Since the 1970s, Mexican artist Mónica Mayer has worked in participatory formats that create platforms for dialogue, debate, and enfranchisement of otherwise voiceless communities. In Mayer’s hands the archive has become an emancipatory conduit for communication, enabling communities to affirm their identities and to challenge daily violences. Excavating Mayer's networked practice, curator and writer Angelique Rosales Salgado addresses the artist’s activation of the archive as a living organism, one that is variably able to conceal and disclose. Riffing on the contradictory reticence of documentation, Rosales Salgado’s text elaborates poetically from the dual definitions of the Spanish word "rayar," which means both "to draw" and "to scratch."

Mónica Mayer, El Tendedero, Los Angeles, 1979. Chromogenic print, 6 13/16 × 10 in. (17.3 × 25.4 cm). © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya

Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

“Escribo como artista, no como crítica.” 1

-Mónica Mayer

A line: una raya. To draw a line or draw the line—to leave a trace. A gesture that has the capacity to bend, excavate, or fold in on itself. Curved or straight, thick or thin, lines lead us to trace the edges of a form, the contours of which define and emphasize a single object or subject. Materially, it could at once be saturated with time while temporally also enduring beyond a fixed beginning and end. In Spanish, the infinitive verb rayar comes from the word raya. Roughly translated, rayar can be defined as “to make lines on a surface”—a boundary, a sketch, a scratch, a path, a horizon, a measure, an edge, a connecting point, an inscription, an emphasis, something that repeats—or even, “to make something yours.” Rayando voy, rayando vengo. Una raya is a distant trace that indicates something that might have been, never was, or has yet to arrive. This accumulation of expressive gestures, at once marking lines of inquiry and scratching away at the autonomy of art, takes shape as a poetic device in Mexican artist Mónica Mayer’s life and practice.

For Mayer, rayar suggests poetic possibility, performative process, and formal technique. Since the early 1970s, Mayer has forged an artistic practice committed to exploring diverse languages of visual and conceptual art through performance, drawing, collage, and printmaking. In tandem with organizing feminist actions and social interventions, she has been an educator, archivist, writer, publisher, translator, curator, critic, and mother. As much an activist as she is a visual artist, her practice is often in friction with traditional conceptions of art(work)—questioning the autonomy of art from social and political life. She has dedicated her life to challenging systems of oppression related to gender and class and critiquing the exclusivity of the art world in Mexico and beyond by creating dialogues that propose better conditions for life. In the context of the quotation that introduces this text—“Escribo como artista, no como crítica” (I write as an artist, not as a critic)—rayar can be thought of as an outcome of the relationship between performance and language that is at the center of Mayer’s practice.

Mayer began her career at a moment in which Mexican artists—primarily in urban areas of Mexico City—promoted a vision of collective practice that came to be known as “los grupos” or the Group Movement. The movement toward grupos developed in response to state violence, suppression, and sociopolitical struggles 2 epitomized by the Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968. 3

During this period, Mayer was at the forefront of art-based feminist activism in Mexico City, investigating connections between visual culture and the social role of women and presenting performance as an emancipatory form of art. Argentine art historian and curator Andrea Giunta charts Mayer’s practice in relation to the particular circumstances of artistic feminism that emerged in Mexico in the late 1970s and early 1980s. She argues that “the Mexican case stands out among the Latin American artistic feminist scenes for its historical formations, its continuity, and the diversity of practices in which its postulates were unfolded.” 4 Emerging from and later leading this radical scene, Mayer prioritizes collaboration as an instrument of aesthetic experimentation capable of counter-hegemonic disruption. Her practice often takes diaristic, participatory form by inviting intimate and diverse responses to femininity without essentializing the relationship between womanhood and the body. At the core of her critical mode of work is the archive, which, she says, with its networks of connection, is “an act of self-defense against invisibility.” 5

