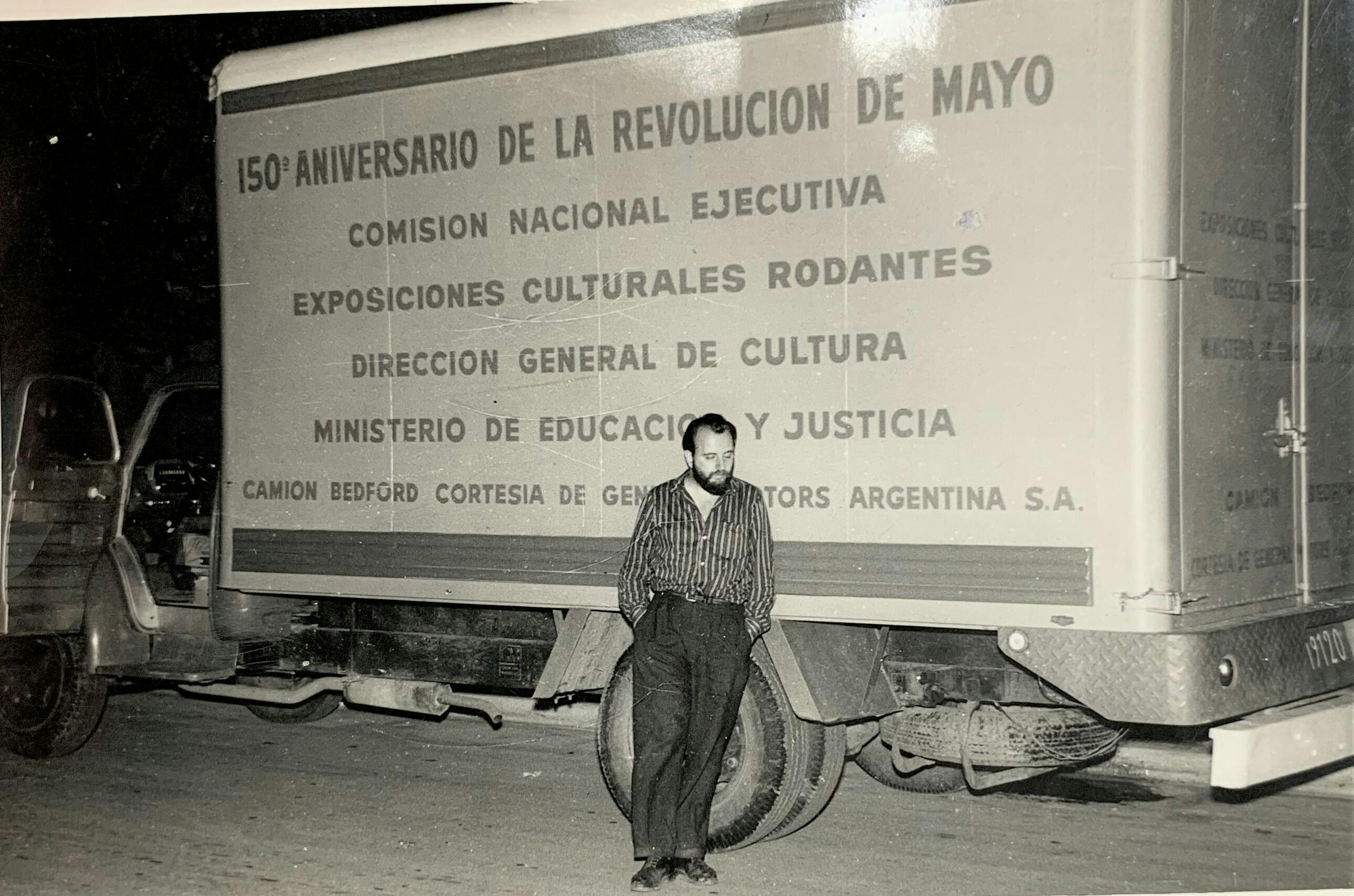

Fig. 16. Alberto Greco standing next to a Bedford truck. Lila Mora y Araujo Archive. Centro de Estudios Espigas–Fundación Espigas Collection

From the Desk of. . . invites scholars to fill gaps in English-language reference materials on Latin American art by developing research on movements, geographies, and methodologies.

This essay aims to illustrate the experiences that shaped Greco's movement toward Arte Vivo.

