Envelope enclosing Sandu Darie’s letter to Nikolai Kasak, 26 December 1959. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

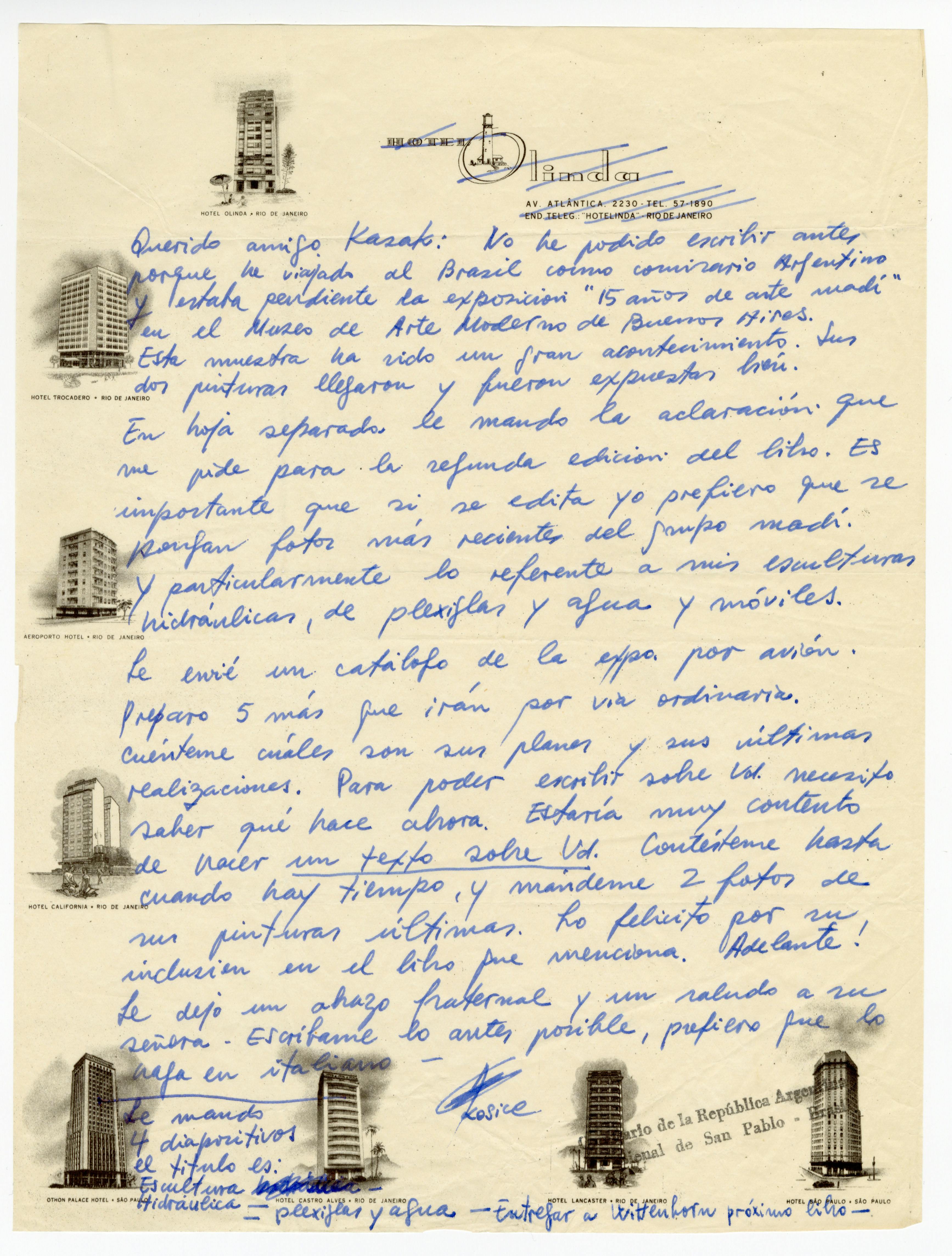

Figure 1: Letter from Gyula Kosice to Nikolai Kasak, 25 January 1950. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

The Writer in Residence series offers scholars the opportunity to conduct research on Latin American art through materials in the ISLAA Library and Archives.