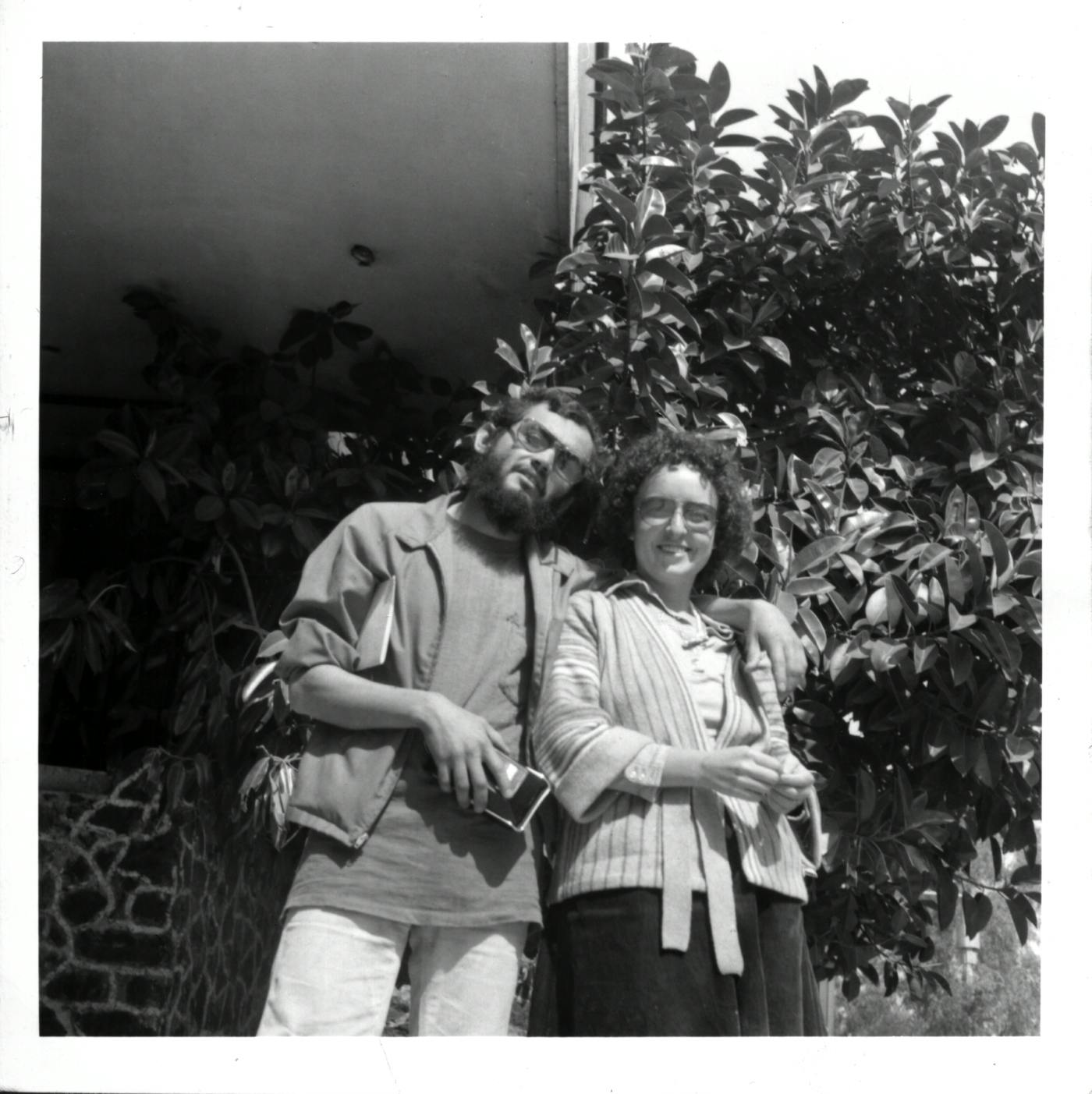

Mónica Mayer and Víctor Lerma, 1978. © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya. Photo: Jorge Arreola Barraza

Mayer's longest collaboration is with artist—and Mayer's life partner—Víctor Lerma, with whom she runs Pinto mi Raya (I Paint My Line), a far-ranging archival project in which pedagogy and performance converge. Together Mayer and Lerma have forged and sustained an independent system of production, documentation, circulation, and activation of art that intervenes in the traditional hierarchy in which institutions have more power than individual artists. In their words, the project is a durational artwork of “applied conceptual art.” 6 Since its inauguration in 1989, Pinto mi Raya has amassed more than forty thousand documents, spanning criticism, blog posts, ephemera, installation images, videos, and sound recordings about contemporary art, some related to their own collaborative and individual performances in public spaces. Their discourse and practice remains immersed in education as a practice itself. Mayer and Lerma continue to congregate artists, form conversation groups, host radio programs, produce independent diffusions of projects, and make digitally accessible countless materials and resources that rewrite (a) contemporary Mexican art history.