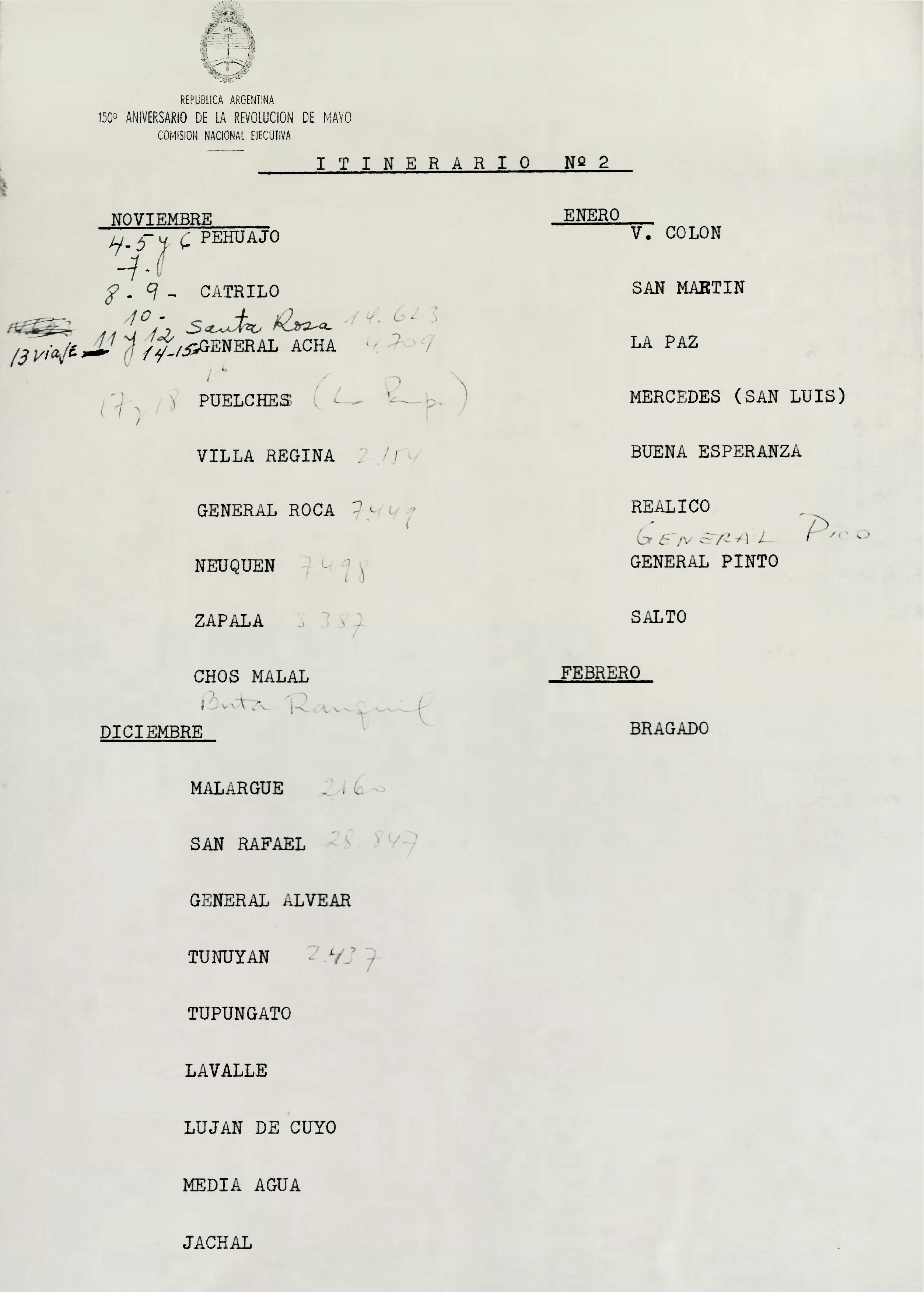

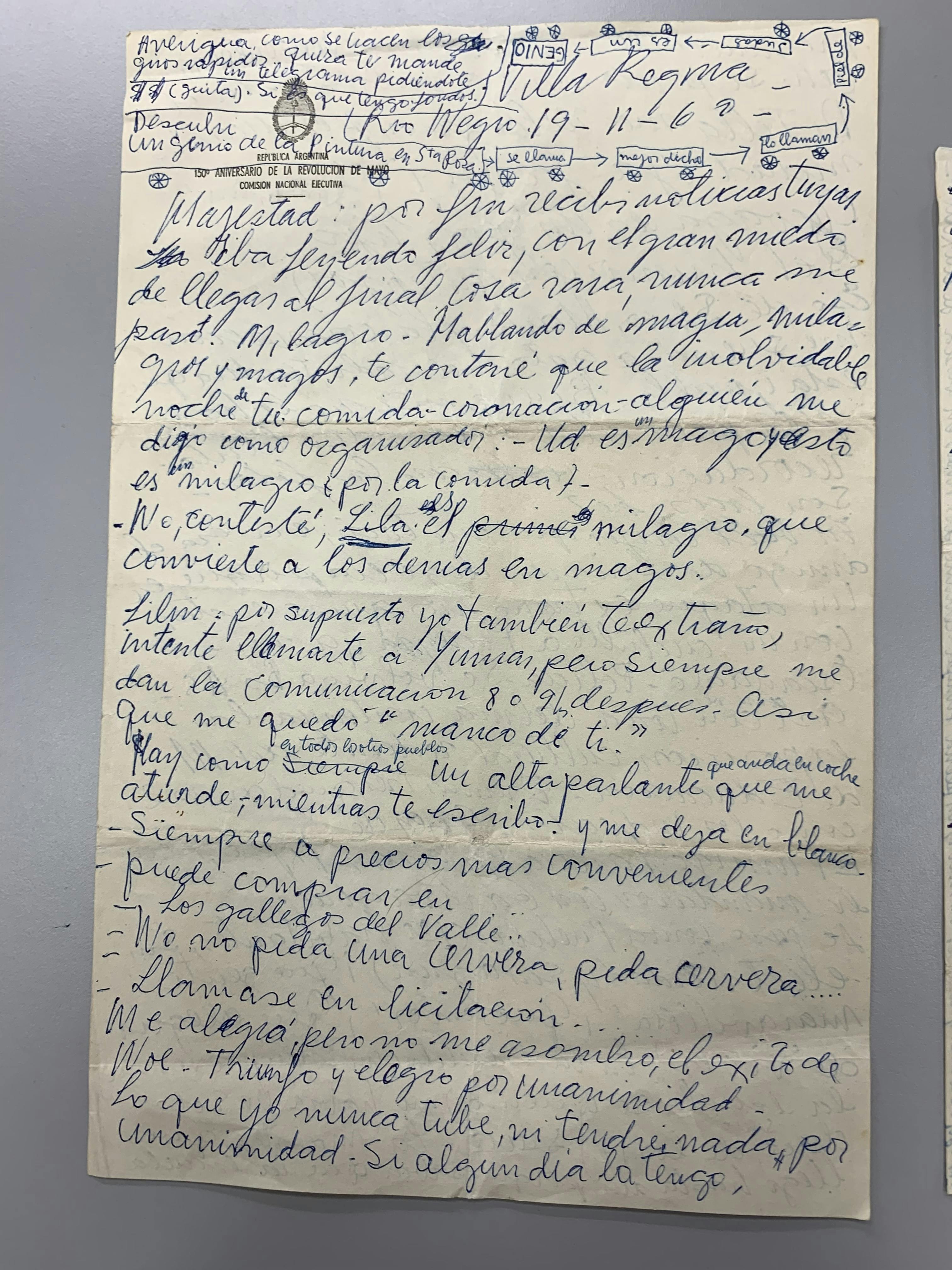

Fig. 1. Letter from Alberto Greco to Lila Mora y Araujo, sent from the Casariego House, 1962. Lila Mora y Araujo Archive. Centro de Estudios Espigas–Fundación Espigas Collection, Buenos Aires

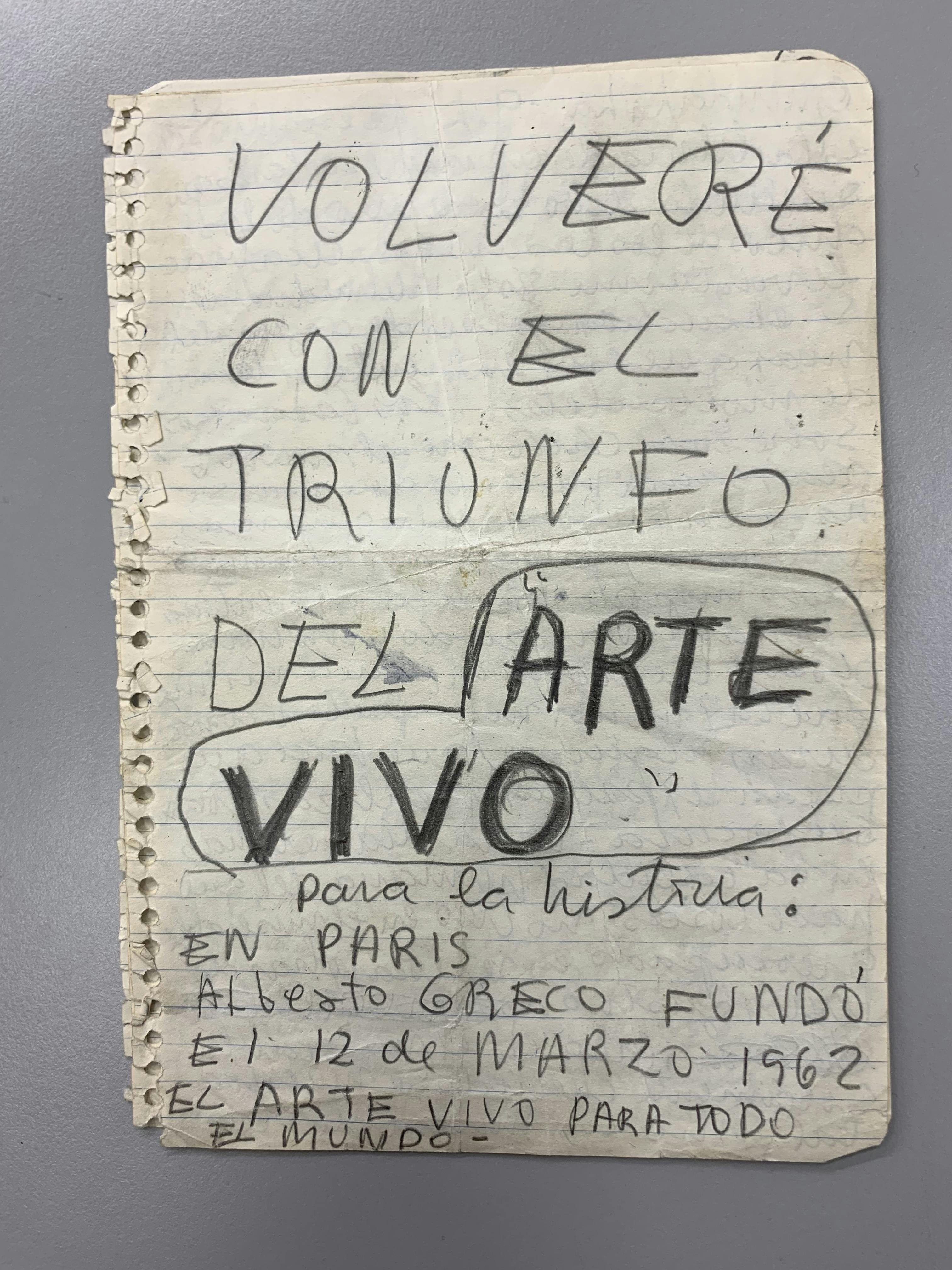

In 1962, Alberto Greco promised: “I will be back, with the victory of Arte Vivo.” And he declared: “For the history books: In Paris, on March 12, 1962, Alberto Greco founded Arte Vivo for the entire world” (fig. 1). 1

Maybe it was a prodigy performed by this magician that allowed me to discover, between Europe and Argentina, the clues to a possible genealogy for Alberto Greco’s Arte Vivo, which he later called “Vivo-Dito.” It was a one-person artistic movement that consisted of pointing to or surrounding a person, animal, or thing with a chalk circle and, with a gesture as spontaneous as it was definitive, turning it into a work of art. That is what Greco did on March 12, 1962, with his friend Alberto Heredia. “Vivo-Dito is, above all, the adventure of the real... it’s about an absolute and direct contact with things, places, people, creating unpredictable situations. It’s about showing and finding the object in its own space.” 2 Thus, the artwork material becomes the real; what the artist’s finger signals is life in itself.

