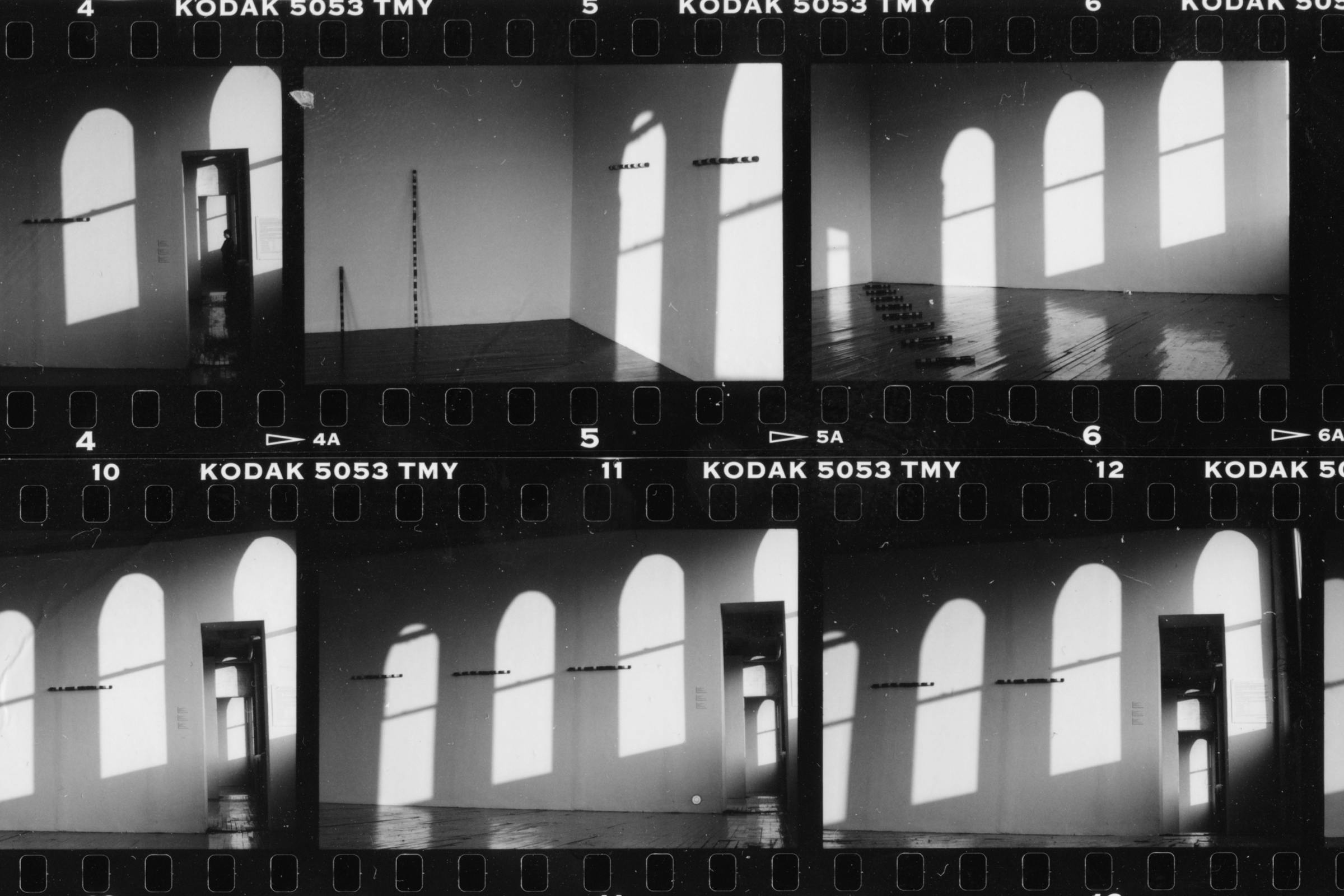

Contact print with photographs taken by David Lamelas in New York, including installation views of André Cadere (1934–1978), P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, 1989. David Lamelas papers, ca. 1960-2018, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers, Succession André Cadere, and Galerie Hervé Bize, Nancy

Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

Translation by Jacob Steinberg.

Alejandro Cesarco: When and how did you meet André Cadere? Was it when you were in Paris or London?

David Lamelas: I met him while living in London, in the late 1960s, which was a rather interesting moment. I had come to London in ’68 as a graduate student in the Sculpture Department of Saint Martin’s School of Art. I was suddenly a student again, something that was very good for me—I needed a little education. [laughs] I had professors like Barry Flanagan, John Latham, and other English Conceptual artists. Through them, and through Saint Martin’s, I had a lot of contact with the new English avant-garde movement, which was the birth of Conceptual art there.