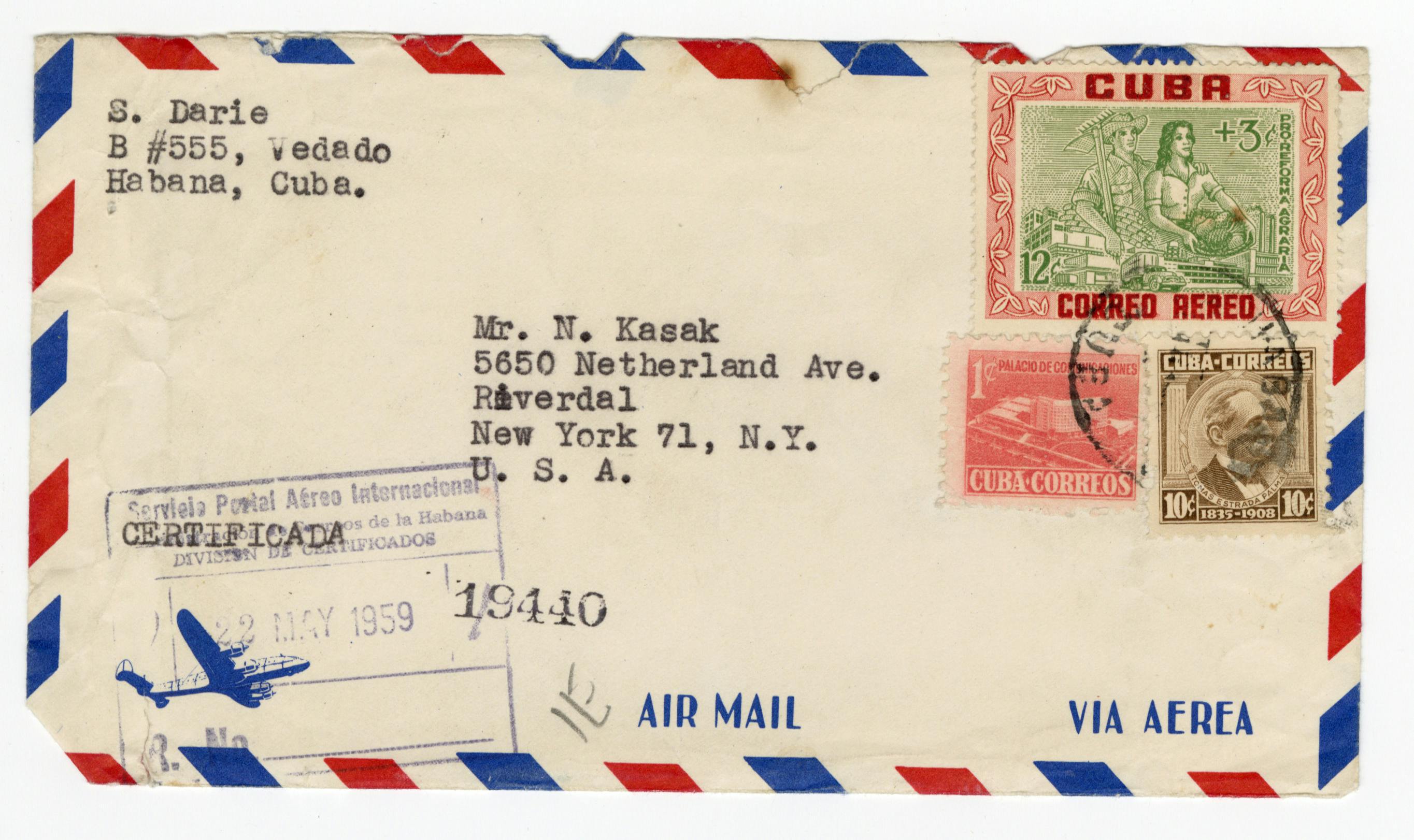

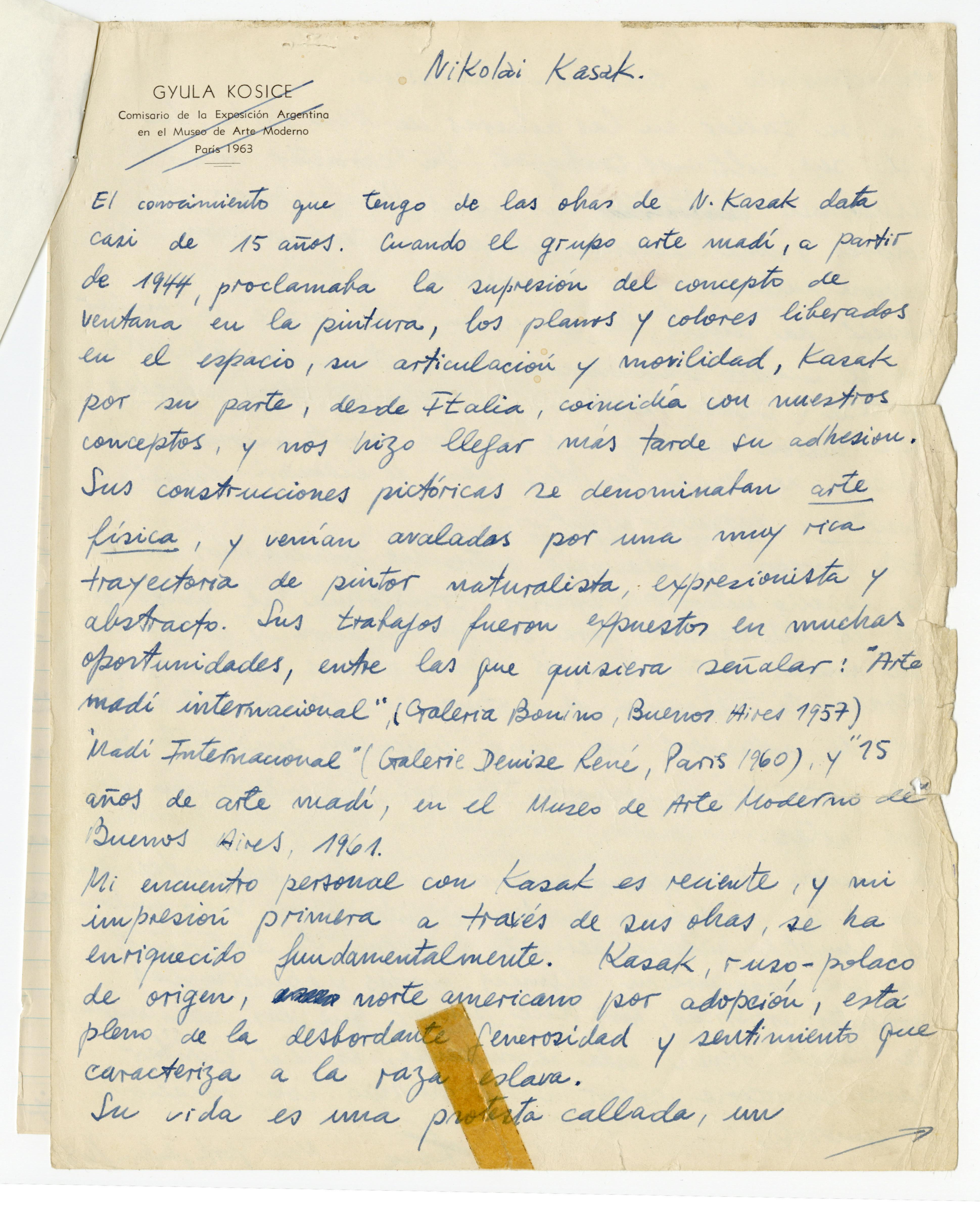

“The thing that filled us most with joy,” wrote the Argentine artist and Madí impresario Gyula Kosice to his Belarusian peer Nikolai Kasak in January 1950, “was that you are situated within the philosophy (realizations) that eulogize our school.” 1 Two versions of this letter reached Kasak in Florence from Buenos Aires, one in Spanish and the other in a tentative English translation (fig. 1). The letter followed Kasak’s initial contact with Madí, an artistic movement founded in 1946 by Argentine and Uruguayan artists that he would soon join as one of their international members for the next decade and beyond. 2 His relationship with Madí, however, always unfolded at a remove, at least in its period of most intense exchange, which spun roughly from 1950 to 1961. This relationship is mapped in the Kasak-Madí archive, lent to the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) by the Estate of Nicolai Kasak. This archive is a testimony to a generative collaboration that brought together artists from different cultural backgrounds and nationalities—not in the flesh but through their works, which appeared side-by-side in exhibitions and publications both in Europe and the Americas. To peer into this archive is to unveil the indirect yet exhilarating circumstances of Kasak’s affiliation with Madí, under which aegis he cultivated and circulated their shared artistic principles. It also exposes Madí’s extensive network of communication, transnational scope, and openness to the notion of simultaneous innovation, confirming the movement’s central role in fostering mid-century abstraction on a global scale. The archive brings to light the challenges and obstacles the Madí artists encountered in the politically polarized climate of the Cold War, as well as the sometimes insurmountable financial and logistical conditions that impeded free artistic exchange. Even more, it reveals the affective dimensions that such mediated exchanges inevitably entailed, tracing the history of long-distance friendships developing alongside professional aspirations, internal disagreements, and the tenets of what Kosice called “our school.”

Figure 2: Nikolai Kasak in his studio in Riverdale, New York, 1950s. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

The Kasak-Madí archive is a testimony to a generative collaboration that brought together artists from different cultural backgrounds and nationalities—not in the flesh but through their works, which appeared side-by-side in exhibitions and publications both in Europe and the Americas.