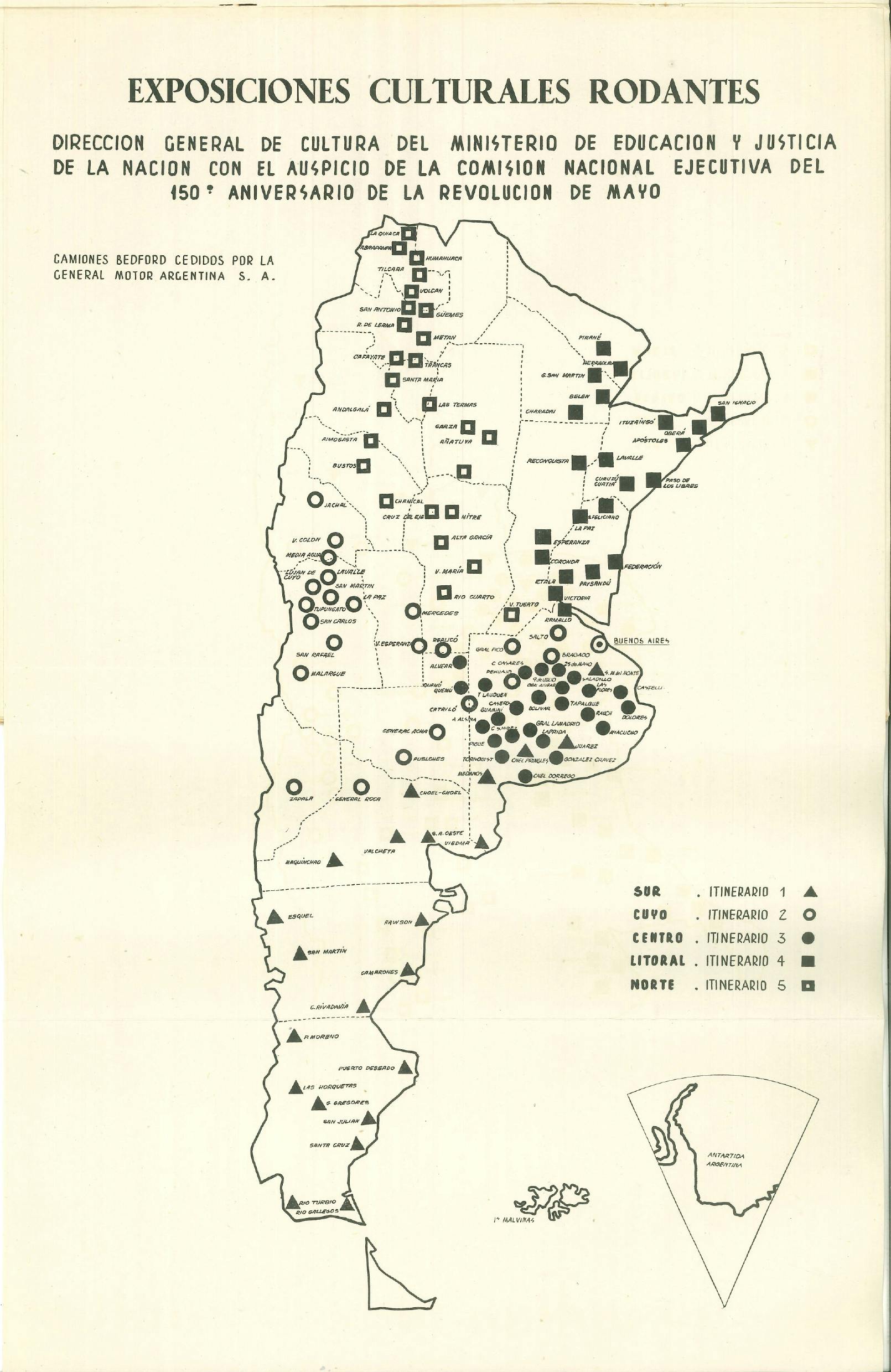

This essay aims to illustrate the experiences that shaped Greco's movement toward Arte Vivo. For that reason, we will focus on Greco’s participation in the Exposiciones Culturales Rodantes, or Traveling Cultural Exhibitions. The Traveling Cultural Exhibitions consisted of moving and exhibiting works of art throughout the Argentine territory, an effort that took place between October 1960 and February 1961. The essay will also focus on the letters exchanged between Greco and his friend Lila Mora y Araujo during that time, and the way in which a narrative is articulated through the testimony of the experiences that precede the Vivo-Dito.

“Don’t forget about the importance of Vivo-Dito’s art as a genuinely Latin American movement. I hope you also do something about it,” wrote Greco to Rafael Squirru, then director of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, in 1963. 3 Greco was aware of posterity, and of how important the art form that he launched was for his place of origin. He knew very well that his immediate audience would not understand the artist’s relevance until after his last work, which ended his life. “If you don’t do it, nobody else will. Of that, I can be sure. Since they are dead, they are irritated by any attitude of extreme vitality. Vital Vital Vital Vital,” he insisted categorically. 4

In the following episodes, we can glimpse the origin of this artistic experience, which condenses the intense timelessness of Greco’s work, which continues to attract public and critical attention. Greco’s work is also a crucial key for understanding contemporary art. The Vivo-Dito retrospectively illuminates some events in Greco’s life, which we consider as anticipations or prefigurations.