Pinto mi Raya began as a gallery started by Mayer and Lerma to support ephemeral, experimental, and ludic exhibitions that were difficult to present in traditional spaces like museums, collections, art fairs, and commercial galleries. Pinto mi Raya joined a coterie of independent artist-run centers that included La Quiñonera, which, founded in 1988, was one of the first experimental art spaces in Mexico; Temístocles 44 (active 1993–95), a collective founded by a group of artists that included Eduardo Abaroa, Abraham Cruz villegas, Franco Aceves Humana, and Sofía Táboas; and La Panadería (active 1994–2002), founded by Miguel Calderón and Yoshua Okón. By the 1990s, Mexico City was animated by a fervent enthusiasm for the exchange of ideas that transcended the confines of existing, restrictive state and institutional structures of the post-1968 regime. Artists across the city turned to DIY formats that could be employed in spaces that belonged to the community. At the time, contemporary art was seen as a marginal practice—pre-internet and pre-globalization—that gave rise to various collective models emerging from a refusal of single authorship and institutionalization. This alternative spirit was underpinned by social engagement, intergenerational dialogue, and reinvention. Above all, there was a curatorial line that was not self-contained but rather existed in a cyclic loop that invited experimental Mexican art to be in dialogue with itself and with an international art scene.

Pinto mi Raya (Mónica Mayer and Víctor Lerma), Nuestras banderas—Our Flags, 2015. © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya. Photo: Yuruen Lerma

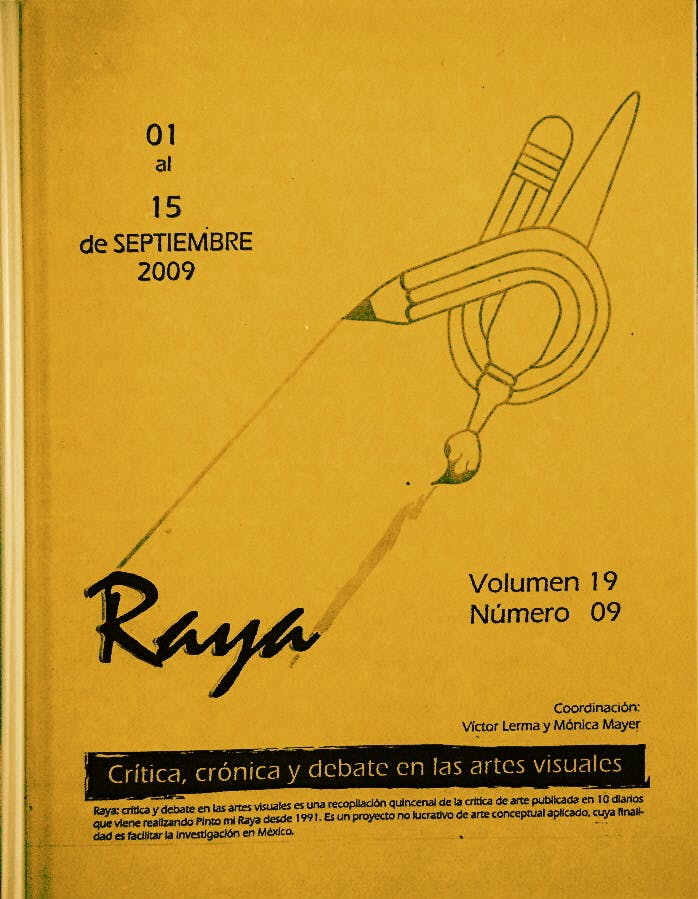

Cover of Raya: Crítica, crónica y debate en las artes visuales 19, no. 9. Eds. Mónica Mayer and Víctor Lerma, 1991–ongoing. © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya

Pinto mi Raya (Mónica Mayer and Víctor Lerma), Archivo Activo: 20 años en el archivo de Pinto Mi Raya, 2011. Box of ten DVDs. © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya

Pinto mi Raya (Mónica Mayer and Víctor Lerma), Archivo Activo: 20 años en el archivo de Pinto Mi Raya, 2011. One of ten DVDs. © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya

Announcement for a panel discussion with Sol Henaro, Pilar García, Víctor Lerma, Mónica Mayer, and Pilar Villela at Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), August 23, 2012. © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya

Propelled by this framework, Pinto mi Raya underlines (in Spanish, subraya, a term used frequently by Mayer and which echoes rayar) 7 the importance of process in their effort to “lubricate” the Mexican art system. 8 Their mission is to converge critique and memory while destabilizing normative institutional dynamics. In brief, Pinto mi Raya intervenes within exclusionary structures in defense of unconventional practices and positions.