In his letter, Kosice seized on the facet of Kasak’s work that he thought best captured his affinity with Madí. He saw that, like the artists of Madí and others who had by then joined the antagonistic movement Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención (AACI, which remained strategically unmentioned), Kasak rejected “the mark of remembrance to the internal composition of the painting, leaving aside for always the erroneous conception of ‘window.’” 3 This rejection was a core principle of Madí. In 1944, twenty-year old Kosice had served on the editorial board of the short-lived avant-garde magazine Arturo, in which the Uruguayan artist Rhod Rothfuss had published the foundational article “El marco: Un problema de plástica actual” (The Frame: A Problem in Art Today). 4 Rothfuss argued that the development of a truly abstract visual idiom required a rethinking of the rectangular format traditionally associated with naturalistic painting, one that still carried residues of the comparison that the Italian Renaissance architect and art theorist Leon Battista Alberti drew between a convincing pictorial illusion and a window to a portion of the visible world. 5 Instead, Rothfuss and his fellow Arturo participants embraced nonorthogonal, multipart, and semisculptural supports for their abstract compositions, some of which were reproduced in the magazine. In 1946, after the heterogeneous group that originally gathered around Arturo divided due to ideological differences, Madí was formally founded, with Kosice as its contentious leader. Rothfuss also became a member, and his 1944 article was reclaimed as a Madí manifesto avant-la-lettre. Replacing the windowlike canvas, the irregular frame became a distinctive feature of the movement. 6 Independently from Rothfuss, Kosice, and their associates in Buenos Aires, Kasak too had employed nonorthogonal frames and supports since the mid-1940s, creating paintings that departed from conventional rectangular formats and geometric constructions of painted wood that segmented three-dimensional space. A photograph taken in Kasak’s studio in the early 1950s demonstrates the formal kinship between his works and those that his future peers produced in the Río de la Plata region around the same time (fig. 2). Their artistic credos were also aligned. The first lines of an essay that Kasak wrote on his work around 1945 or 1946 strikingly echo Rothfuss’s argument in Arturo. There, Kasak claimed that the concept of “physical art” that informed his oeuvre was “concerned with liberating the work of art from traditional limitations, e.g., the idea that painting is merely a rectangular, two-dimensional, flat canvas.” 7 Like the artists associated with Madí, Kasak believed that bending and opening the conventional frame underscored the artwork’s connection to the realm of the viewer as a tangible object and, at the same time, rendered this realm inseparable from the formal purity, legibility, and nonreferential character of geometric forms, thereby instilling into everyday reality “a beauty possessing permanent creative force . . . both for the rational and the intuitive mind.” 8 Wedding geometric abstraction with concrete material and physical properties, both the Madí artists and Kasak shaped a utopian practice through which they hoped to synthetize the ideal and the experiential, art and life. This parallel aspiration prompted Kosice to enthusiastically invite Kasak to share more of his work and become a member of Madí: “We invite you, friend Kasak, to send us all possible materials and if you would accept to form part of our group now that your works and those we realize bring us closer, without wishing so,” he proposed in his letter. 9 Calling Kasak a “friend” and marveling at the accidental simultaneity of their respective artistic developments, Kosice concluded his letter with the contention that their incipient dialogue was “the concretion of a style that is evidentially the reflection of our epoch.” 10 This play on the term “concretion” and its consonance with the international phenomenon of Concrete art or concretismo anticipated a decade of intense collaboration through which Kasak and the Madí artists strove to establish themselves in the growing abstractionist scene in Europe and the Americas.

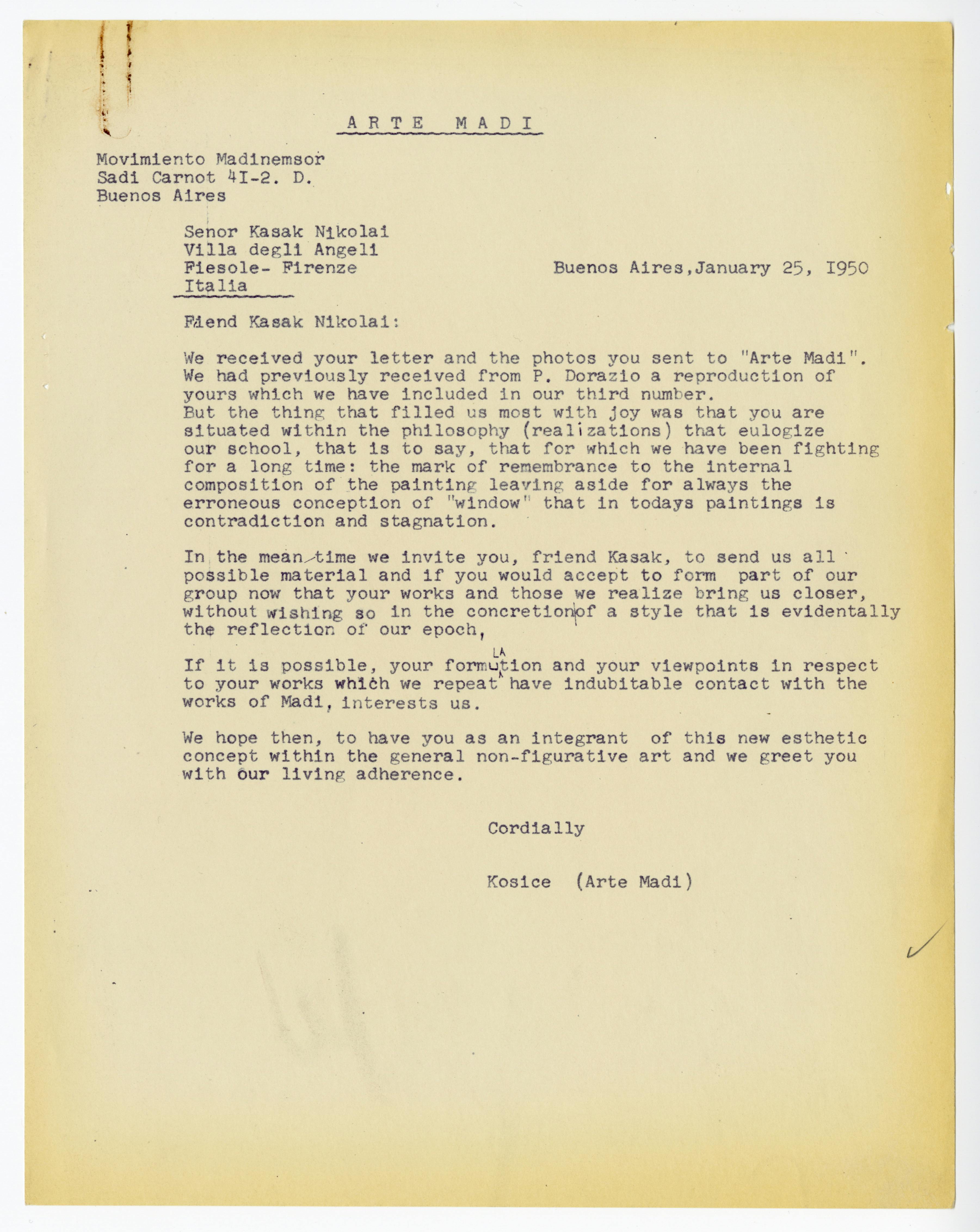

Figure 3: Envelope enclosing Sandu Darie’s letter to Nikolai Kasak, 26 December 1959. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

A photograph taken in Kasak’s studio in the early 1950s demonstrates the formal kinship between his works and those that his future peers produced in the Río de la Plata region around the same time.

Kasak gladly accepted Kosice’s invitation and became an active member of Madí, remaining loyal to the movement after he left Italy for the United States, moving first to Dallas for a brief stint and then settling in New York in 1951. Although Kosice’s correspondence predominates in Kasak’s papers, he was not his sole Madí interlocutor. In September 1954, the Argentine artist Juan Bay sent Kasak a three-page letter in Italian from the town of Castelar, just outside Buenos Aires. He purported to be “here fighting alongside dearest friend Kosice,” whom he defined as a gifted artist as well as an art theorist and organizer “with uncommon abilities.” 11 The self-proclaimed “spiritual leader of the group” and codirector of the magazine Madí, along with Kosice, Bay also underscored his background as one akin to Kasak’s by introducing himself as a former participant in the Italian avant-garde. 12 He also listed the professional connections that he established while residing in the northern region of Lombardy, which ranged from the circles of prewar (and fascist-leaning) movements such as Futurism, Pittura Metafisica, and Novecento Italiano to the abstractionist scene that developed in the mid-1930s around Milan’s Galleria il Milione and the so-called Gruppo Como—all of which would have been familiar to Kasak. Bay also mentioned Fiamma Vigo, one of several powerful art world women mentioned in the Kasak-Madí archive. Vigo, an Argentine-born Florentine art historian and cofounder of the art magazine Numero, was in the process of facilitating a Madí exhibition in Numero’s eponymous gallery in Florence; did Kasak know her, he inquired, and might he be interested in contributing some drawings to the show? 13 Such name-dropping not only allowed Bay to inform Kasak of his stature as an artist, it also fostered a sense of comradery grounded in their common experience as immigrants to Italy. “I returned to the motherland in 1948,” Bay wrote, “but I feel a hundred percent Italian. I love Italy and Italians too much.” 14 The Romanian-born Cuban artist Sandu Darie adopted a similar rhetoric when he first reached out to Kasak in 1959, mailing a cleanly typewritten letter in Spanish from Havana to New York. Rather than emphasizing his and Kasak’s similar backgrounds (they both had Eastern European origins, as did the Slovak-born Kosice), Darie remarked upon their geographic proximity: “You in New York and I here are like neighbors. Perhaps we can even trust to see each other one of these days and talk about our art, our projects, and Madism in general” (fig. 3). 15 Himself an international member of Madí, Darie felt a kinship with Kasak by virtue of their North American milieu, regardless of the growing political tensions between Cuba and the United States in the late 1950s. His optimism about potentially meeting Kasak in person in the near future elided the state of international relations as much as it implied their common distance from Buenos Aires, the point of origin and operational center of Madí.

