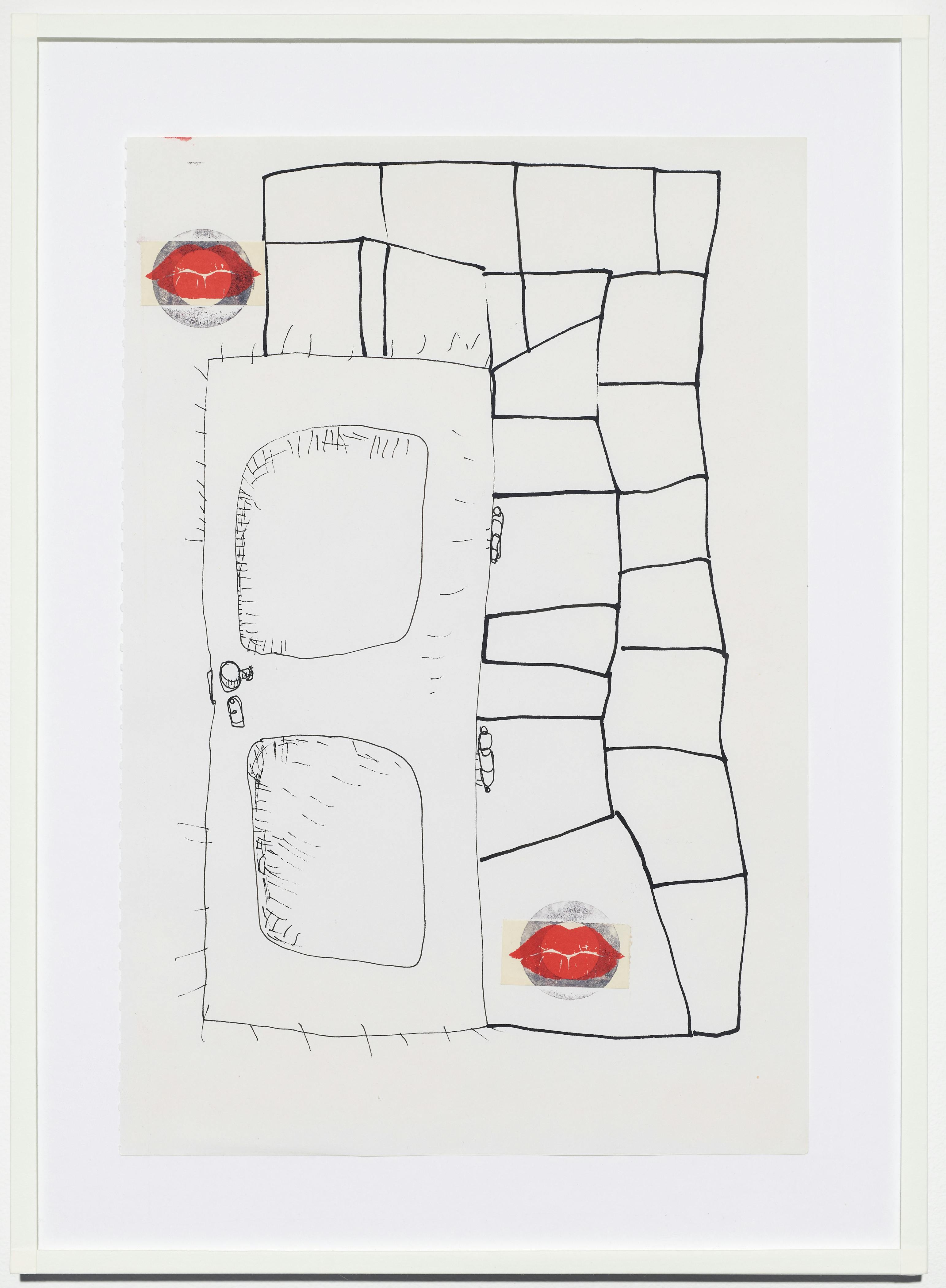

Magali Lara, De lo amoroso, personal, confidencial, etcétera (On the Loving, the Intimate, the Confidential, Et Cetera), 1982. Chinese ink, letter labels, and rubber stamp on paper, 11 3/4 × 7 3/4 in. (29.8 × 19.7 cm). © the artist. Courtesy Oficina Magali Lara. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

Mexican artist Magali Lara has often turned her attention to autobiographical themes, centering her own portrait in early collages and, in later paintings and drawings, seeking out beauty in the everyday. In this text, writer and translator Elisa Wouk Almino reflects upon the intimacy of Lara's practice and suggests ways in which we may interpret the representational immediacy of her works.

Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

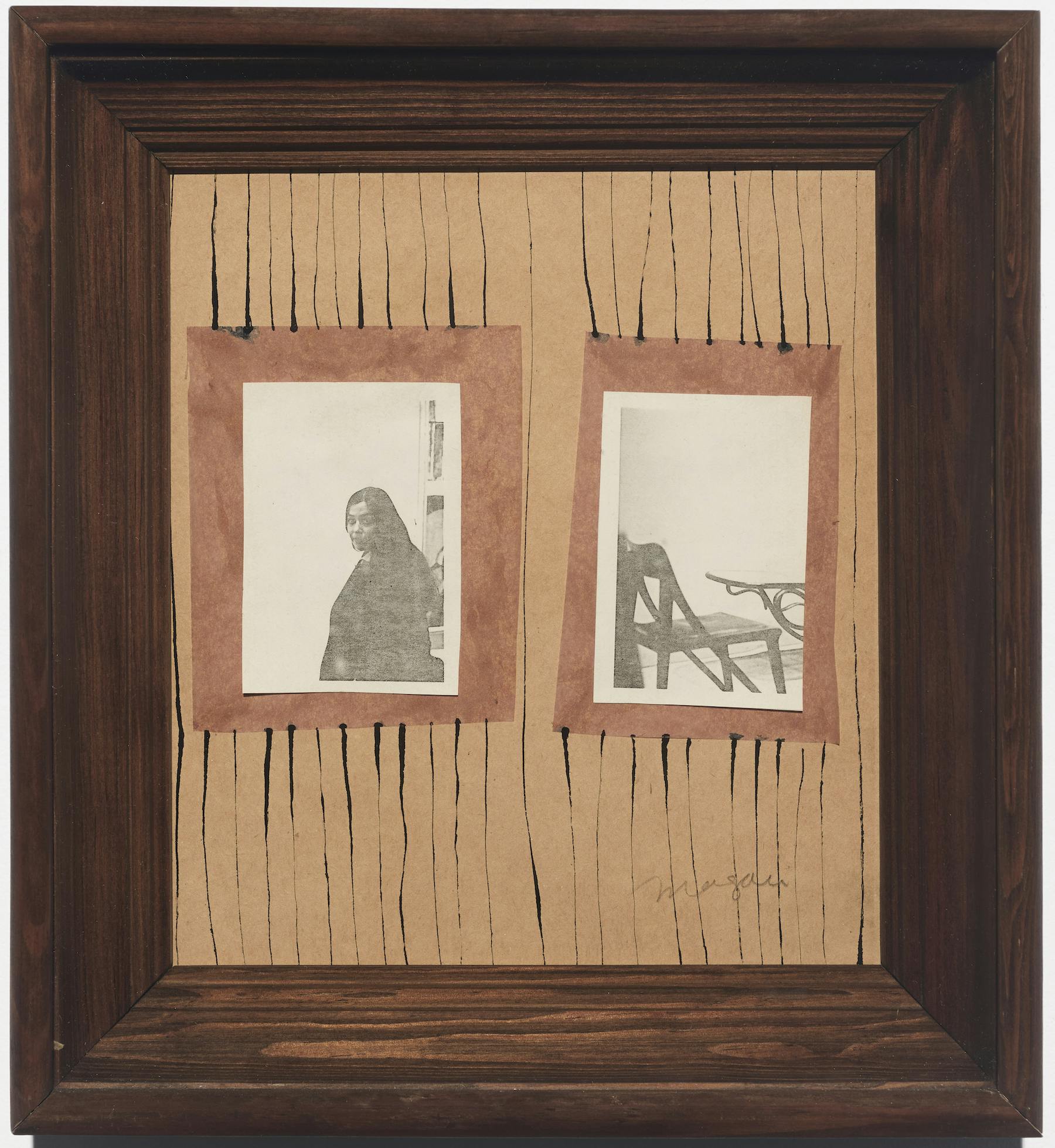

Magali Lara, Untitled, from the series Ventanas (Windows), 1977. Rice paper, photocopy, and Chinese ink on Kraft paper, 12 1/8 × 11 1/8 × 2 in. (30.8 × 28.3 × 5 cm). © the artist. Courtesy Oficina Magali Lara. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

When she was in her early twenties, Magali Lara made a series of collages that she titled Ventanas (Windows, 1977–78): wobbly rectangles that contain elements such as her self-portrait, an X-ray of her body, a photograph of a chair, an opaque wash of gray. These windows didn’t look outward but inward. Eventually, Lara made her way into the space of a house, depicting the bathroom, kitchen, and living room. Sometimes she narrowed in on individual objects: baby bottles, kettles, ironing boards, shower caps, buttons. There is something claustrophobic about Lara’s interiors, as though the light weren’t allowed in. The rooms are yellow, orange, blue, and red, but their tones are muted, thick with paint and layered with the lives and memories that permeate a house over the years.