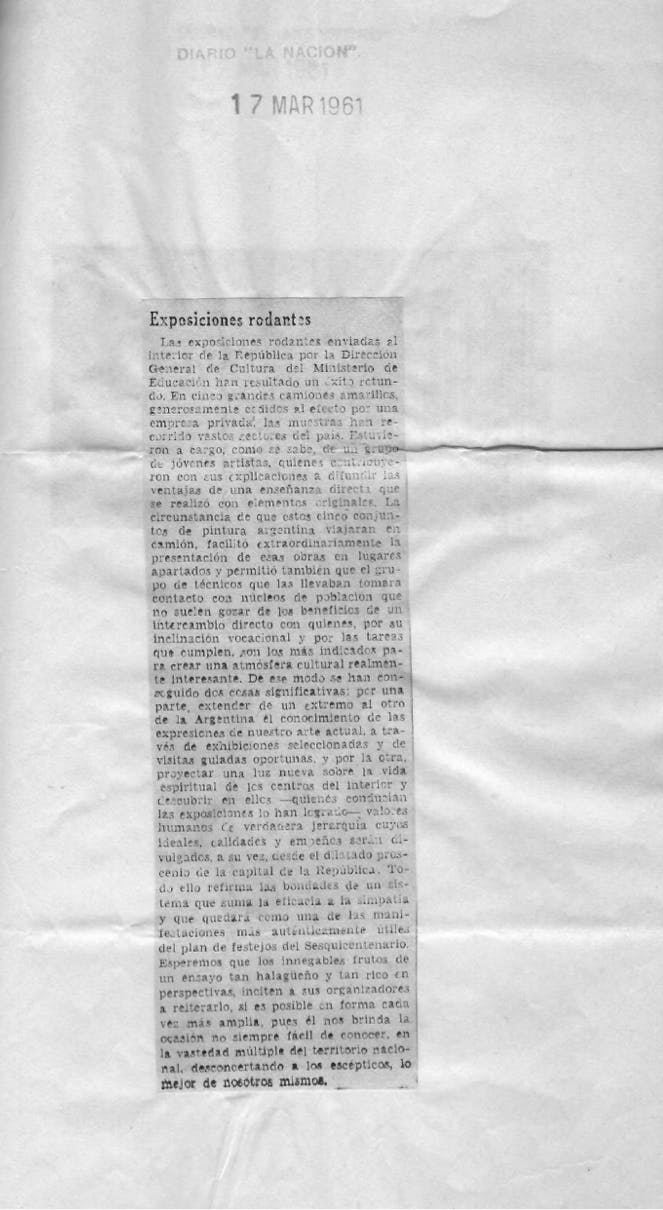

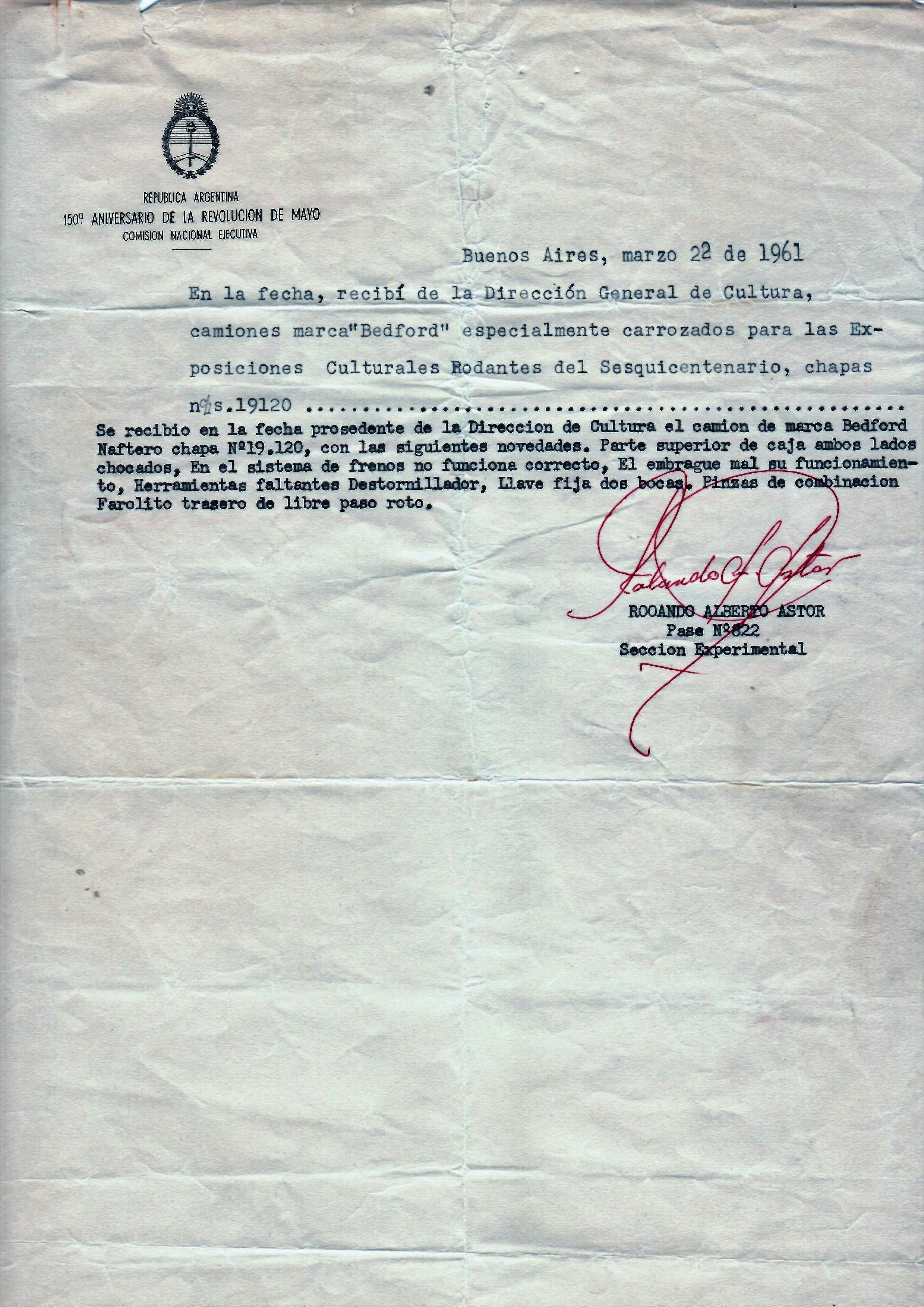

Fig. 2. Cover of the catalogue Ciento cincuenta años de arte argentino. Exposiciones Culturales Rodantes, edited by Alfredo Vitolo (Buenos Aires: Dirección General de Cultura del Ministerio de Educación y Justicia, 1961)