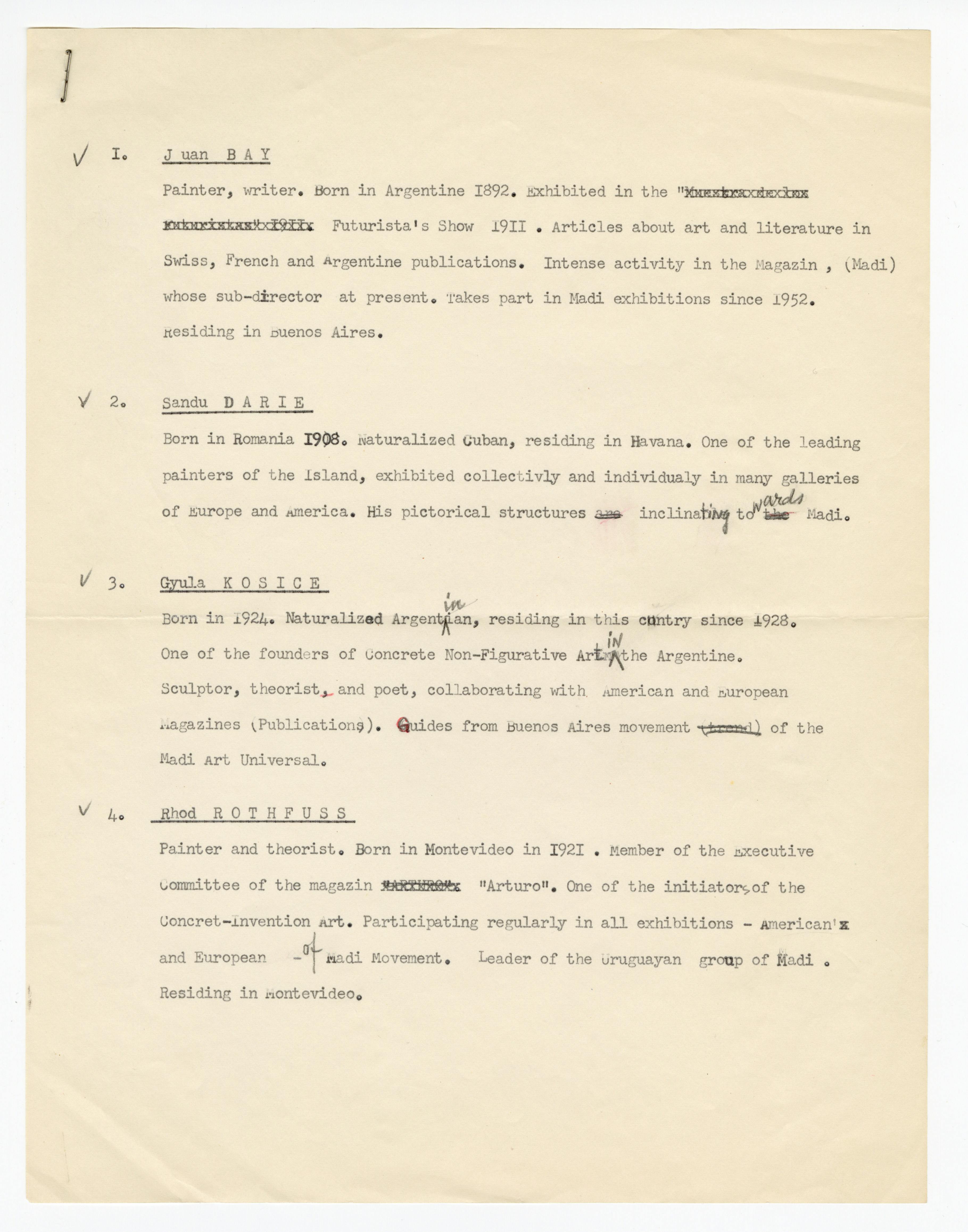

Figure 4: Typewritten biographies of Juan Bay, Sandu Darie, Gyula Kosice, and Rhod Rothfuss, undated. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

Kasak’s strategic position in New York intrigued the Madí artists, who saw in their associate’s new residence an opportunity to circulate their works and ideas in the vibrant artistic hub that the city had become, partly thanks to the influx of European artists, gallerists, and critics fleeing the Second World War. Already in February 1952, still quite green on the New York art scene, Kasak proactively offered to contact the abstract painter Hilla von Rebay, the first director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, about the possibility of organizing a Madí exhibition. 16 She had included some of his works in a group show held at the Guggenheim the previous year, and he believed that she might be interested in the experiments of his Río de la Plata peers, though he suggested that a letter from Kosice on official Madí letterhead might help make their case. 17 Unfortunately for them, von Rebay resigned from her role just the following month due to health reasons and tensions with the museum’s board of trustees. 18 Although she remained involved with the museum in her quality of director emeritus, whatever sympathy she might have had for Madí never led to an exhibition. 19 Undeterred, a few years later Kosice shipped a few of his, Bay’s, Rothfuss’s, and the Italian-born Argentine artist and Madí member Salvador Presta’s works to Kasak, along with some typewritten biographies, in case the latter managed to organize a group show after all (fig. 4). 20 He asked Kosice to set aside one of his articulated sculptures as a gift for the Guggenheim to be personally delivered to James Johnson Sweeney, von Rebay’s successor to the museum’s directorship. 21 As no works by Kosice are currently in the Guggenheim’s collection, this brazen maneuver was likely aborted. Kasak also volunteered to contact the art dealer Rose Fried, whose New York gallery represented artists working in nonobjective visual idioms from multiple regions, including the Southern Cone. Pioneers of abstract art such as Vassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian were part of Fried’s roster. The Uruguayan Joaquín Torres-García, whose work and theories constituted an important model for Madí, was one of her main protégés. 22 Kasak’s friend and Kosice’s acquaintance, the Italian painter Piero Dorazio, also collaborated with her. 23 This project did not come to fruition, despite Kosice’s and Bay’s wildest ambitions; in the same 1954 letter in which he first contacted Kasak, Bay confidently wrote:

"We think to make a trip to the United States, with the precise intention to divulge our ideas, alongside you, by means of exhibitions, classes, and conferences. In cultural establishments and universities. But first of all, we would like to organize in New York a show of Madí temperas. A show that you could organize, with other cities as destinations." 24