Lara spent a lot of her childhood indoors. 1 As a child, she began to show interest in the home and its objects, the stories they told her. She started to notice that they “said a lot about people.” 2 She has described the house she grew up in as overcrowded—she had a big family—which meant that “having your own objects... was like having a territory, a geography of your own.” 3

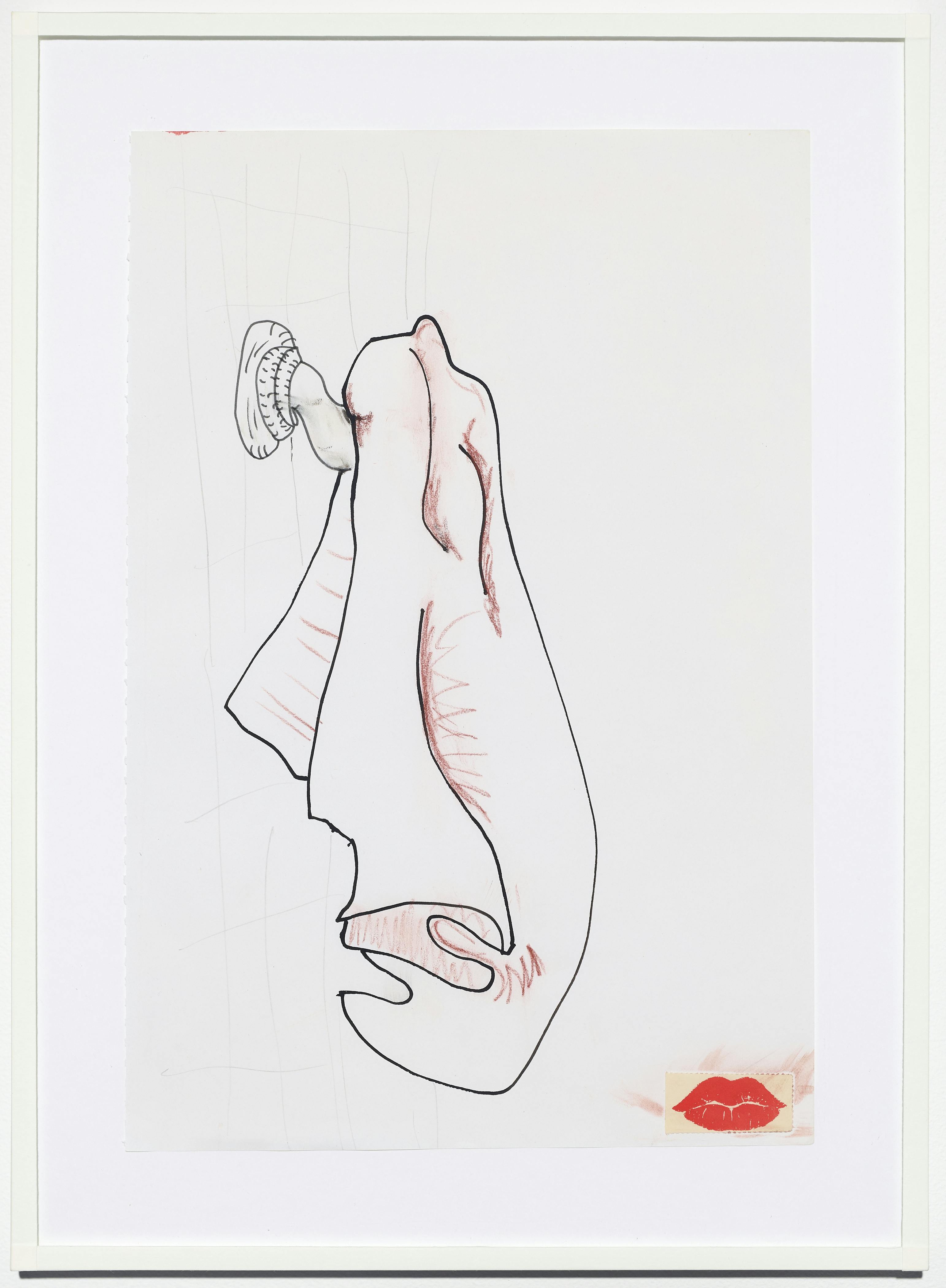

Magali Lara, De lo amoroso, personal, confidencial, etcétera (On the Loving, the Intimate, the Confidential, Et