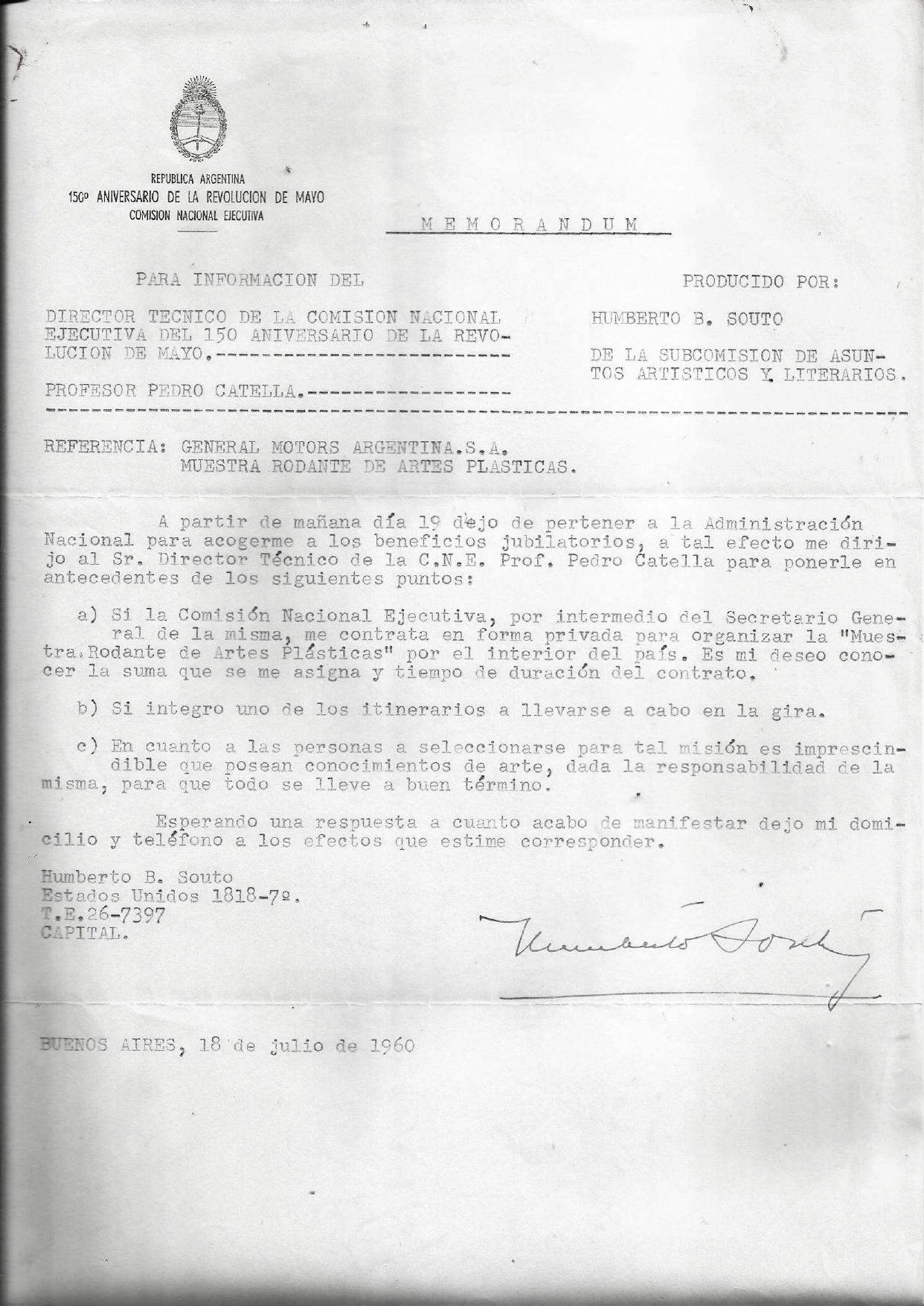

Fig. 3. Memorandum from Humberto Souto to General Motors Argentina, July 18, 1960. Traveling Cultural Exhibitions folders. Private collection

The Traveling Cultural Exhibitions were sponsored by the Cultural Office of the Secretary of Education and Justice of Argentina, and had been created by Rafael Squirru in 1960 for the 150th anniversary of the May Revolution, a crucial event for the Independence of Argentina, with the aim of transporting to all the country’s provinces the most representative of national art.

To understand Greco, it is crucial to take into account his urge to be in touch with people from whom he feels a vital energy, the communion between the work and the moment in which the artwork opens up to life. The Vivo-Dito is closer to an experience than to a performative action or a theatrical staging. Greco invokes an encounter that goes beyond representation. He does not interpret, nor does he place in the “fictional realm,” as David Lapoujade would say, 5 the image or the idea that a person or an object are different from themselves. Greco is, instead, the officiant of an action of a totally different order.

To analyze Greco’s leap toward this form of art making, it is necessary to dwell on his experience during the Traveling Cultural Exhibitions. These exhibitions were sponsored by the Cultural Office of the Secretary of Education and Justice of Argentina and had been created by Squirru for the 150th anniversary of the May Revolution, a crucial event for the Independence of Argentina (fig. 2). Five trucks left Buenos Aires in October 1960 with the aim of transporting to all the country’s provinces the most representative works of national art since the country was “free and independent,” with a program of exhibitions and other events that would be open to the public. 6

In May 2020, the archives for these exhibitions were found in Buenos Aires—five folders that compile manuscripts, photographs, and press clippings recording those great events. Accessing this material was crucial, as it revealed exactly which artists were involved and which itinerary, works, and trucks each one was in charge of.