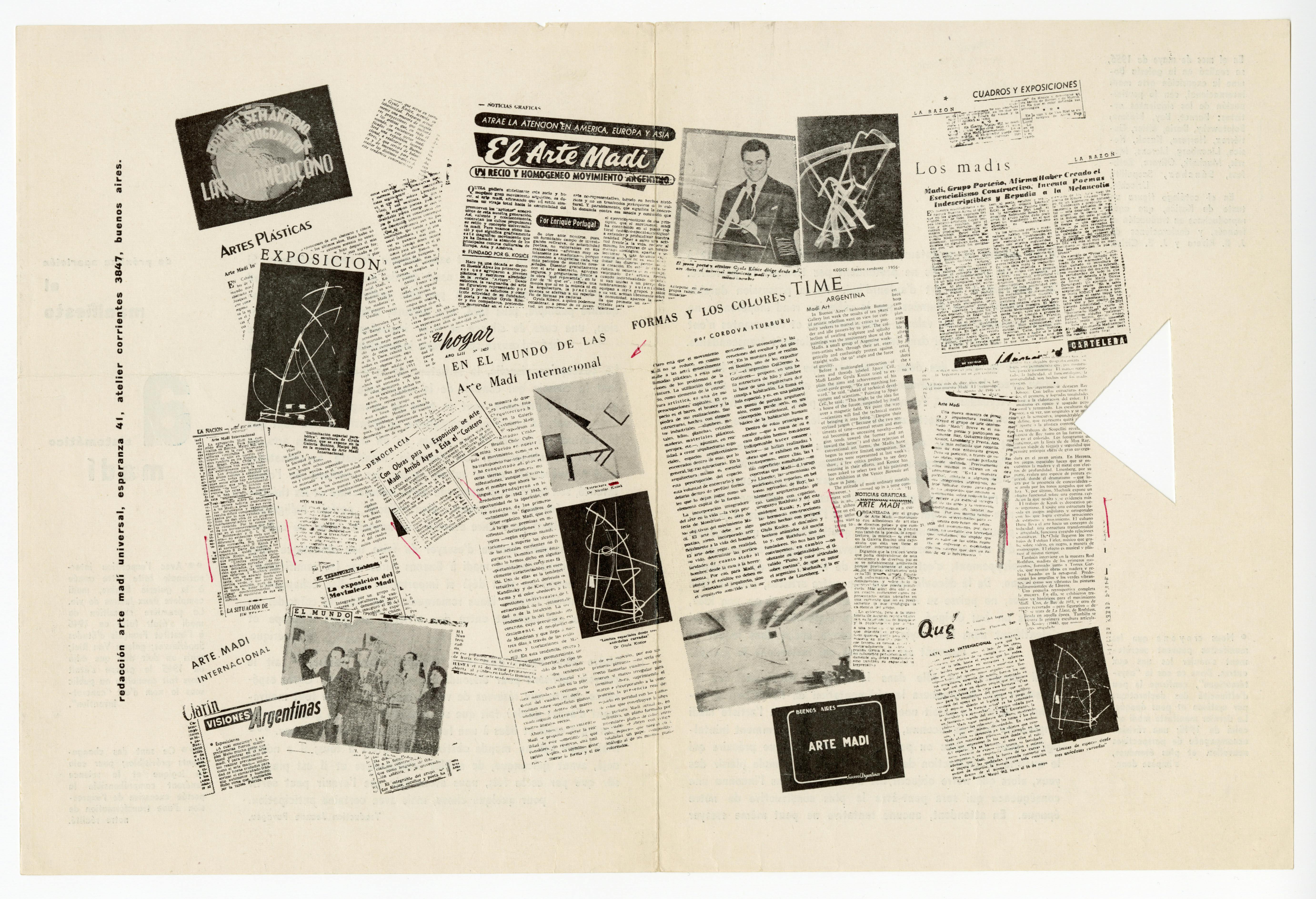

Figure 5: Montage of news articles dedicated to Madí, with a reproduction of a work by Nikolai Kasak at center-left, marked in red ink. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

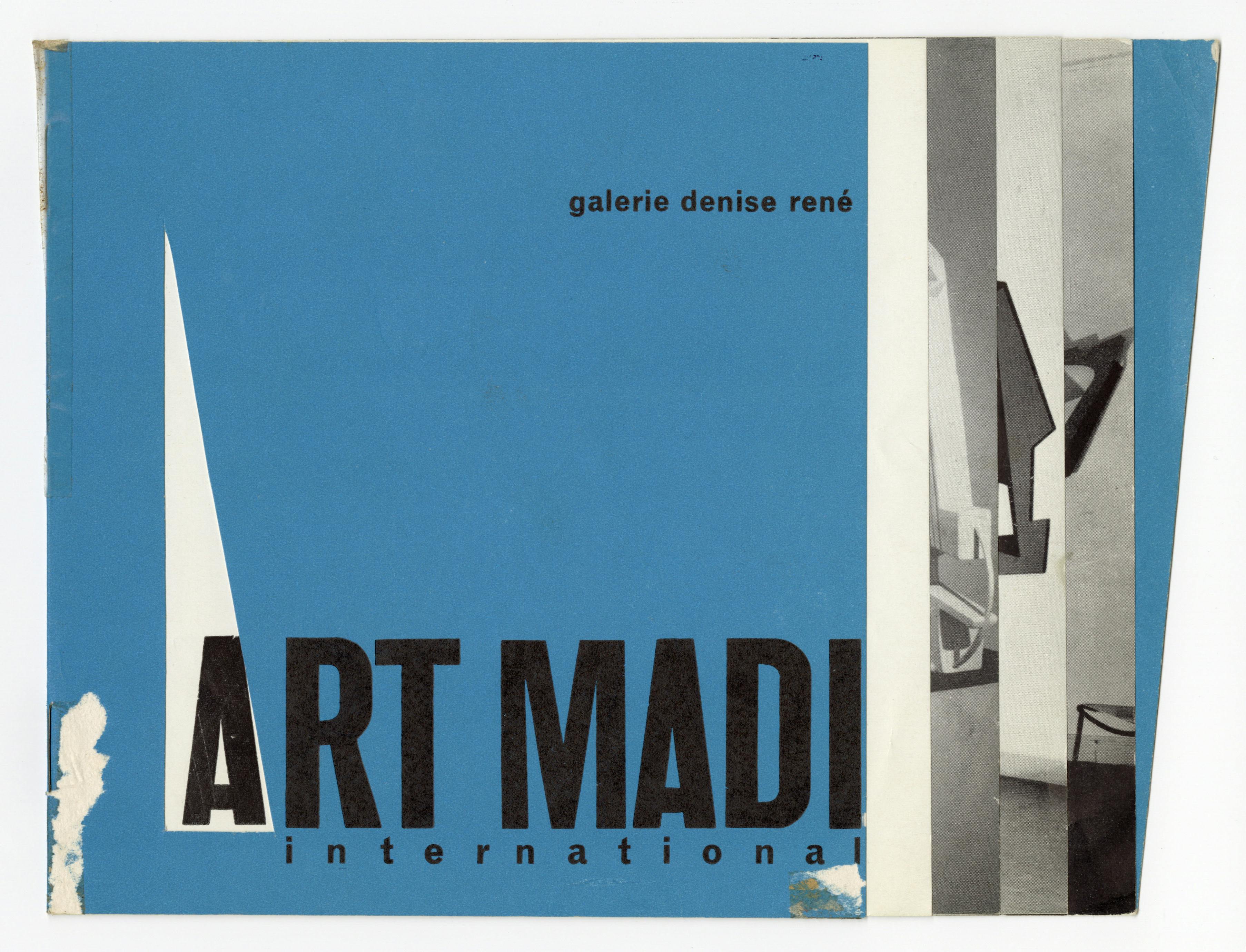

Figure 6: Cover of Art Madí International, catalogue of the exhibition held at the Galerie Denise René in Paris, 1958. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