Cetera), 1982. Chinese ink, colored pencil, and letter label on paper, 11 3/4 × 7 3/4 in. (29.8 × 19.7 cm). © the artist. Courtesy Oficina Magali Lara. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

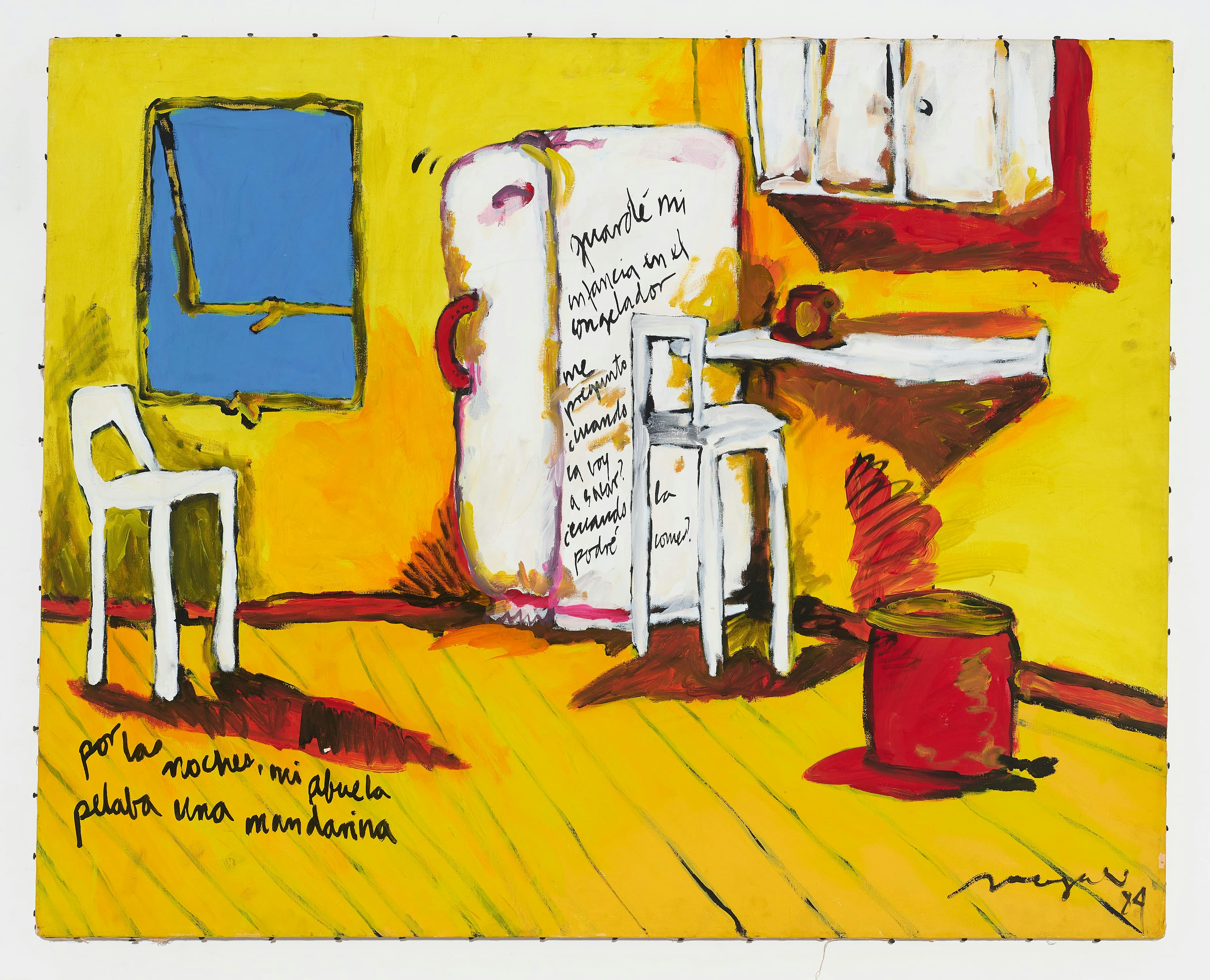

Magali Lara, Guardé mi infancia (I Stored My Childhood), from the series Historias de casa (Stories of Home), 1984. Acrylic paint on canvas, 31 1/2 × 39 3/8 in. (80 × 100 cm). © the artist. Courtesy Oficina Magali Lara. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