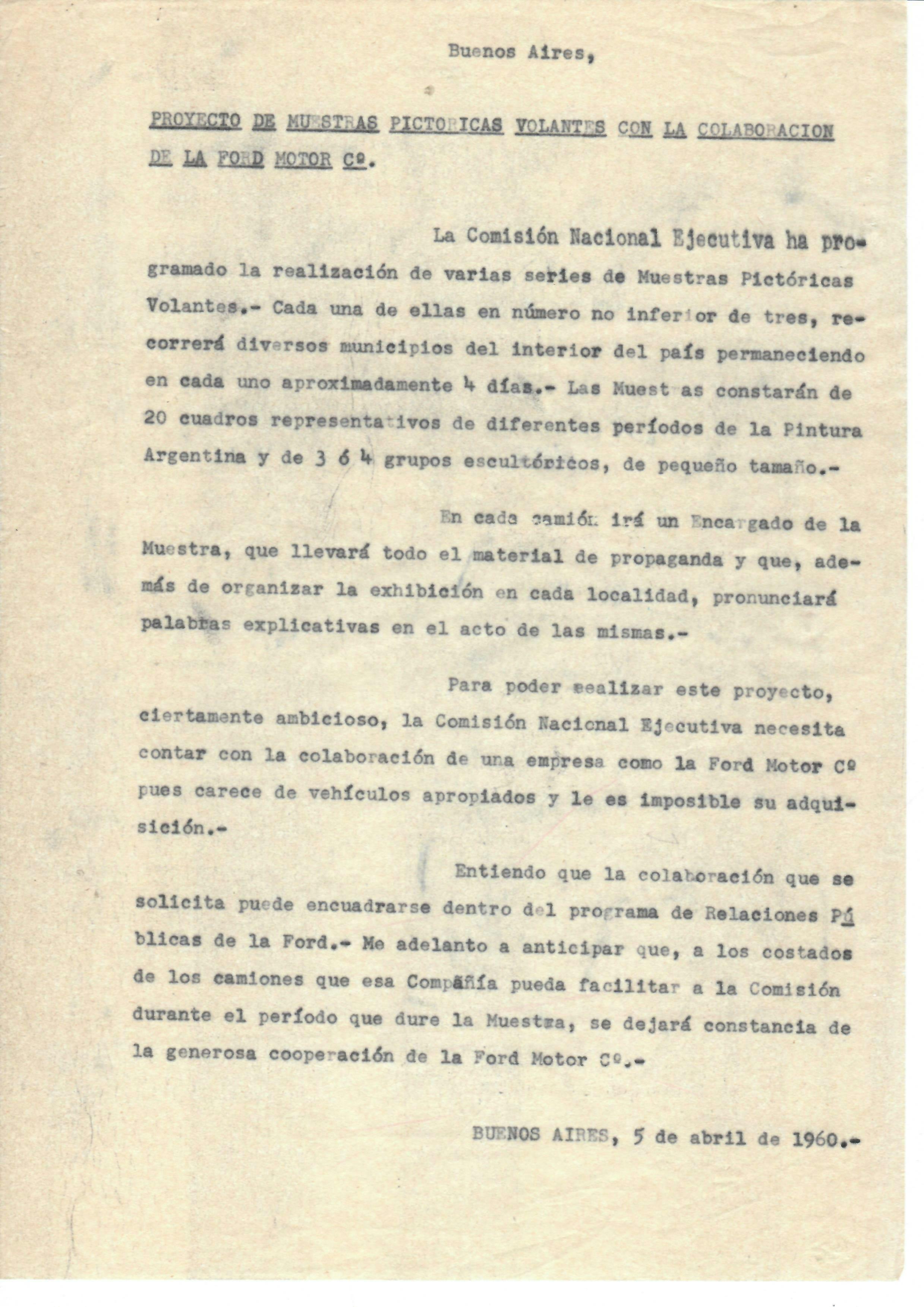

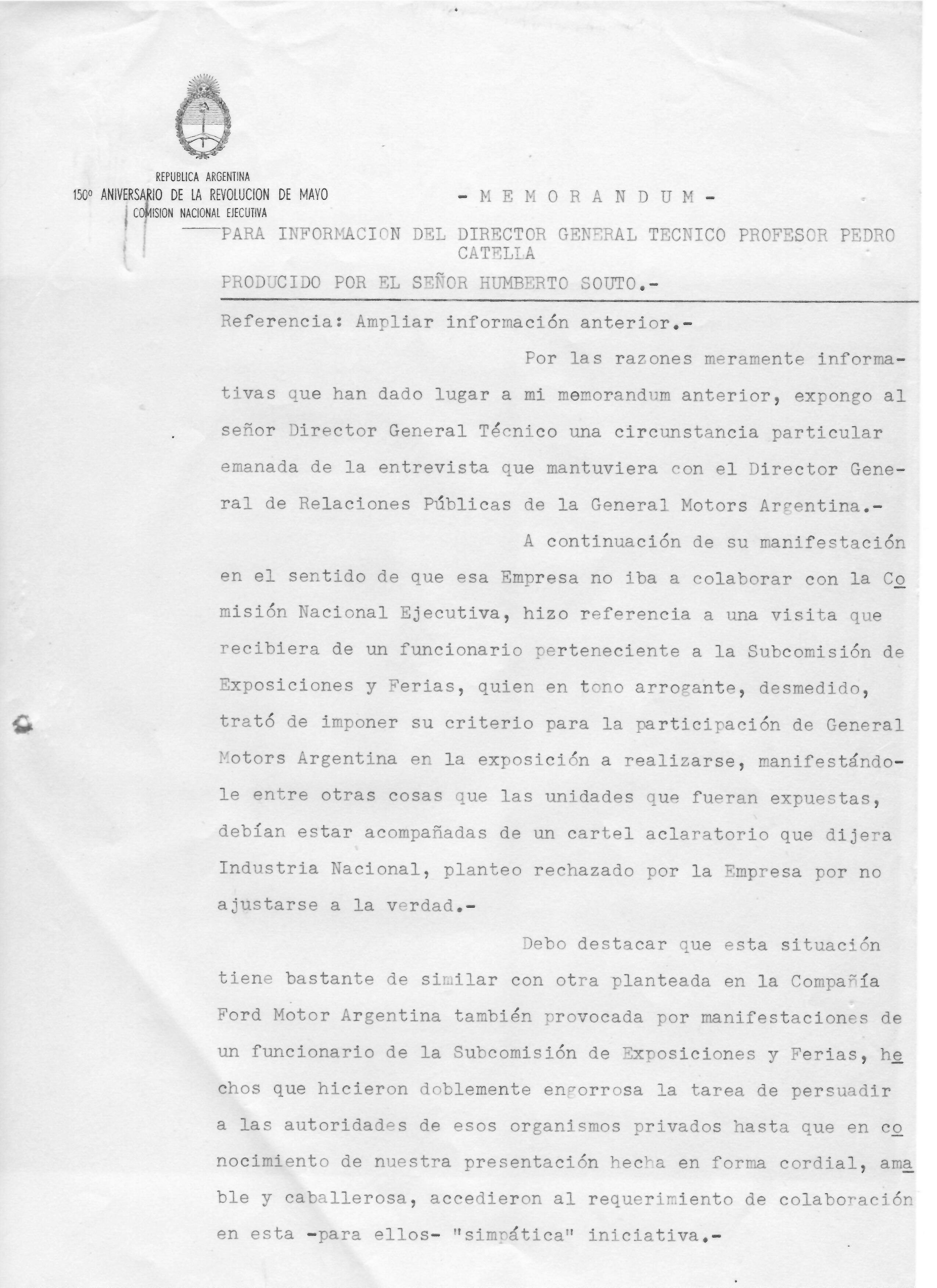

These documents add to existing historical information. Among the notes signed by Humberto Souto, who was in charge of the negotiation for the project’s launch, we can read: “With regards to the people to be selected for such a mission, it is essential that they are knowledgeable about art, given the responsibility of the endeavor, so that everything is carried out successfully” (fig. 3). 7 Rafael Squirru strove to “promote an environment in which creation was fostered… and the old consciousness was dynamited to make way for a new one.” 8 It is well known that Squirru’s vision allowed him to appreciate Greco’s art early on. He did not hesitate to recommend that Greco be part of this group of new artists that would be responsible for accompanying the five groups of artworks. The other four were Orlando Gianferro, Florencio Garavaglia, Josefina Zamudio, and Domingo Di Stéfano.