This posture frequently takes up an intersectional feminist praxis in the form of participatory performances, like the series Yo no celebro ni conmemoro guerras (I Don’t Celebrate or Commemorate Wars, 2008–ongoing). In this work, Mayer and Lerma engage a radical feminism that questions displays of patriarchal oppression in Mexico within a broader critique of a global cult of war. The project—which centers on the titular statement—has materialized as a performance, through graphics displaying the statement on screen printed flags, caps, stickers, buttons, and t-shirts, and in dialogue with a public that is invited to discuss the implications of the phrase. Here, Mayer and Lerma propose a strategy based on “tagging”—inscribing everyday objects with a mark or symbol made up of words. The work incites a dialogical and reflexive participation with art, bringing into focus the complex tensions between historiography and archival practice, which both interpret past and present yet manifest differently when, in the context of performance, historiography challenges the archive. The printing of this phrase on articles of clothing prompts us to ask how the body is implicated within political conflict, state organized violence, and the validation (or as the title proposes, celebration) of a global military industrial complex.

In projects such as Raya: Crítica, crónica y debate en las artes visuales (Line: Criticism, Chronicles, and Debate in the Visual Arts, 1991–2014), Pinto mi Raya continues to contend with archival work as a practice of continual non(line)ar reflection. The project began as an effort to gather documentation and think pieces on different themes (including criticism, chronicles, reviews, and correspondence) published in various major Mexican newspapers. 9 The title invokes the term rayar in reference to methods of collecting and cataloging. Both are archival strategies and tools of record-keeping that here simultaneously conserve and annotate a memory of contemporary Mexican criticism. Pinto mi Raya’s investment in conversation as critique manifest in archival research emerges as an active line of inquiry imbued with movement and debate: a line that is blurred or smeared. What was once a line transforms into a smudge—a mark that calls attention to itself in question of why it is there.

In commemoration of Pinto mi Raya’s twentieth anniversary, the couple’s project Archivo Activo (Active Archive, 2011) exists as an echo of this material archive. Continually finding new ways to revisit and disseminate the cultural significance of their projects, for Archivo Activo Mayer and Lerma organized a collection of 10,986 texts to piece together an indispensable history of contemporary Mexican art through ten themes: artistic education, public art, performance, architecture, alternative spaces, photography, installation, women artists, criticism of criticism, and digital art. These resources were digitized on ten CDs (each one dedicated to a specific theme), of which twenty sets were donated to public libraries, universities, and art schools in Mexico. Across these and many other projects, Mayer and Lerma’s commitment to access and engagement functions as a unit of measure. A quantifying effort perhaps more concerned with what an archive can do for the present than what it can do for the future. Archivo Activo proposes a broad line of discovery; one energized by aesthetics within the archive that are associative and performative and make visible how artwork can be reascribed meaning via movement, documentation, and redistributed resources.

In the spirit of these historiographic projects, Mayer’s participatory installation El Tendedero (1978) constructed an archive in real time, soliciting responses to a sociological prompt that questioned the public custody of the body. The work was first presented in March 1978 as part of El Salón 77–78: Nuevas Tendencias, a group exhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno (MAM), Mexico City, which took on the theme of the urban environment. The artist created a grid with a clothesline, to which she affixed small pieces of paper printed with the prompt, “As a woman, what I detest most about the city is. . .?” Within the installation, Mayer included responses she had collected from eight hundred women of different ages, professions, ethnicities, and social classes. An overwhelming majority wrote about the threat of violence and sexual harassment throughout Mexico City, particularly on public transportation. Mayer recounts that other women who visited and experienced the work felt inclined to participate, spontaneously taking small pieces of paper and adding their own responses on the back or on any piece of paper that was left. In 1979, Mayer re-created El Tendedero in Los Angeles—where she later lived briefly—as part of the group exhibition Making It Safe.

The 1979 iteration of El Tendedero was installed outdoors in the streets of Los Angeles as part of the multi-day project Making It Safe (1979), organized by Ariadne, a feminist activist group co-founded by performance artists during 1977-82. Their focus concerned social change and violence against women, particularly in the Ocean Park community where the Woman’s Building was located. 10 After learning about a feminist training program in Los Angeles through an interview in the magazine Artes Visuales, Mayer contacted several artists there and traveled to the US to study at the Feminist Studio Workshop. As a reference point, Mayer sought to learn from their methodologies—which revolved around a small group and workshop environment—to bring those organizing tools back to Mexico. While she was attempting to put together the money for her studies, she joined the Movimiento Feminista Mexicano (Mexican Feminist Movement), part of the Coalición de Mujeres Feministas (Coalition of Feminist Women), constituted in 1976, which other groups would soon join. 11 Committed to translation as a connecting act between groups, she eventually developed a cross-border community of friendships and collaborators who shared a political agenda. For Mayer, translation proposes a horizontal dynamic of communication that foregrounds translocal feminisms to consider how histories of colonialism, racial formation, and gender hierarchy affects cultures globally.