Then I became connected with the Nigel Greenwood Gallery, which exhibited that more Conceptual tendency. Gilbert and George were also studying at Saint Martin’s at the time. That group of people became my friends, and they immediately included me in meetings happening every Thursday at John Latham’s house, where we would talk and debate art. As a new arrival, I had access to that generation, even though they were all older than me. I was the youngest, or the same age as Gilbert and George. And well, in that London environment, I slowly got to know Cadere. At openings, meetings, meals... he seemed to be everywhere. He had quite an active presence and was a quite enjoyable and social person. Cadere was always walking around with his round, painted wooden bars of different colors and sizes. He always attended openings, and at that time, we had a very active social life, in the galleries, the museums... And even though he often wasn’t invited, he was always there, carrying his wooden bars around and talking with everybody. He never spoke directly about the bars, but they always caught my attention. One day I asked him about them, what they were, and he told me it was his work.

He had recently come to London from Romania. I think he lived in Paris later on, but at that time he was in London. Marcel Broodthaers also lived in London then. Thanks to Barbara Rose, who organized small events, Conceptual artists from other countries were constantly passing through London. That was how I met John Baldessari, for example.

Cadere was always hanging around, always among us, coming and going, and always with his trademark bar by his side. Though sometimes he’d place it in a corner. He was a very social person. He spoke with me a lot—he spoke with everyone a lot. I think his father was a diplomat, and Cadere was a rather polite, cultured, refined person. Everybody knew him. Jack Wendler, the American gallerist and collector, held meetings practically every week where Cadere would show up, whether he was invited or not. He would come with his bar and leave it around somewhere. A funny anecdote is that one day during a meal with Daniel Buren—and Buren was very much against the newcomer, since he saw ties to his own work—he apparently, without anybody noticing, hid one of Cadere’s bars in the closet. [laughs] It’s very funny. I didn’t see him do this, but it was talked about later. What I do know is that Daniel, a great friend of mine, was bothered by Cadere’s work.

AC: Did it make him a little jealous?

DL: Do you see connections there?

AC: Maybe a formal connection... but not even that really. No, to be honest I don’t see much of a connection.

DL: In the 1960s Buren wore those striped signs, and he also took to the streets of Paris, remember?

AC: Sure, but that was pretty different, no? That was perhaps more related to social protest, and not so much an insider artworld thing...

Contact print with photographs taken by David Lamelas in New York, including installation views of André Cadere (1934–1978), P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, 1989. David Lamelas papers, ca. 1960-2018, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers, Succession André Cadere, and Galerie Hervé Bize, Nancy

DL: Of course, of course. Precisely. Anyway, it’s just a funny anecdote. We laughed about it later on. Truthfully, Cadere had his supporters in London—the curators Lynda Morris and Barry Barker, for instance—who I think even gave him a show or small event at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. He was very protected in London, and I think his work evolved a lot in those years. He managed to integrate quite nicely with the era, because before that he made a completely different kind of work.

AC: So what you remember most about him is the social aspect of the work, not so much its sculptural qualities? Or rather, what you recall most are Cadere’s interventions, his appearances?

DL: No, no, his appearances were inseparable from that bar. That bar was always with him; he showed up with that bar-sculpture and instead of “exhibiting” it, he carried it around with him—that was the novelty! So, it was a little, let’s call it, life-art. Somehow there was a connection, perhaps somewhat distant, with Alberto Greco, the Argentine artist.

AC: Yes, yes, Ariel [Aisiks, president and founder of ISLAA,] mentioned that you had made that connection, and I found it interesting. I don’t know if you want to add anything with regards to that.

DL: Sure. Ask me a question, please.

AC: I imagine you’re referring to Vivo-Dito more than anything else, or...

DL: To Vivo-Dito, of course, and also to Greco’s attitude of walking around the world making art with ephemeral things. More than anything, I connect it with his attitude. I met Greco here in Buenos Aires in 1964, and truthfully, at that time, what interested me about Greco was the more abstract aspect of the work, the part where he seemingly didn’t do anything, the more Duchampian part, more...

AC: Yes, more to do with signaling. Signaling or framing something, which is an almost proto-Conceptual gesture.

DL: Yes, but in Greco’s case, his being, his attitude was the interesting bit. In that sense he was related, somehow, with what Gilbert and George would do later on. They said, “We are art.” I think Cadere had something of that as well, and that seemed like the interesting part of his work to me.