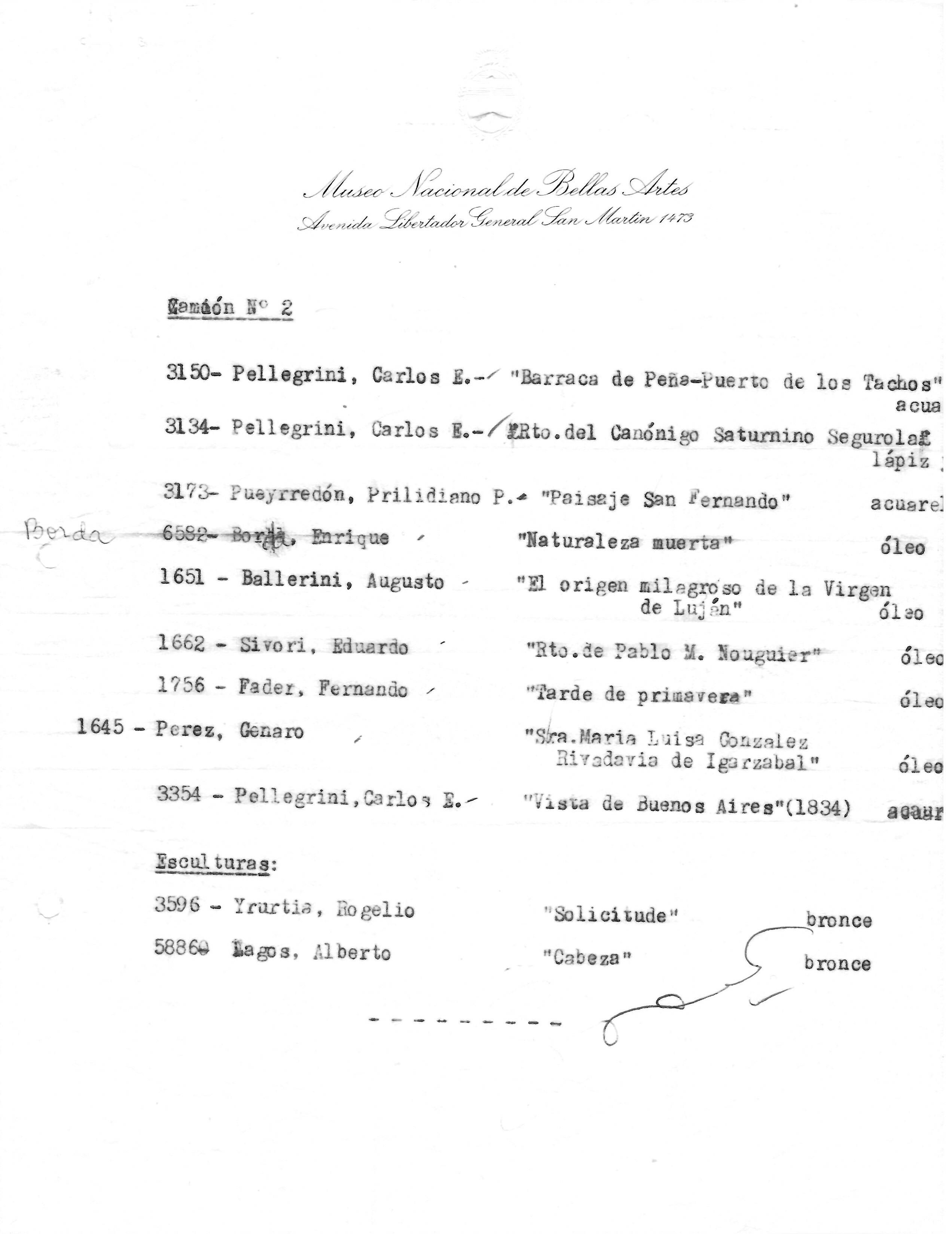

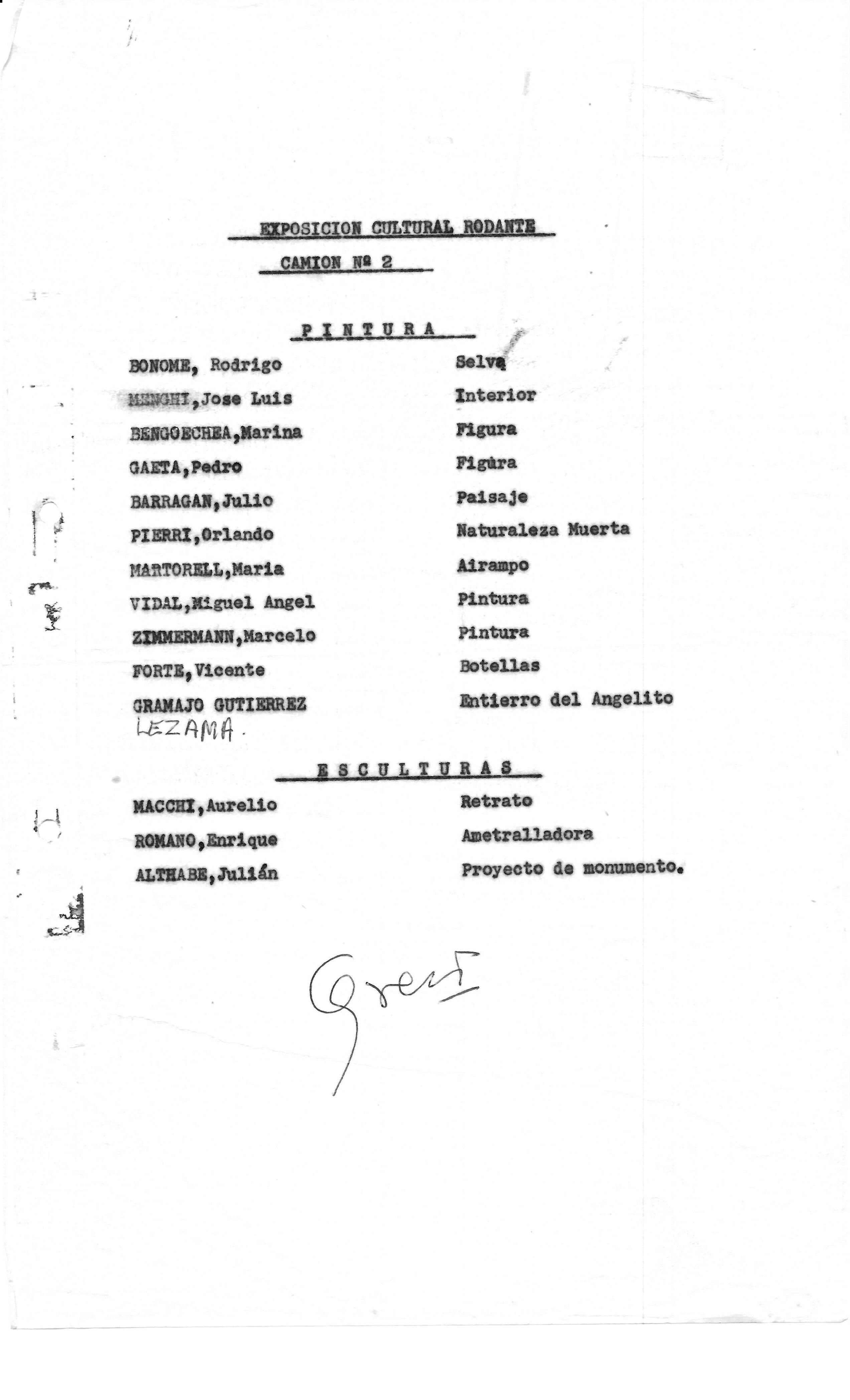

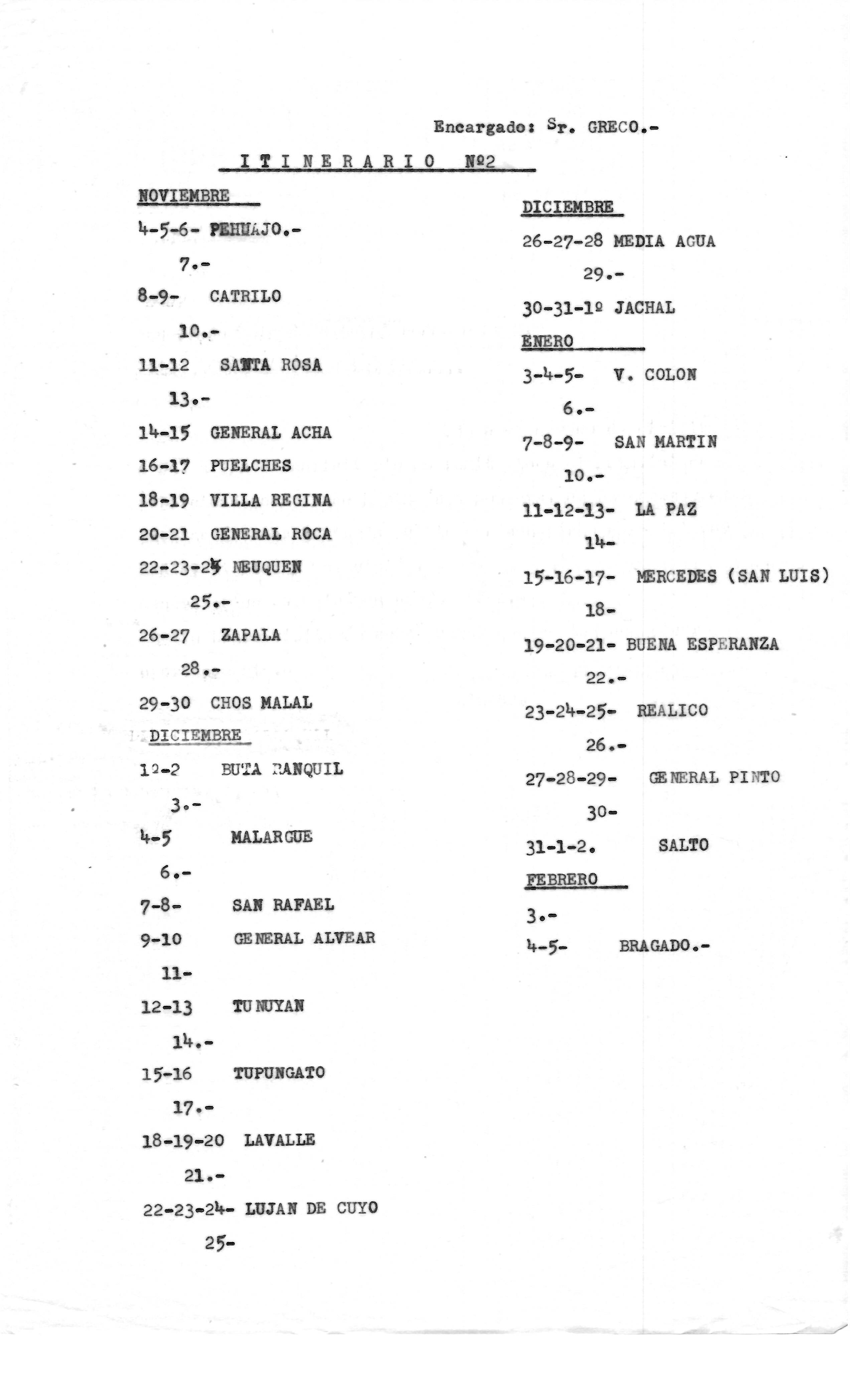

“The five trucks left Buenos Aires on October 29, 1960, at 11:30 a.m. They started from kilometer zero, in front of the Congress, the starting point of the Argentine highway network” (fig. 4). 9 For four months, the five artists traveled through Argentina in five different routes. The trips also included visits to neighboring countries such as Chile, Bolivia, and Brazil. It was a joint effort between the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes and the Museo de Arte Moderno, which made it possible to bring to regions completely remote from urban centers, throughout the country, “a panorama of the 150 years of the development of the national visual arts” (fig. 5). 10 The trucks, which had initially been called “volantes” (literally “flying”)—as stated in the memorandum addressed to Ford Motors, found in the archives—would have to visit a number of towns throughout the country, staying in each place for approximately four days and carrying twenty representative paintings from different periods of Argentine art, as well as small groups of sculptures. The aforementioned document also details that “in each truck there will be an Exhibition Manager, who will carry all the advertising material and who, in addition to organizing the exhibition in each location, will pronounce a few words at each opening” (fig. 6). 11