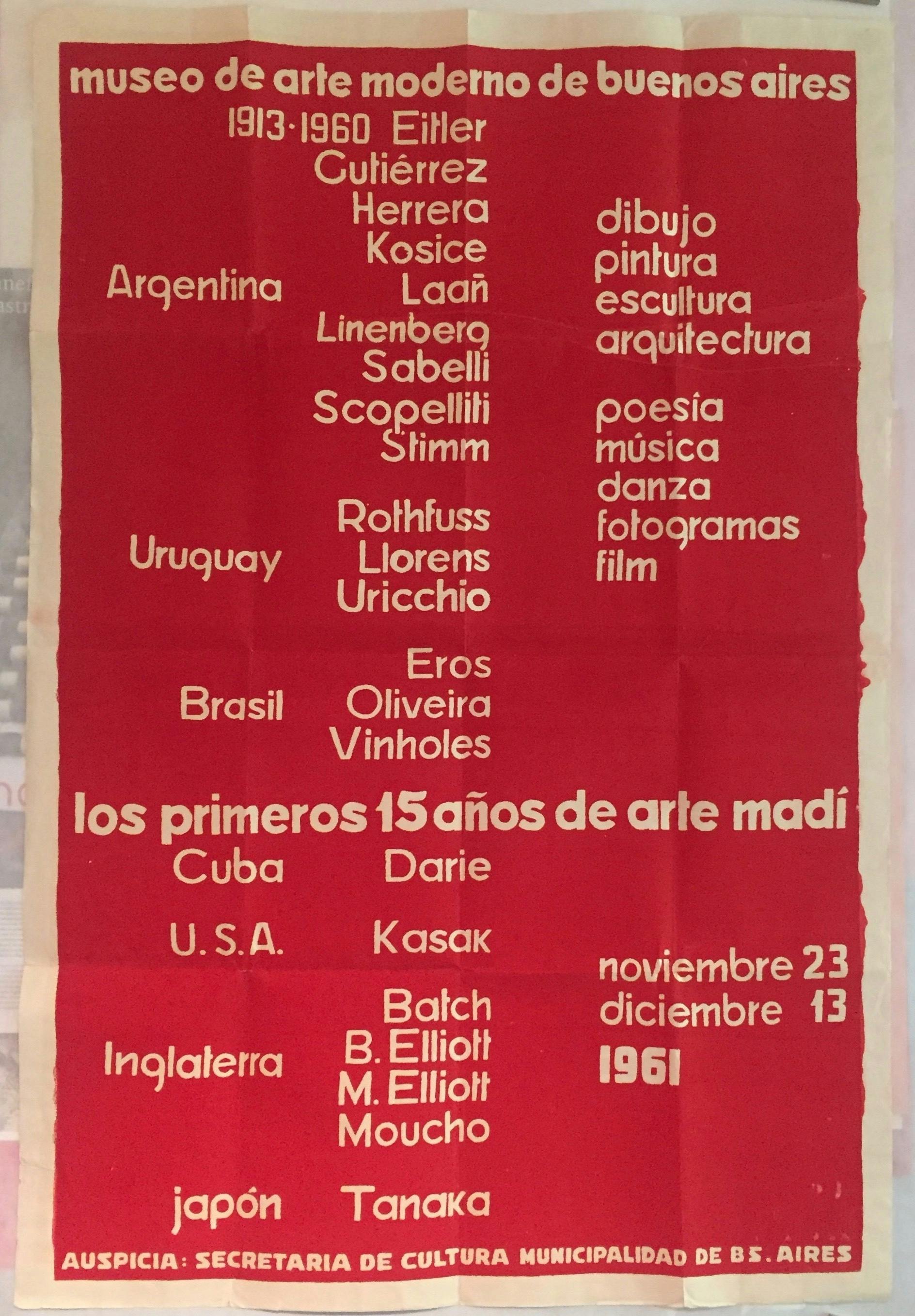

Figure 7: Poster for the exhibition 15 años de Arte Madí at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 1961. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

Kasak managed to advertise Madí and its practitioners in the United States by including them activities with the American Abstract Artists, a New York–based group he joined in 1955.

Bay hoped to physically travel with Kosice to New York and even dreamt of a platform through which to circulate the principles of Madí and showcase the group’s works—not just in the metropolis but in different cities as well. After Kasak responded hesitantly, Bay did not take long to reframe his expectations, admitting that the plan, at least for the moment, was unrealistic. 25 Yet, Kasak successfully managed to advertise Madí and its practitioners in the United States by including them in some of his activities with the American Abstract Artists (AAA), a New York–based group he joined in 1955. For example, he facilitated the publication and translation of Kosice’s essay “Non-Figurative Art Trends in Latin America” in the AAA edited volume The World of Abstract Art, which appeared alongside texts authored by several protagonists in the development of abstraction in the twentieth century in Eastern and Western Europe, the Americas, and Japan, as well as interviews with the Alsatian artist Hans/Jean Arp and the Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo. 26 Later, Kosice sent Kasak a manuscript he wrote in English, “Essence and Appearance of Madí,” to be featured in another United States publication, hoping that his friend could use “all your influence so that we are well represented.” 27 To all effects, Kasak was Madí’s agent in New York, often relaying messages and distributing materials from Kosice to AAA peers such as Will Barnet, Ilya Bolotowsky, and George L. K. Morris. 28

