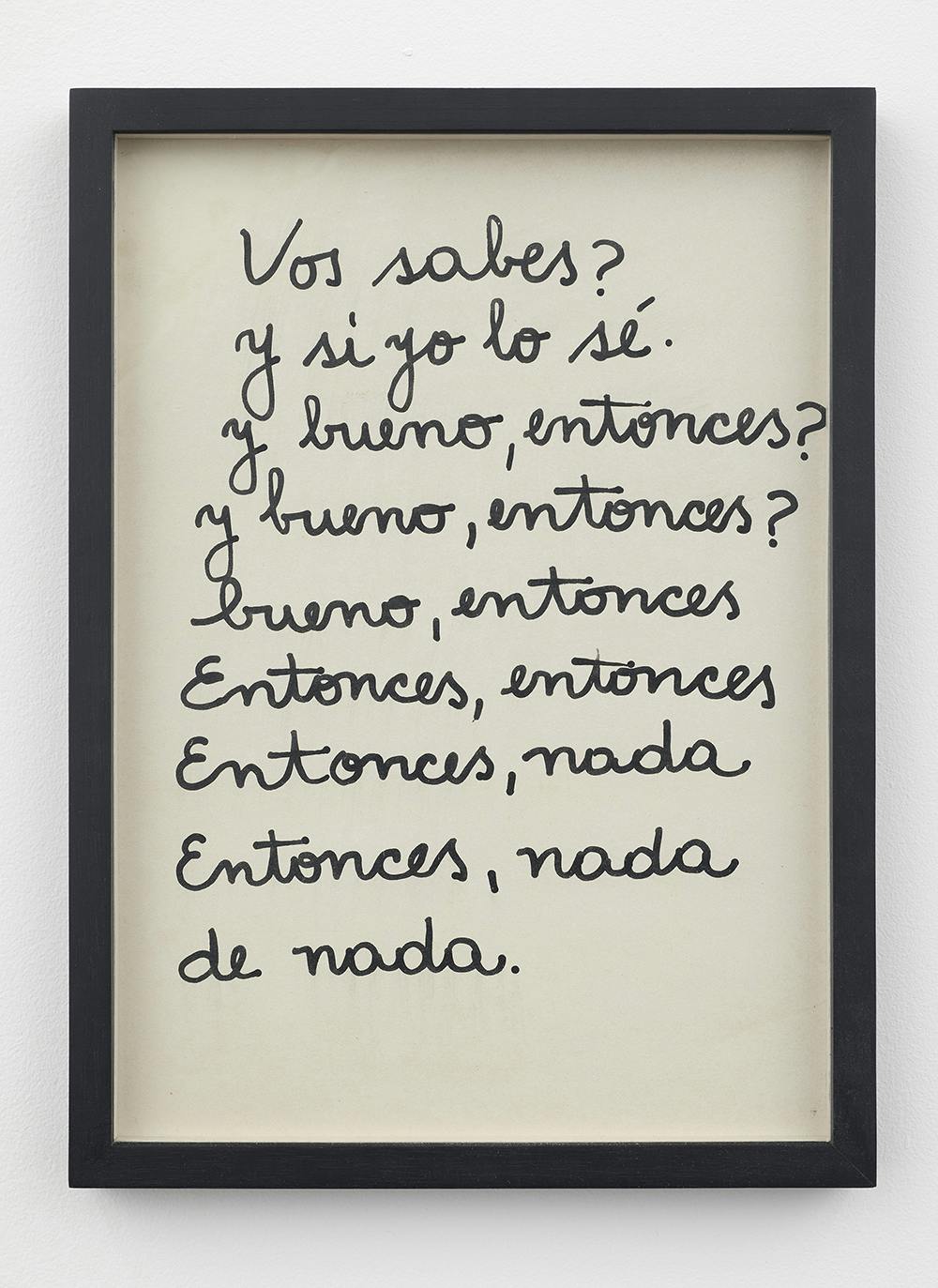

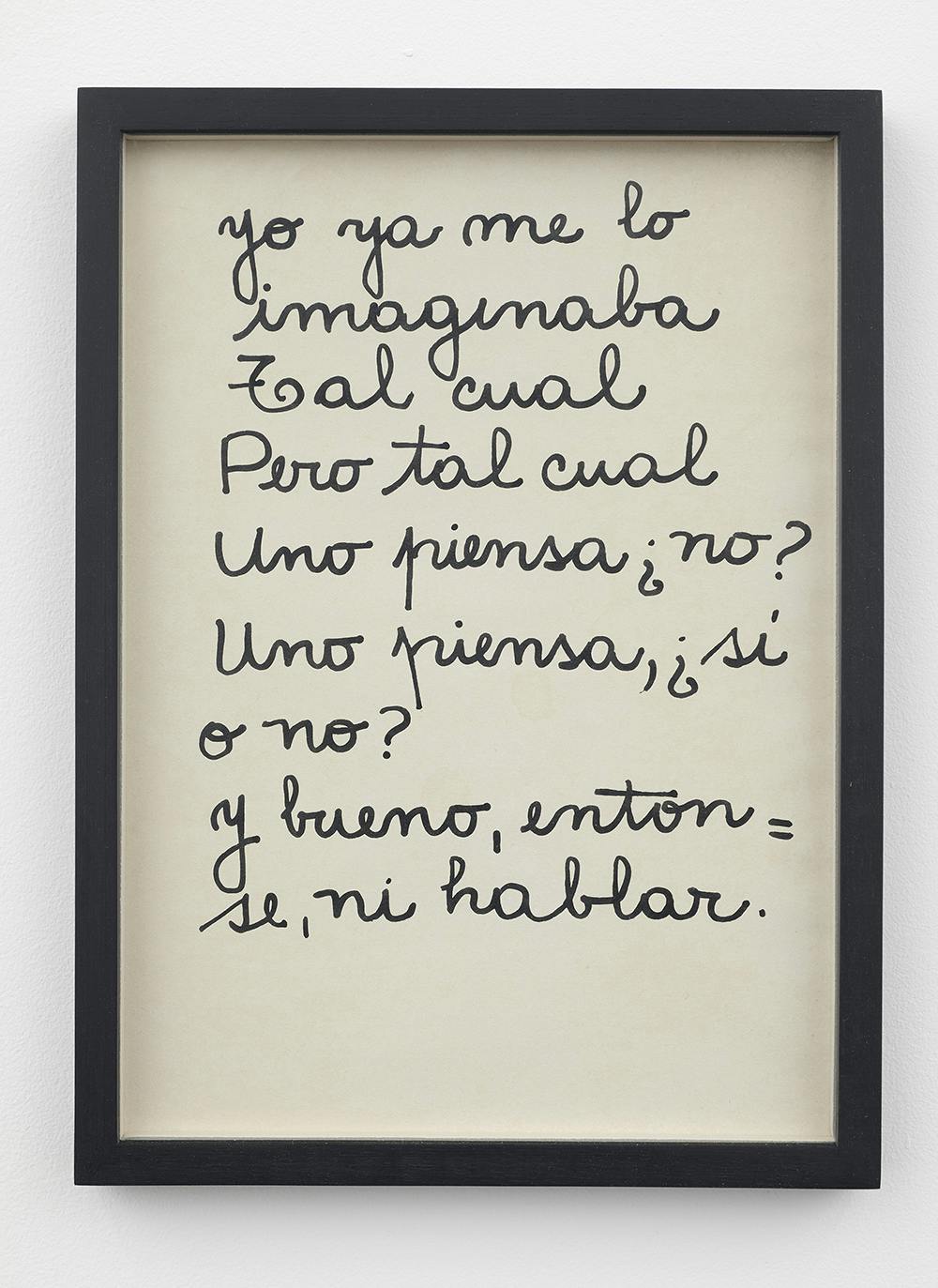

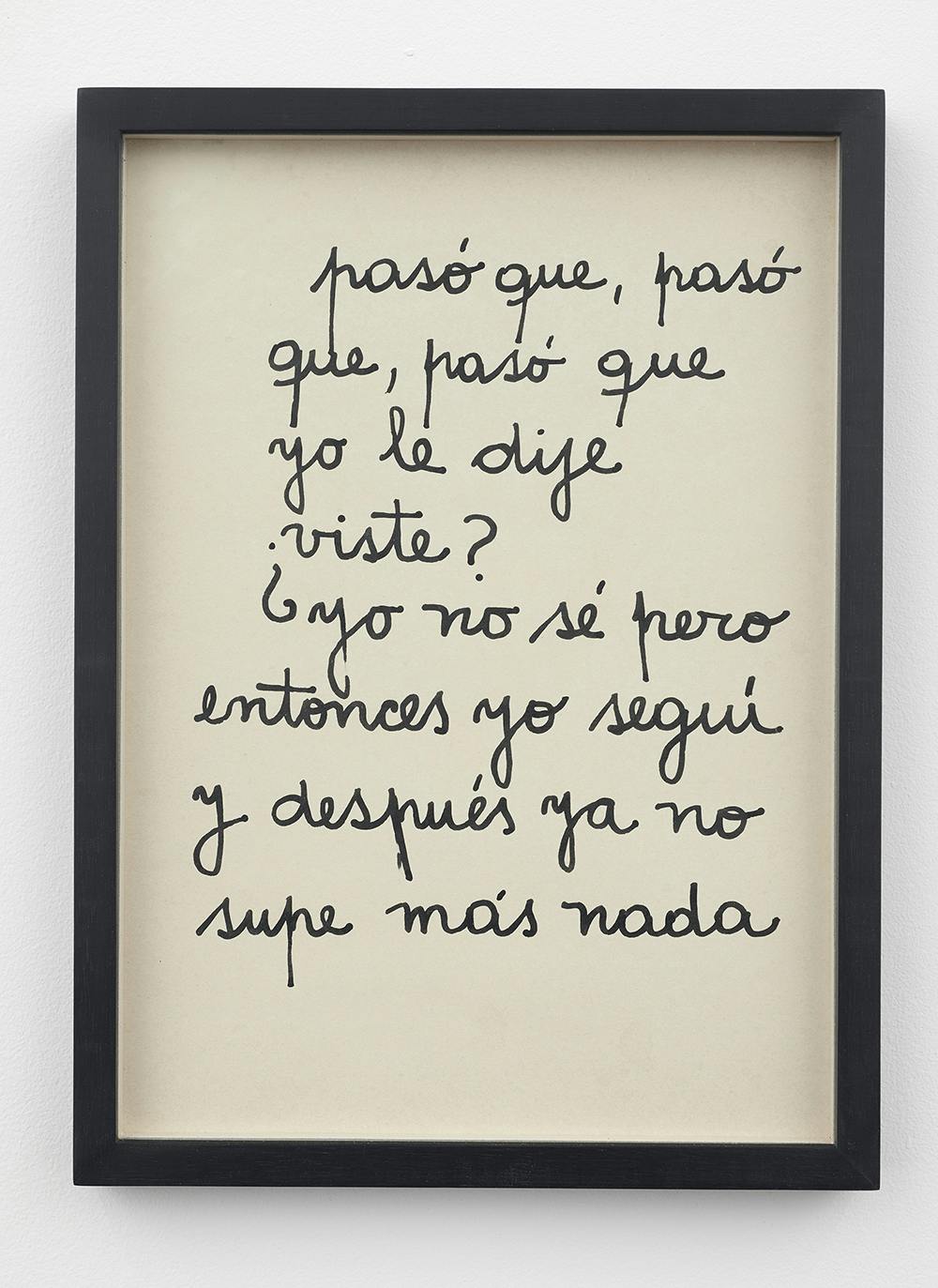

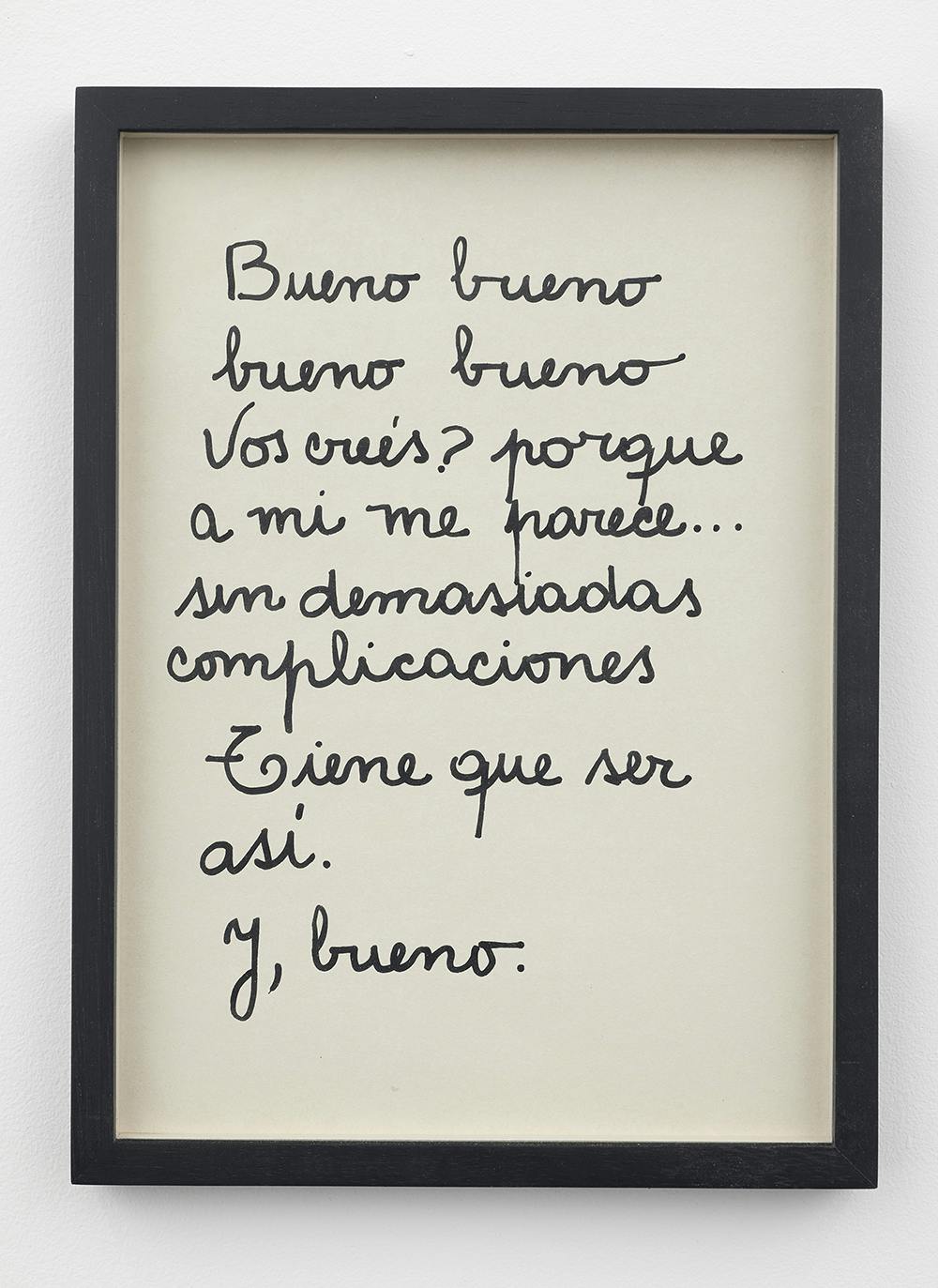

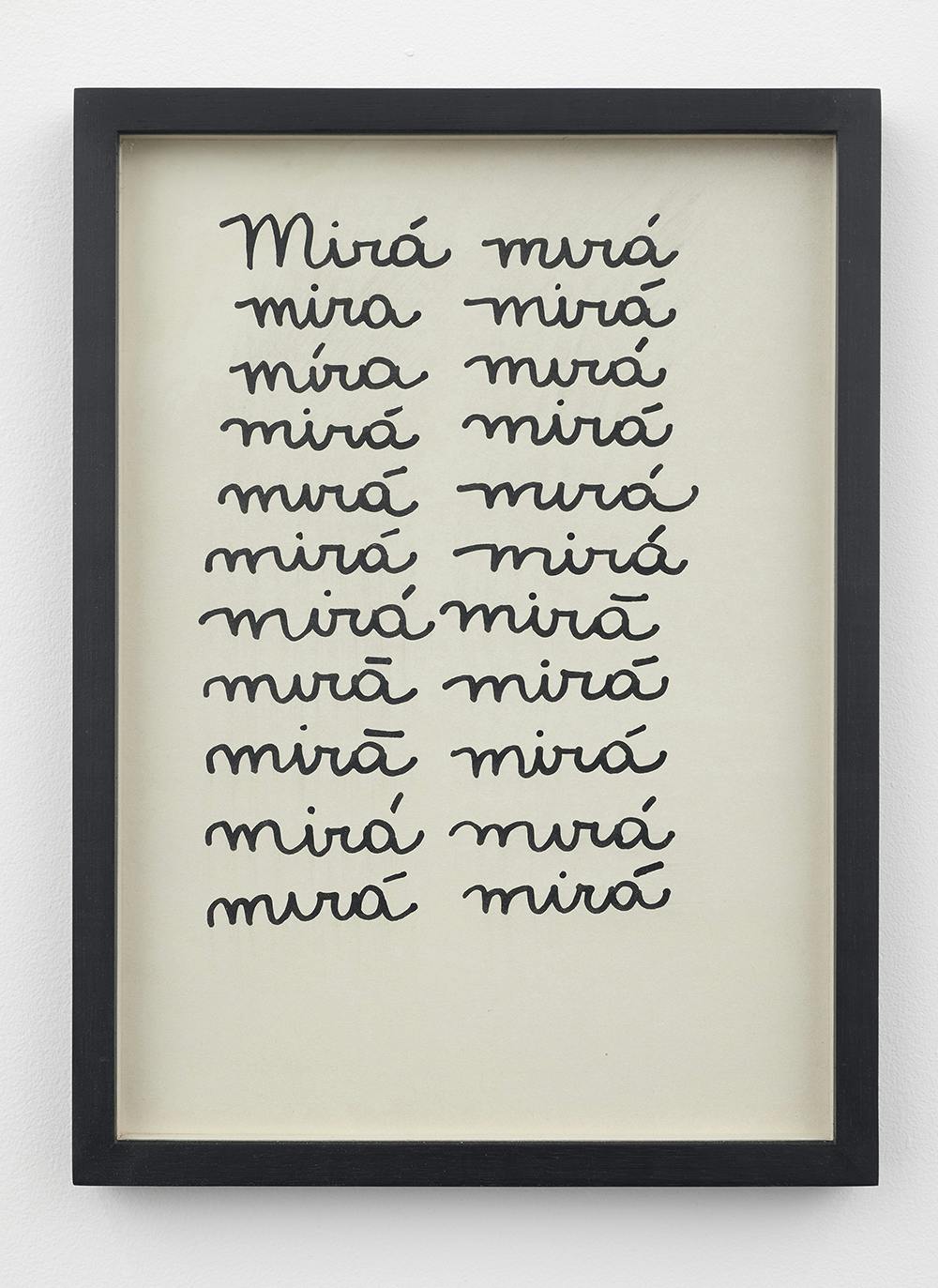

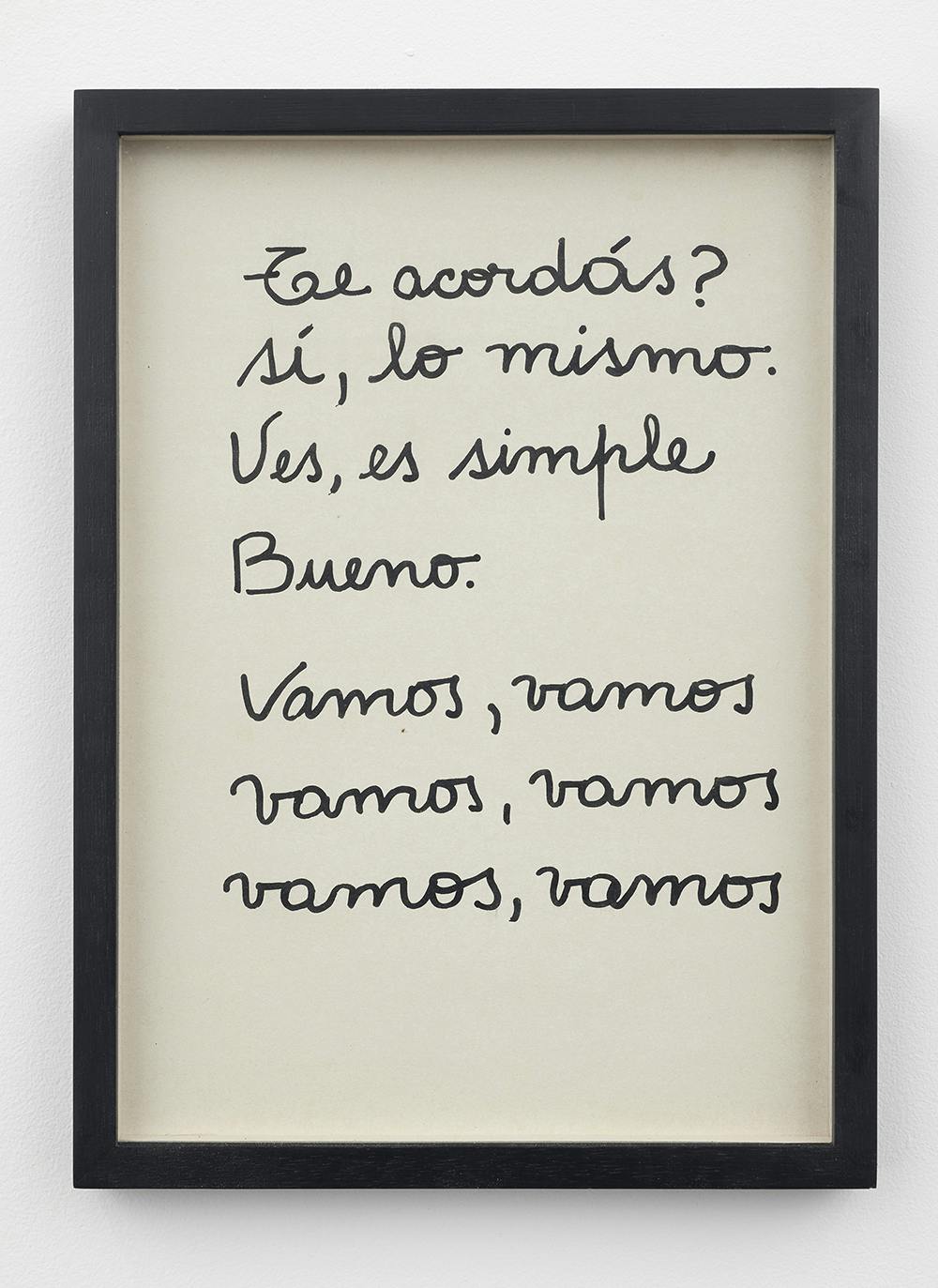

Any time of day, any moment of your life (for all of life is like a single day), if you have ever grabbed a pencil and written your name or the name of someone you know on a sheet of paper, you may have wondered about the origin of that rather strange mechanism we call writing. During different eras of my life (for life is made of eras), I’ve been amazed by the existence of simple letters. At five years old, they first appeared before me, on the Coca-Cola street signs they had in my city. My first memory of writing comes from ads. I learned to read with the logo of an international beverage. Later came school, where we would draw little ducks and chairs. Writing is like drawing. (The other day, a student in my writing workshop read that phrase, and I told her I would steal it from her and here I am doing it.) Those little ducks, chairs, and pine trees were preparation for the grand moment that came halfway into the school-year: mastery of the Latin alphabet. What a great gift that alphabet is! And what a joy to receive it at such a young age! We take it for granted, and then it becomes invisible, natural, and gratuitous. But is there any greater gift than an alphabet? By giving me the Latin alphabet, the society I lived in gave me the blessing of being able to write my name. Thousands of years amassed in the perfection of grapheme technology so I could write “Cecilia” over and over. “Cecilia,” “Cecilia,” “Cecilia,” over and over—the joy of identity.

