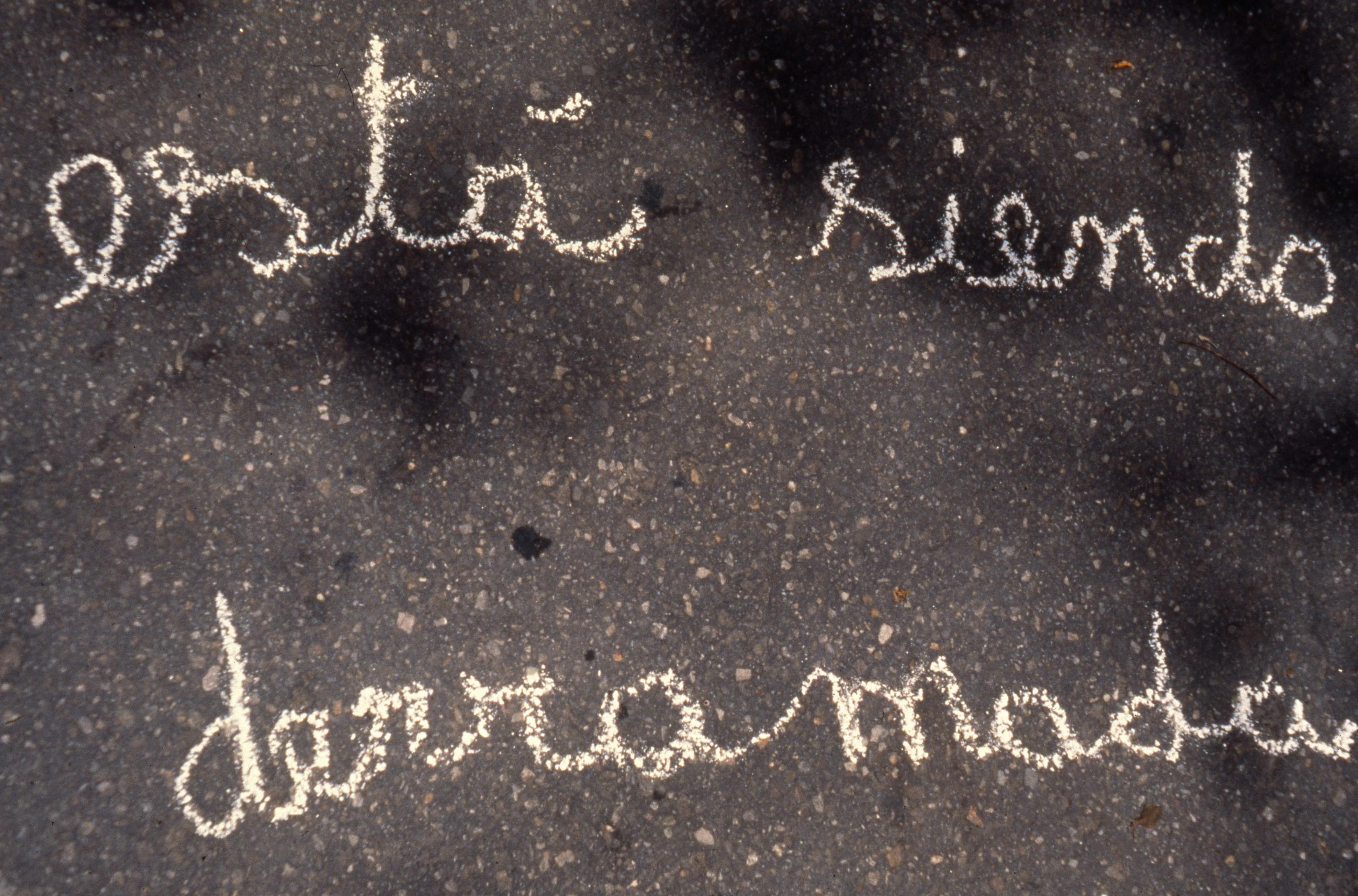

Cecilia Vicuña,Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

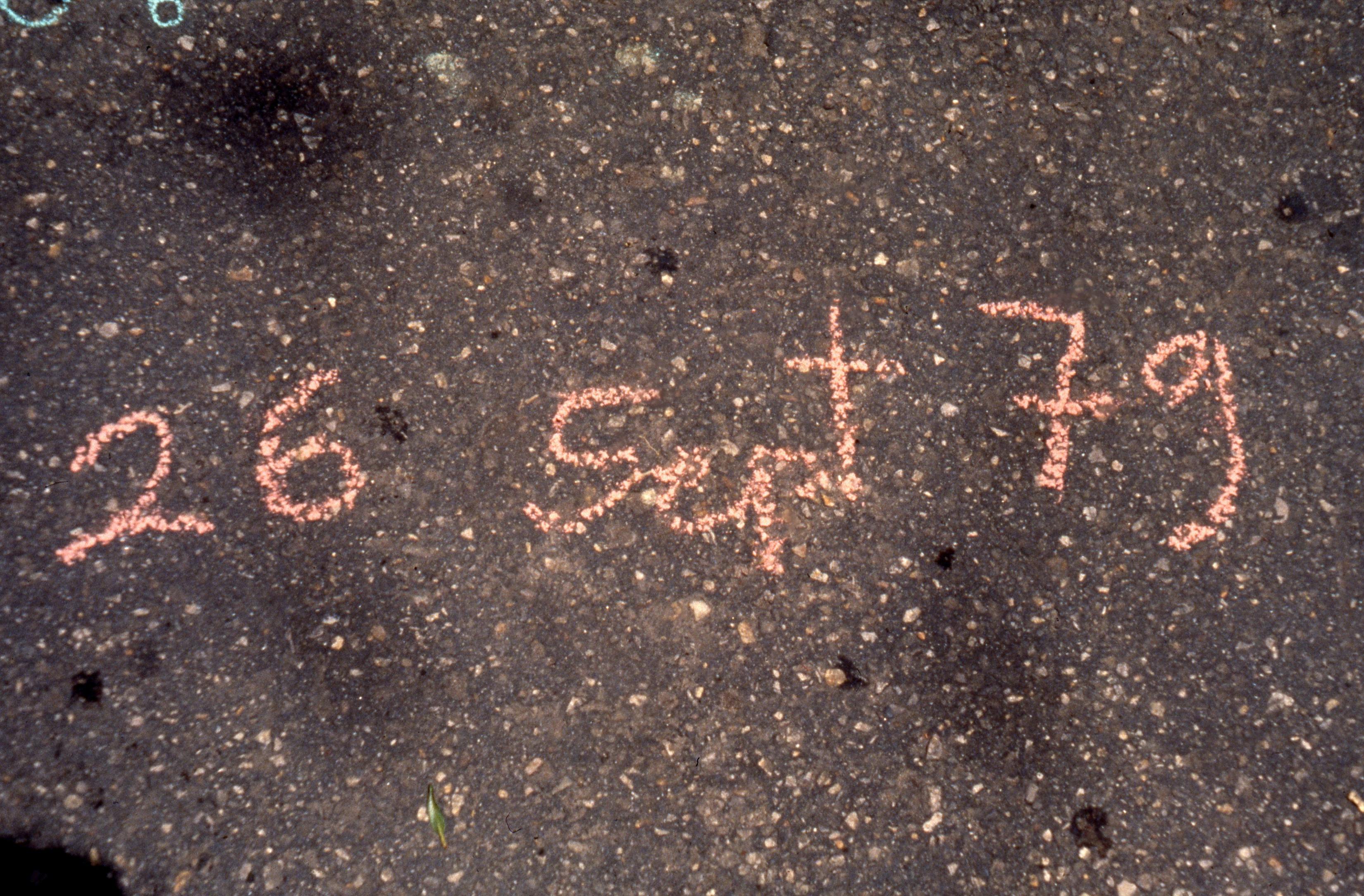

Cecilia Vicuña,Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

What Happened: Documentation

Beyond the poster, eight thirty-five-millimeter photographs are the only documentation that remains of the event. As an audience of the register, I’m drawn to the perfect compositional balance of each image. In the photographs, I can only see Vicuña’s legs and arms. The aesthetics are considered and poetic: the red string, the cursive font, the abstract spill, and the close point of view of the lens, as if it were capturing a crime scene. The way the photographs are sequenced suggests the precise tempo of the event. The harsh shadows turn Vicuña’s disembodied hands and feet ghostly. I’m also enthralled by the expressive mark left on the pavement by the white paint—in what seems like the result of the role of chance in registering the movement. The handwritten letters of Vicuña’s poem are cursive and childlike yet meticulously drawn on the pavement. The word sangre (blood) is emphasized in red, and the prose is deliberately spread across three photographs, allowing us, the audience, to read each word carefully.