Contact print with photographs taken by David Lamelas in New York, including installation views of André Cadere (1934–1978), P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, 1989. David Lamelas papers, ca. 1960-2018, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers, Succession André Cadere, and Galerie Hervé Bize, Nancy

AC: Do you see any connection or relationship between Cadere’s work and your own?

DL: Yes, I see a connection between us in that we shared that era and also the use of signaling, which you were describing, and which I practiced as well, in a more spatial way. For example, in the park in London: a tree, a chair, a lamp [Signaling of Three Objects, 1968]. This was clearly about signaling, of course. Or the work I did for Garden Project, Christ Church, Oxford, at the invitation of Charles Harrison, where I gave false information about the city of Oxford. Those three texts for Oxford were the first thing I did when I got to England. Later on came the film A Study of Relationships between Inner and Outer Space.

AC: That was in 1969, right?

DL: Yes, you’re right... But they’re the things that happened while I was in the Sculpture Department at Saint Martin’s. I remember also that one day Anthony Caro, who was my main tutor, told me, “Mr. Lamelas, I never see you at the studio—what is it that you are doing?” And I told him, “Mr. Caro, I am making a film. That’s why I am at the library most of the time.” And he answered, “Well, Mr. Lamelas, this is the Sculpture Department. I suggest you do sculpture.” And thanks to that—a very good bit of advice—I ended up doing Signaling of Three Objects. Which, of course, was a sculpture. It had rectangular steel plates, but they were used for signaling.

AC: Yes, sort of as if you had drawn with dotted lines in space.

DL: Exactly. There were about twenty-eight plates of the same size, steel, thin, painted white, and set up the way architects signal an area. That was the idea. In that sense there is a connection with Cadere, which was also a connection with that era, of course. Somehow Buren also did it in his own way with those stripes. Although, I don’t understand why Daniel was bothered by this newcomer.

AC: And what about your series London Friends? Do you see it as something that could be related to Cadere’s work—the idea of community, belonging—or not so much?

DL: Well, that could be... Yes, it could be... And with Greco too, of course—the social aspect, the documentation... In my case, the documentation comes from a different reference, but the interest in the social aspect was part of the process, yes... You know, when I left Argentina, I left Buenos Aires and came to live in London, I needed to make my space, to find my group of people. So, somehow, when I did Signaling of Three Objects, it was to say, “This is my space.” I now see it like that: this is my space. In one of the photos, I’m even sitting within that space, which was my space in London. The most important thing was that the sculpture was signaling my space. And the act of photographing all my friends [in London Friends] was also a way of telling the world “I belong here,” or “I’m at the center of this group.” I think in the latter case it had to do with a lack of identity. At that young age I think I still didn’t have a very defined, well-constructed identity, you understand? So, I forced it a bit in London.

Contact print with photographs taken by David Lamelas in New York, including installation views of André Cadere (1934–1978), P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, 1989. David Lamelas papers, ca. 1960-2018, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers, Succession André Cadere, and Galerie Hervé Bize, Nancy

AC: Of course, I understand... Let’s leap ahead a few years and talk about the contact print, the series of photos you took in New York at PS1 in 1989.

DL: Well, in the late 1980s I moved from Los Angeles to New York, and when I saw the retrospective of Cadere’s work at PS1, I was quite interested. I went with a camera and captured the material you’ve seen.

AC: Do you remember anything in particular about that show?

DL: Yes, I liked it a lot. I thought the use of space was very interesting. Of course, Cadere wasn’t alive anymore, but it was a very good installation of his work.

AC: Around that time, you were also showing in New York, at Willoughby Sharp’s gallery, right?

DL: Yes, I had become friends with Willoughby Sharp, a quite eccentric character, and he had a gallery on Spring Street. An eccentric gallery, just like him, a kind of underground gallery within the system. And well, he invited me. We got along well. And yes, I had a show at Willoughby’s place.

AC: The show was called Inner and Outer, I think…

DL: Yes, that’s right, it was Inner and Outer. The show was basically large drawings—colorful drawings over blank canvas, some on paper. There was also a small glass installation in a corner. I mean, for me all of that was somehow a way of reconnecting with “art.” Because in Los Angeles I had grown a bit apart from that world; I was doing primarily video works. And once I was in New York, I had to relearn what had been my work in the sixties and seventies, because in some way, or in many ways, I lost my head in Los Angeles.

AC: Well, David, I’m sure we could continue for a while longer, but it’s getting late and we should really get dinner. I don’t know if you’d like to share another anecdote or memory of Cadere, or maybe say something more about his show at PS1, or elaborate on your idea of relating Cadere to Greco...

DL: No, I think it’s good as is. Let’s go eat.