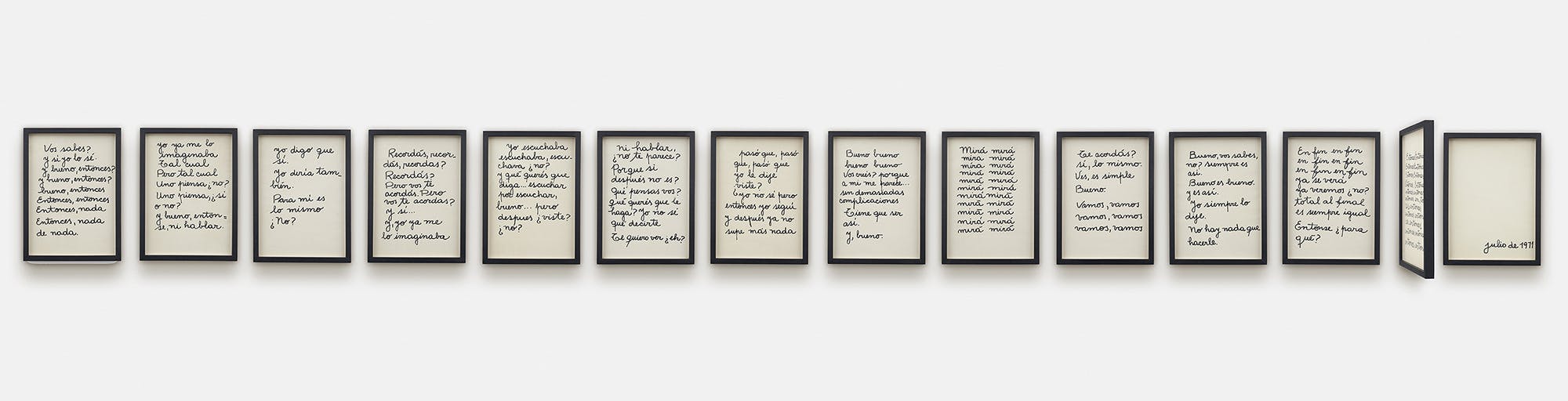

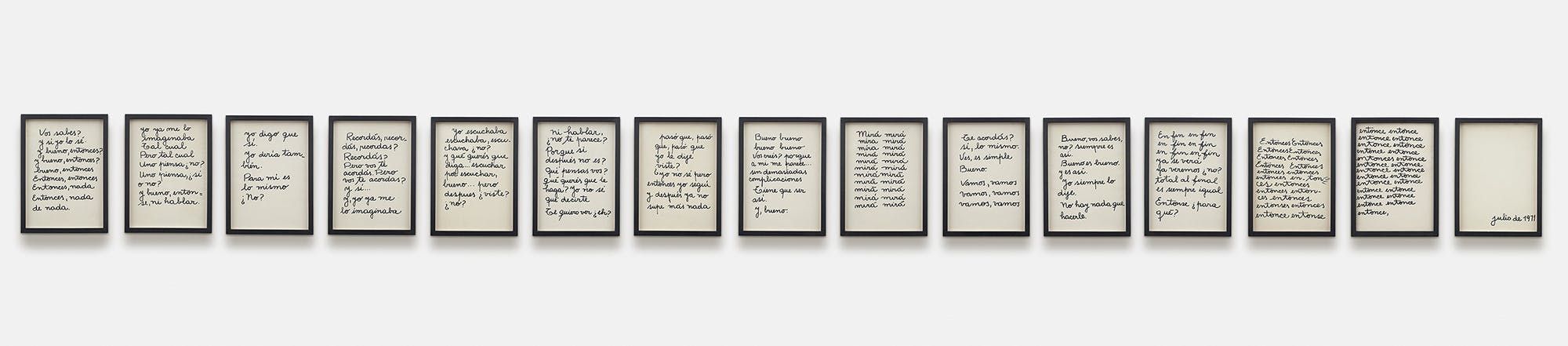

My whole childhood and early adolescence, I practiced my signature. I improved it and polished it off, and one time, at fifteen, a graphologist friend of my mother (she worked in a company’s HR department) interpreted my signature, saying I would be happy. It was the first time she spoke of happiness because she was usually always talking about efficiency. It didn’t matter if I had the signature of an organized, efficient person or not, because my handwriting spoke of a happy personality. Is handwriting happiness? Around that age, around the time of the graphologist’s prediction, I began writing “poems”: always by hand, in notebooks or on sheets of paper, tens of poems, thousands. I say poems in scare quotes because to be honest I didn’t know what they were. I was in love with my writing, and the practice of opening my notebook was just an excuse to contemplate the irregular geometry of the strokes. In the book I am reading this June morning, they quote Susan Sontag: “All great art contains at its center contemplation, a dynamic contemplation.” For me writing was always contemplation, contemplating myself writing. I am reading while sitting in a little bar with raffia chairs across from Plaza de Mayo. At my side I have a lined, soft cover notebook I always carry with me when I go around the city and end up sitting down in some café. It is my eternal notebook for writing by hand. It is the only ritual I’ve maintained since childhood. (Life is a notebook written by hand. Life is many notebooks written by hand.)