Installed in the context of a “street gallery,” El Tendedero in 1979 disrupted the social norms of the gallery and the sidewalk and revealed an interest in new dialogues between artist, object, and viewer. Included in the clothesline installation again were notes with the testimonies of each contributor in response to Mayer’s question, anonymous and hung in no particular order and without analysis. They were presented such that the public could read them and form their own opinions. Still, the specificity of each card was materially emblematic of a representative individual and their experience—written by their own hand. To date, there have been thirty-six tendederos installed at different sites in Mexico and throughout the world, where Mayer has continued to make space for queer and gender-expansive people, including men, to broaden discourse about gendered violence. When I encountered the restaged Tendedero installation in Mayer’s 2016 survey exhibition Si tiene dudas. . . pregunte at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City, I wondered how the experiences of mis abuelitas, mis tías, y sobre todo, mi madre, might be transposed onto this emergent chorus of other women, empowered by an outlet of collective release in the face of the ubiquity of machismo culture. Y mis hermanxs trans, the lineage of queer antepasados past and present that appear within this archive?

Mónica Mayer, Diario de las violencias cotidianas, 1983. Gouache, ink, pastel, and photocopy on paper, 27 1/2 × 35 3/8 in. (70 × 90 cm). © and courtesy Archivo Pinto mi Raya

Mayer's project makes visible the ordinary and exceptional ways in which navigating a city somatically impacts the body. How does safety emerge or recede between architectures, and between people navigating its streets? Where might a proverbial safety be demarcated or foreclosed—for and by whom? Agency in public space is at once embodied, often denied, sometimes reciprocal, always relational—yet asymmetrical, bringing into closer focus our own quotidian negotiation of lines in the relationship to urban space. Artist, writer, and DJ Juliana Huxtable writes,

TRAVEL ACROSS AND, IN AN ACT OF

FREEDOM (NO CARS) AND RITUAL, IN THE

NAME OF PHYSICAL UNBOUNDEDNESS,

EVEN IN SPITE OF POLICING THE SAME…

LINES AND BODIES, CONGENIALITY

IMBUED IN THEIR COLORFUL MOVEMENT

AND ALSO SOMETHING OTHER…

SINISTER, SARDONIC, AND DYSTOPIA. IN

THEIR PREDILECTIONS…

LINE, FIGURES IT GRANTS CERTAIN VITALITIES TO

A REVELATORY POWER

THE NATURE OF THEIR WIDE AND RAPID PROLIFERATION…

SYMBOLS, DEPLETED KINETIC AUDACITY

A SUGGESTION / MARKER

INVITATION TO LINES, BODIES TRANSFORMATIONS

OF EMBOD-IED ENERGIES

IN ON A JOKE / COGNIZANT OF A MISSION

HOMAGE TO THE RECURRENT TENDER AGE 12

While time continues to pass, so too do a city’s shapes, lines, and infrastructures change. Through El Tendedero, Mayer’s investment in archives emerges in her commitment to foreground the ways that the city itself is enmeshed in the lives and histories of people whose presence occupies fluctuating definitions of marginality and visibility. The work considers, perhaps, the ways that different people’s presence in the city is imperiled or empowered by social implications amidst phenomena like economic and housing crises, gentrification, and displacement. While the installation echoes experiences in public space, the clothes(line) as an object itself contests the significance of a domestic space, a place where, in the words of artist June Canedo de Souza, “knowledge about the body, particularly the woman’s body, is imposed.” 13

“OF EMBOD-IED ENERGIES, IN ON A JOKE / COGNIZANT OF A MISSION,” as Huxtable proposes—a liberatory vision and culture-making that multiplies outward with symbolic measure because of its opacity. Worldmaking sometimes emerges on the margins, small pockets of claimed space where folks invent new ways to live and love. In a world where there are no material consequences to gendered violence, Mayer’s Tendederos ask what we might make of collectivity in spite of it, attendant to what José Esteban Muñoz calls “ephemera as evidence.” Ephemera, as Muñoz uses it, is linked to alternate modes of textuality and narrativity like memory and performance. It does not rest on epistemological foundations but is instead interested in following traces, glimmers, residues, and specks of things. 14 This archive, much like the poetic device rayar, is an ephemeral witnessing, a material reality.

...ni somos todas las que están, ni están todas las que somos. . . 15