Through the photograph, Vicuña asks, “¿Qué estamos haciendo con la vida?” (What are we doing with life?) La vida (life) is an ephemeral and precarious act, which the state—whether democratic or fascist—persistently misunderstands and fails to support.

Decades after Vicuña’s action, we are facing a baby formula shortage in the US as a consequence of a network of phenomena, including labor shortages due to the pandemic, supply chain disruptions, and a product recall prompted by the deaths of nine infants. 7 In the New York metropolitan area, seventy percent of infant formula was out of stock as of May 21, 2022. 8 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced an effort—Operation Fly Formula—to import baby formula from overseas and distribute millions of cans. These measures are expected to ease the shortage by the end of July. 9 Yet, while the population awaits these governmental interventions, parents are still scrambling to find ways to feed their newborns through informal milk swaps, which offer an example of collective action in response to neglect by the state. In the words of one mother, “You’re trying to bond with your baby and do all of the things that mothers feel pressure to do in the beginning. You are sleep deprived. Your hormones are racing through your body. And now you have this fear: ‘How am I going to feed her?” 10

In 1979, Vicuña’s action specifically alluded to former Chilean president Salvador Allende’s socialist policy of providing a half liter of milk to each Chilean child daily as a preventative measure against malnutrition and infant mortality—and put it in direct dialogue with the criminal negligence of a private company, which sold milk mixed with paint and consequently killed thousands of children. Today, the register of Vicuña’s action could also be seen as a criticism of the US government’s failure to address the formula shortage. It has taken more than six months for one of the richest countries in the world to resolve this issue. Although I have written on Vicuña’s Vaso de leche as both a document of an art action and an index of a historical political moment, it is disconcerting how relevant her ideas continue to be to our modern day lives.

Cecilia Vicuña, Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

Cecilia Vicuña,Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

Cecilia Vicuña, Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

Cecilia Vicuña, Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of Milk, Bogotá), 1979, printed 2002. Chromogenic print, 17 1/2 × 22 in. (44.5 × 55.9 cm). Photograph by Óscar Monsalve. Ⓒ and courtesy the artist

Poetry Is Not a Luxury

When I feel disempowered by the institutional lens, I reread a 1985 essay by writer and activist Audre Lorde in which she writes, “For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams towards survival and change, first made into language, then into ideas, then into tangible actions.” 11 Her words are a reminder that poetry allows us to express the kind of future worlds we hope to live in. Poetry itself becomes a written register for liberation.

You can sense this in Vicuña’s practice. She unpacks words’ etymologies to form new meanings, like she does in her project Palabrarmas or in her characterization of her practice as “precario” (precarious). Vicuña’s actions suggest a way of being through poetic thinking. Curator and artist Surpik Angelini writes of Vicuña’s “voice, breath, accent, gestures, signs, traces, and marks” as containing an “aural” dimension. 12 This aurality is palpable in the rhythm and visuals contained by Vicuña’s photographic documentation of Vaso de leche. In a 1982 piece for the New York–based feminist magazine Heresies, founded by a feminist artist collective of which Vicuña was a member, she writes, “I had known from the beginning that Western civilization had done away with poetry as a necessity of life, that poetic thinking was a transgression.” 13 It’s imperative that we transgress not only in the register’s frame but also in the way we live collectively. By bridging the worlds of art and life, Vicuña and her practice provide a model for how we can do that.

For me, poetry is a tool for surviving the everyday. In this world ruled by a patriarchal, capitalist, white supremacist, and imperialist system, poetry is the language that provides a portal for imagining other ways of being and belonging. In my practice, I explore these concepts—being and belonging—through different modes of audience participation. In her work Eman sí pasión / parti sí pasión, 1974, from the series Palabrarmas, Vicuña plays on the word “participación” which means to “share or take part in.” When we participate—take part—we are prompted to experience society as a collective. And through this collectivity we become aware of our shared powers. Perhaps it is this type of collective awareness that often gets lost in the documentation of an event. In the ephemeral records of Vaso de leche—in the poetry and rhythm of the photographs, the invitation of the poster—Vicuña’s distinct gestures and marks provide a portal for imagining other forms of collectivity. Through the register, we become aware of the art action’s significance, then and hereafter.