Magali Lara, De lo amoroso, personal, confidencial, etcétera (On the Loving, the Intimate, the Confidential, Et Cetera), 1982. Chinese ink, letter labels, and rubber stamp on paper, 11 3/4 × 7 3/4 in. (29.8 × 19.7 cm). © the artist. Courtesy Oficina Magali Lara. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

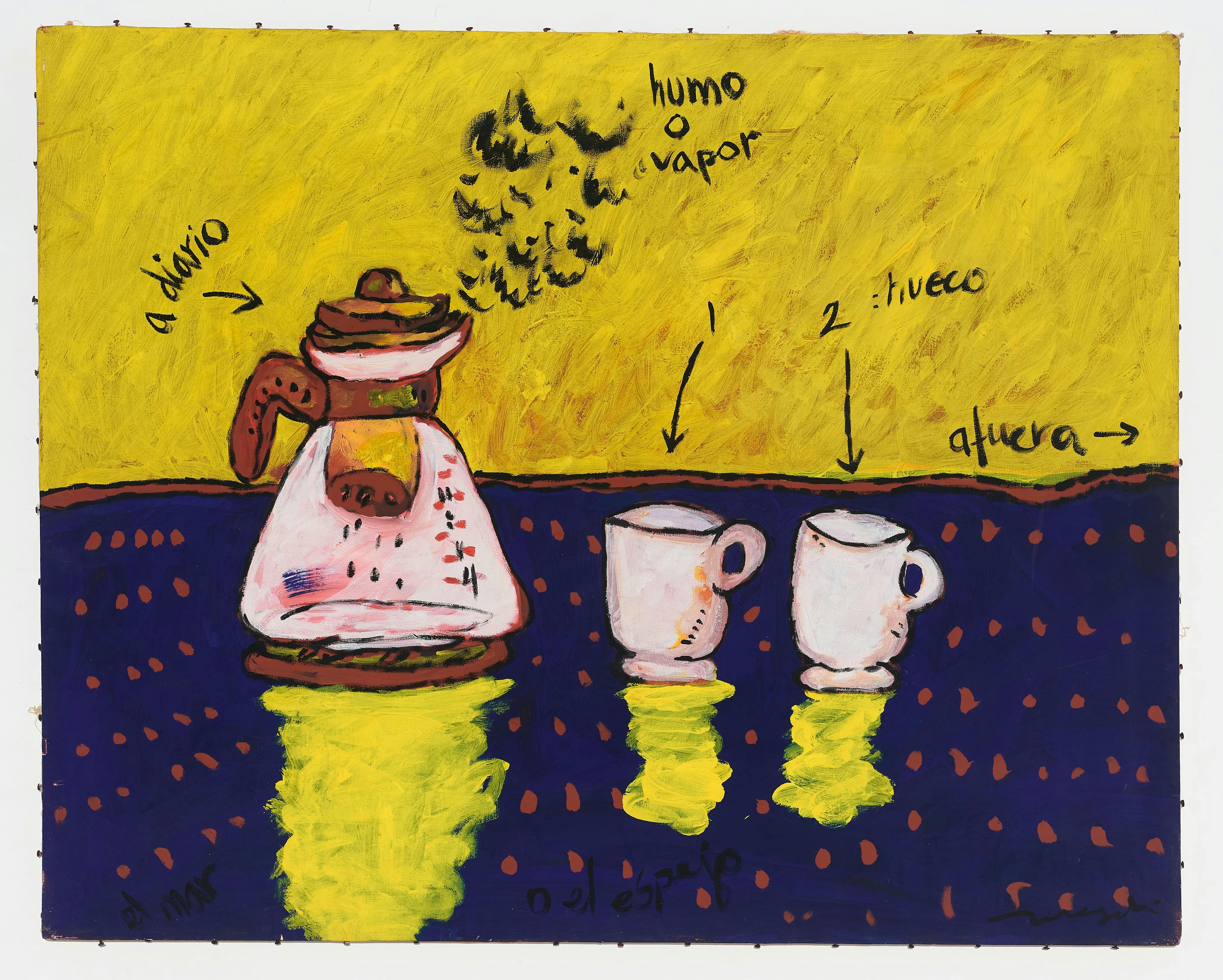

Magali Lara, A diario (Every Day), from the series Historias de casa (Stories of Home), 1984. Acrylic paint on canvas, 31 1/2 × 39 3/8 in. (80 × 100 cm). © the artist. Courtesy Oficina Magali Lara. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