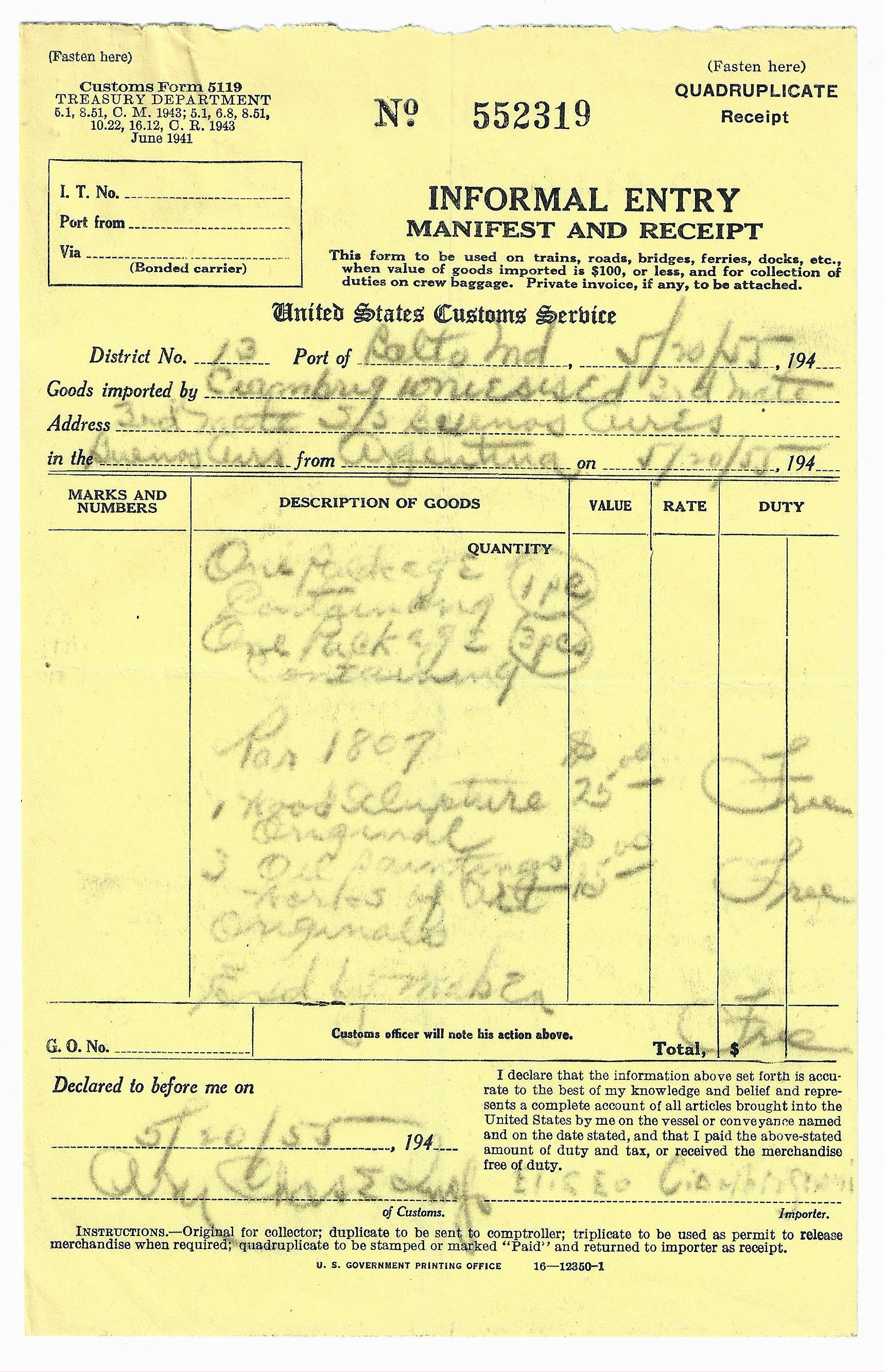

In return, Kosice and Bay prominently featured Kasak in Madí exhibitions and publications, both in Argentina and abroad. As the art historian María Cristina Rossi has demonstrated, throughout the 1950s and early 1960s the artists involved Kasak in initiatives that helped Madí coalesce into a distinctive brand—that of a relentless avant-garde force transcending geopolitical boundaries. 29 They began by featuring Kasak’s works in the second issue of Arte Madí Universal even before they initiated contact, later dedicating a profile to him in the fourth number of the magazine and a whole spread in the fifth, as well as reproducing his works in various Madí manifestos (fig. 5). 30 They also included two of his works on paper in the Madí exhibition that Vigo organized at Numero in 1955, and tried to enlist him for an unrealized section of the twenty-eighth Venice Biennale. 31 They showcased his work in the 1956 exhibition Arte Madí Internacional (International Madí Art) at Galería Bonino in Buenos Aires and, two years later, in the groundbreaking show that Kosice organized at the Parisian gallery of the dealer Denise René (fig. 6). As Kasak’s active dialogue with Madí began to die down in the early 1960s, the artist and writer Diyi Laañ picked up her husband Kosice’s correspondence and invited him to represent the United States in the 1961 retrospective 15 Años de Arte Madí (15 Years of Madí Art) held at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires (MAMBA), an event that sealed the movement’s reputation as an international phenomenon (fig. 7). 32 These initiatives were all coordinated in epistolary form, usually on Madí letterhead and rife with slogans such as “¡Adelante con Madí!” (Onward with Madí!). 33 They allowed Kasak to display his work in metropolitan centers far from where he lived, planting him on the map of midcentury abstract art. These endeavors also permitted him to maintain contact with former associates in Italy and to generate new relationships with colleagues in Paris and the Southern Cone, imbricating him with a professional network whose global span mirrored the utopian idea that abstract visual idioms could bridge nations despite political and linguistic barriers (fig. 8). Yet, such projects were far from simple to realize and required considerable organizational and financial efforts. The Kasak-Madí archive brims with strategic plans for arranging the transportation of artworks, avoiding custom taxes, and covering publication costs. Luckily, the booming tourism industry provided artists with a convenient shortcut for exchanging artworks across various continents. When Kosice sent a selection of Madí works to Kasak in 1955, in order to circumnavigate import fees he entrusted them to an inexperienced young man, one Eliseo Ciambrignoni Pilotín, who travelled on a cargo ship from Buenos Aires to Baltimore (fig. 9). 34 He adopted this strategy again in 1957, arranging for Fanny Balán, an Argentine friend of his, to pick up from Kasak’s studio some of the works he hoped to bring to Paris for inclusion in the exhibition at Galerie Denise René. 35 Kasak accompanied this precious luggage with ten packets of Perspex powder (a plastic derivate of Plexiglas hard to find in Argentina), which Kosice had requested for his kinetic hydraulic sculptures, along with two copies of The World of Abstract Art that were probably destined to Bay and Rothfuss. 36 In order to pay each other back and to share revenues from any works they managed to sell, the artists submitted wire transfers using previously agreed-upon pseudonyms (including Kosice’s birth name Ferdinand Fallik) or sent international money orders that sometimes got lost in the mail. 37 On at least one occasion, Kasak served as an intermediary for a payment on behalf of Darie, who was not allowed to transfer US dollars from Cuba because of the United States’ embargo on the island. 38 Overall, practical considerations almost outweighed aesthetic and ideological exchanges in their correspondence.

Figure 10: Letter from Juan Bay to Nikolai Kasak, 11 December 1955. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

Figure 11: First page of Gyula Kosice’s manuscript titled “Nikolai Kasak,” 1965. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

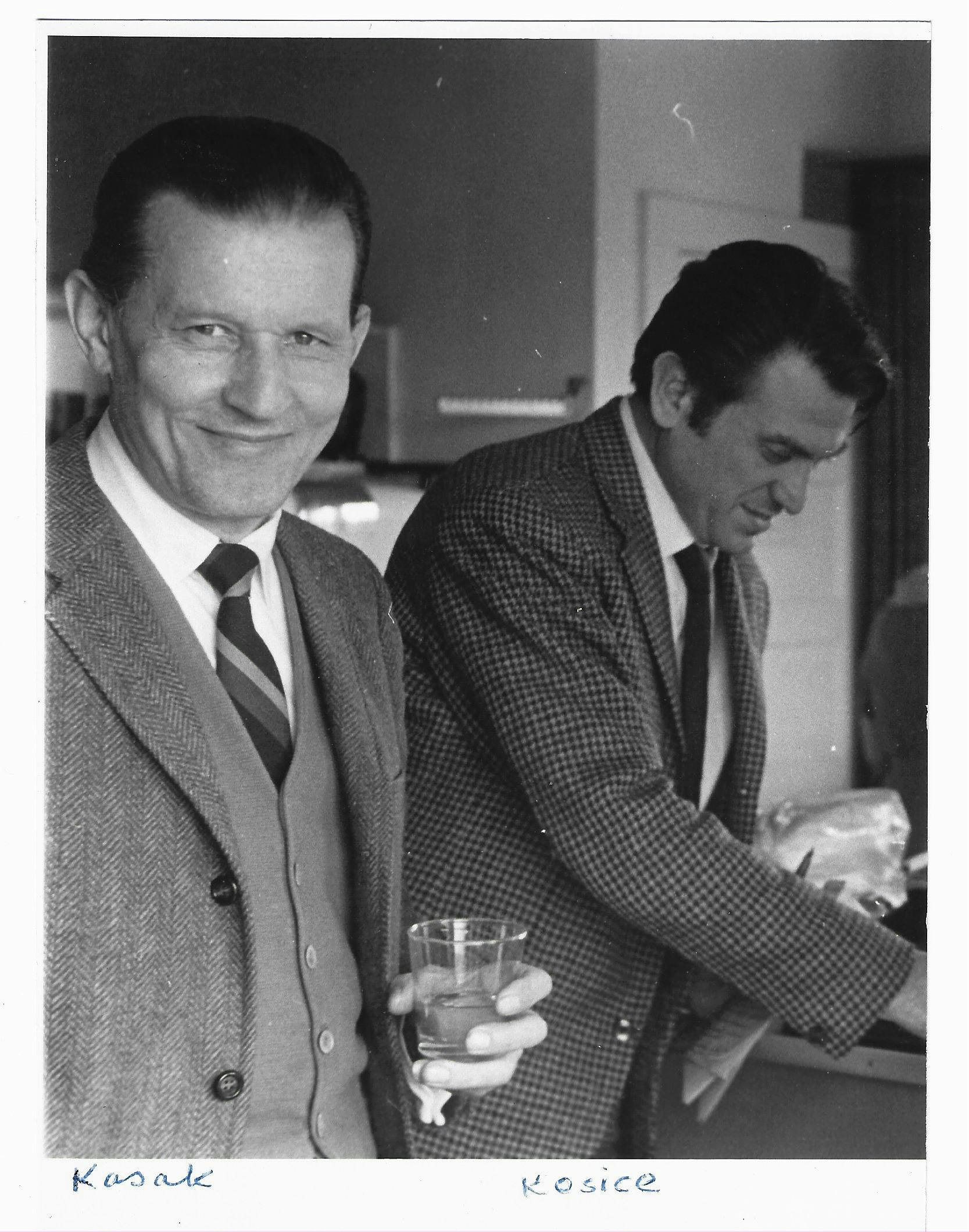

Figure 12: Nikolai Kasak and Gyula Kosice in New York, ca. 1968. Estate of Nikolai Kasak

Kosice and Bay prominently featured Kasak in Madí exhibitions and publications, both in Argentina and abroad.

From the start, messages of a personal nature also abounded, showing that at the same time as they established professional relationships, Kasak and Kosice, Bay, and Darie gradually built friendships that were inseparable from their artistic dialogue. Kasak was quite proactive in this sense. Early on, he asked for photographs of Kosice and Rothfuss, so that he could better picture his interlocutors. 39 In 1955, he wrote with urgency to Bay to inquire about his family’s and Kosice’s safety following the coup that deposed the Argentine president Juan Perón. Bay, on his part, reassured him that both he and Kosice were safe, being “apolitical and, on top of that, prudent citizens.” 40 Unlike their AACI colleagues, whose leftist principles were intertwined with their avant-garde practice, the Madí artists shied away from clear-cut political affiliations. Bay also took the opportunity to proudly describe his two daughters Anna Maria and Mirella Bay, respectively, a poet featured in the 1955 Antología de la poesía madí (Anthology of Madí Poetry) and a painter and ceramicist. He shared that Mirella had recently undergone a complicated surgery to remove some kidney stones, recounting in detail her ailments and his fatherly preoccupations. 41 When she began to suffer life-threatening complications shortly thereafter, he did not hesitate to implore Kasak to send to Buenos Aires two bottles of Silvol, a medicine available in the United States but hardly accessible in Argentina (fig. 10). 42 As soon as he was able to, Kasak mailed Bay the drug, securing his eternal gratitude and prompting Kosice to write: “Much obliged for your trouble over the remedy for Mr. Bay.” 43 Good wishes for holidays and festive occurrences were also part of their exchanges. In a December 1959 letter, Darie thanked Kasak for sending him an Easter card and in turn congratulated him on the recent birth of one of his children; his son Alexander Nikolai was born in December 1955, and his daughter Christina in November 1959. 44 Friendly messages coexisted with veiled accusations that betrayed Madí's internal tensions, often fueled by Kosice’s effervescent personality and domineering leadership. Bay, for instance, could not help revealing to Kasak that he had to take a stance against Kosice at a committee meeting deciding which artists to feature in the upcoming issue of the Madí bulletin they edited together. According to Bay, he had to fight Kosice to ensure that the publication exclusively focused on members of the group, “so that all of them could be known across the eight corners of the compass rose.” 45 Not without some pride, he alleged that Kosice complied “unconditionally” after he threatened to leave the group if his plea went unheard—a capitulation about which he begged Kasak to “maintain all secrecy.” 46 Kasak rarely expressed acrimony towards Kosice, though his frustration is palpable in a few passages where he repeatedly begs his Argentine peer not to modify the titles of his works in Madí publications. To be sure, the relationship between the two cooled in the early 1960s; when Kosice invited Kasak to participate in the 1961 retrospective at MAMBA, he lamented not having heard from his colleague in a long time, and he and Diyi Laañ had to follow up with Kasak multiple times to secure his commitment to the exhibition. Explicit tensions arose years later, when Kosice seemingly ignored Kasak’s request to return some of the works he had sent to be featured in exhibitions that had remained in the Madí leader’s possession, and to donate a selected few to MAMBA in his wife Janina Kasak’s name. 47 When Kasak read Kosice’s 1967 autobiography, he remained bitterly disappointed not to have found a single mention of his name, and was sure to let his former associate know. Yet, the two artists maintained sporadic contact until at least the early 1980s, as the pamphlets advertising various exhibitions of Kosice’s works in the Kasak-Madí archive attest. 48 Their mutual respect and admiration as artists remained intact long after they managed to meet in person on occasion of Kosice’s first trip to New York in July 1965, when he traveled from Paris to attend his solo exhibition organized by the art dealer Terry Dintenfass. 49 While still in New York, Kosice mailed Kasak a manuscript that he wrote in Spanish shortly after their reunion (fig. 11). 50 This text, along with an attached English translation drafted in pencil and autographed by its author, provides a detailed account of Kasak’s productive involvement with Madí over the course of “almost fifteen years,” ever since the Belarusian artist, “from Italy, coincided with our concepts.” 51 Fresh from Kasak’s New York studio over a decade since their first contact, Kosice still seemed delighted at Madí’s and Kasak’s simultaneous yet independent discoveries. “My personal encounter with Kasak is recent,” he admitted, “and the initial impression I derived from his works has been fundamentally enriched,” clarifying that “Kasak, Russian Polish by birth, North American by adoption, is full of the overflowing generosity and feeling that characterizes the Slavic race.” 52 In a particular passage worth quoting at length, Kosice expressed in no uncertain terms his admiration for Kasak’s practice and its affinity with Madí:

"Kasak had the conviction and the courage to break with the traditional picture, the easel painting, the canvas. This rupture liberated other energies that were channeled in the constructions that Kasak had the happy idea to call “positive-space” and “negative-space.” This process of relations between forms, colors, interior and exterior space transforms the wall that is the intermediary for their presentation and introduces new architectonic constructions. It certainly exceeds the definition of painting and sculpture. The created object thus acquires an unforeseen dimension that characterizes our time: the integration of the arts." 53

Like the Madí artists, Kosice suggested, Kasak rejected the rectangular, windowlike frame to create objects that transcend medium-specific categories, activate the lived-in space of the viewer, and give concrete form to an idealistic dimension in which art and life blend. Along with a photograph likely taken two years later that depicts Kasak and Kosice smiling complicitly in an interior space, this text is one among scarce pieces of evidence of the two artists’ direct encounters (fig. 12). As the Kasak-Madí archive documents, their relationship—as well as that between Kasak and Bay and Darie—mainly evolved at a distance, across geographic and linguistic barriers. Their epistolary dialogue nonetheless afforded them to weave together aesthetic, organizational, and biographical concerns and to cultivate the utopias central to their shared artistic credo—“our school,” in the words of Kosice’s initial 1950 letter—through both their artworks and international comradeship.