Anyone who has shared a home with another person knows that some corners of a living space end up being relinquished, taken over, designated. We understand that this wall is theirs for decorating. We know that they sit in that chair. A person’s possessions become their stand-ins, making you feel like you’re in their company. In my home there were my mother’s collection of boxes, my sister’s blue desk, my father’s leather slippers.

In paintings and drawings, Lara lays claim to her objects: writing over them or pressing her fingers and lips against the paper. In her 1982 series of collages De lo amoroso, personal, confidencial, etcétera (About Loving, the Intimate, the Confidential, Et Cetera), little red lips wait outside a doorway or lurk beneath a piece of cloth hanging to dry. In a 1984 painting of a yellow kitchen from her series Historias de casa (Stories of Home), Lara scrawls on the side of the fridge: “I stored my childhood in the freezer.” And at the foot of an empty chair: “At night, my grandmother peeled a tangerine.” 4

As a child, my family moved often. Home was not a place, but rather, the things we carried with us. They had, and still have, an aura about them: as though they survived life’s many journeys. Like people, objects age and change. They contain memories we might otherwise carelessly discard or forget. They are sturdy and constant companions.

An object is always about something else, something more: the body that loved that chair, the hand that set that table, the lover who lay in that bed.

In the 1984 painting A diario (Every Day), Lara depicts a coffee kettle and two mugs resting on a table. She literally labels the scene, indicating the “hollow” cups, the “steam” escaping the kettle, and the “daily” activity of drinking coffee. But hidden in the tablecloth are more imaginative observations: she conjures the deep blue fabric as “the ocean,” “or the mirror.” Objects can expand, become other landscapes.

Objects are portals. Since I was a child, I’ve handled my mother’s boxes as though they were holding something precious, as though they were guarding some aspect of her inside them. I’ve returned to our basket of large shells from shores around the world—though most are from Brazil, where my family is from—and picked up the ribbed, colorful forms and held them to my ears to hear the ocean. “I live / in the instant / house / of eternity,” 5 writes the poet Adília Lopes. A home is both about what is immediately there and what is ungraspable, beyond.

This has been the historical allure of still life painting, the genre of art that was popularized in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by the Dutch, and in which perishable foods, glints of light, and blossoming flowers stand for life’s ephemerality—for death and the eternal elsewhere. In more recent years, Lara has also painted flowers, which burst and spread over white backgrounds. She cites Frida Kahlo and María Izquierdo, fellow Mexican painters, as inspirations for her practice, especially their still lifes. Their paintings are more than collections of objects: they are stories about a sense of place, about identity—about what we eat, where we pray, what we collect.

As with Kahlo and Izquierdo, Lara’s artworks about the home are like self-portraits. She started making them in the 1970s, when she was immersed in the feminist movement in Mexico. Lara was a part of a larger group of artists, including Mónica Mayer and Rowena Morales, who were among the first to make explicitly feminist art in Mexico. The home as a metaphor for the woman was a recurring theme; one collaborative installation staged by Lara, Mayer, and Morales was titled Mi casa es mi cuerpo (My House Is My Body, 1983). Depicting her everyday life was a part of Lara’s feminism.

Lara has always made art to understand and express her body. When she was a child, she thought she would become a writer, but when she hit puberty, she became overwhelmed by her physical transformations. Suddenly, “words weren’t enough.” 6 ” She gravitated to images, to how expansive and open-ended they could be—how they “implied everything.” 7 Images seemed to more accurately capture the subjective, imprecise reality of living inside a body.

Still, Lara never left words behind. “To me, drawing and writing are similar—twin sisters,” she has said, acknowledging that “[d]rawings can contain stories the same way sentences can communicate things they leave unsaid.” 8 Her drawings have the energy of speech—sometimes they are expressed with words, but others, with shapes that move and vibrate in space.

“I get to know a room as one gets to know another body, little by little,” Lara has said. 9 The same can be done with her images. The more time spent with them, the more patient you are, the more you can hear them, and the more you comprehend their silences.