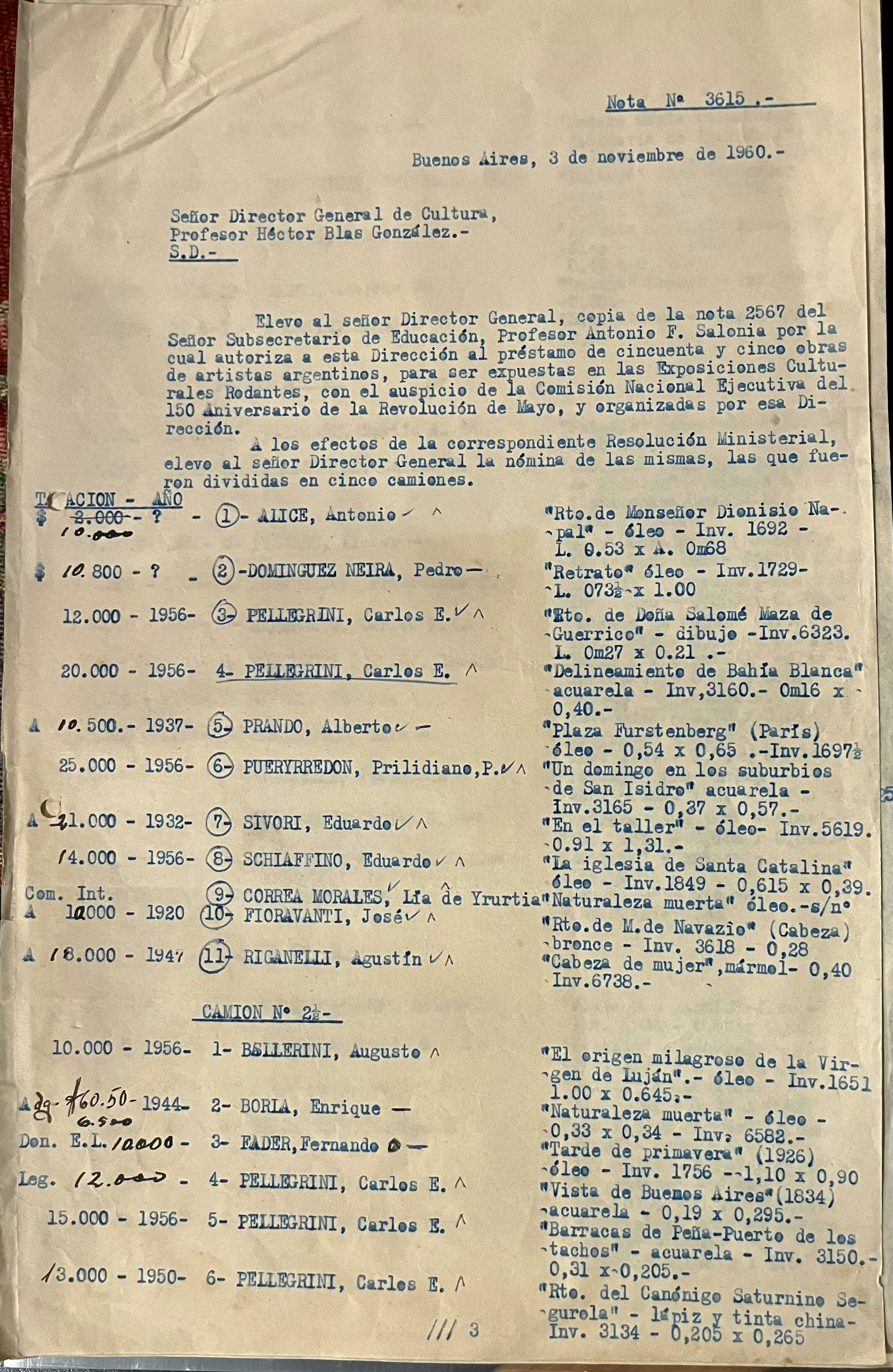

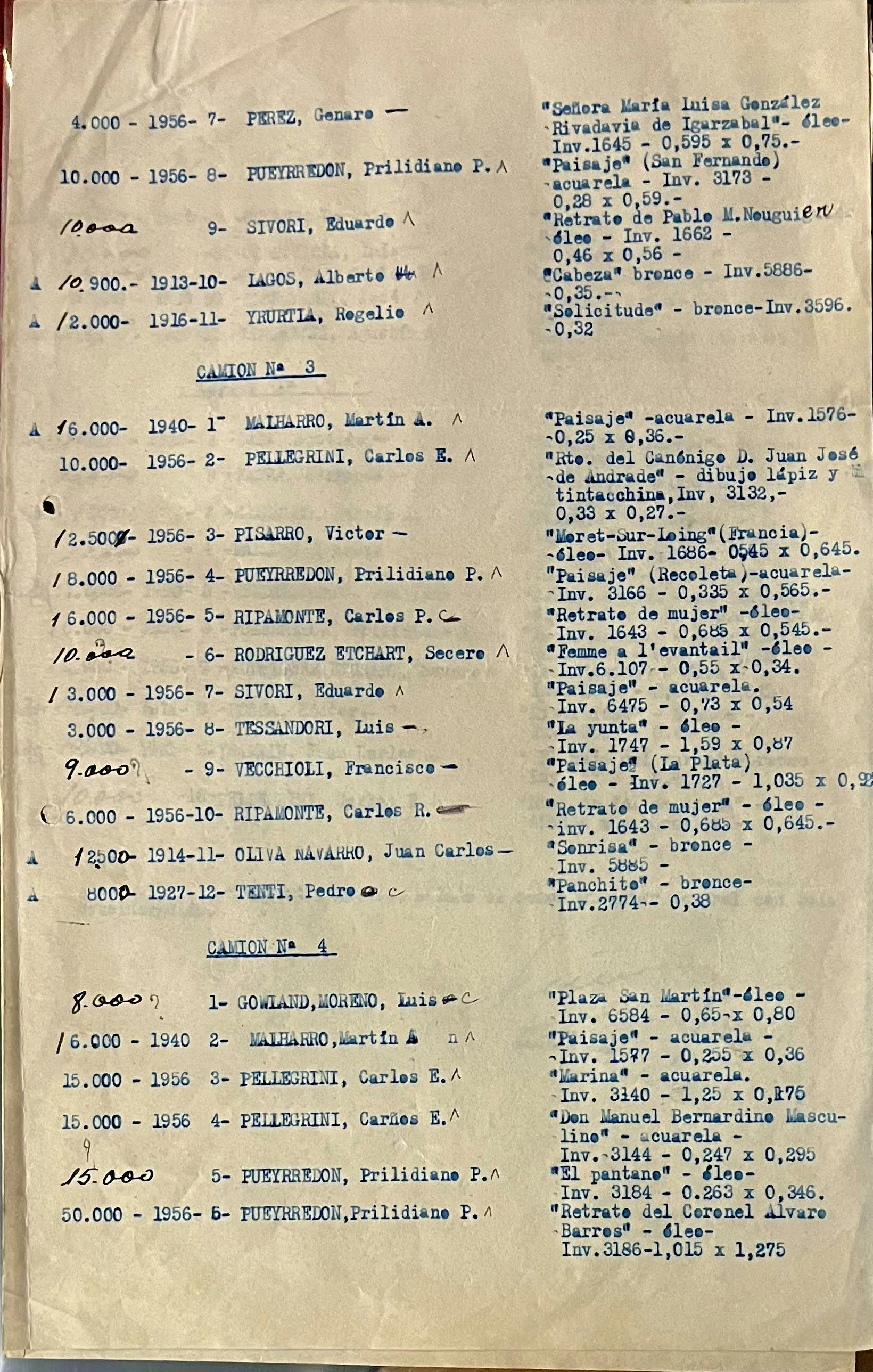

Fig. 7. i. Note no. 3615, November 3, 1960 (page 1). Traveling Cultural Exhibitions folders. Private collection

Fig. 7. ii. Note no. 3615 (page 2)

The event was exceptional. For the first time, important artworks from the national collection and some from private collections, both classical and contemporary pieces, left the institutions to be presented in clubs, libraries, squares, and streets.

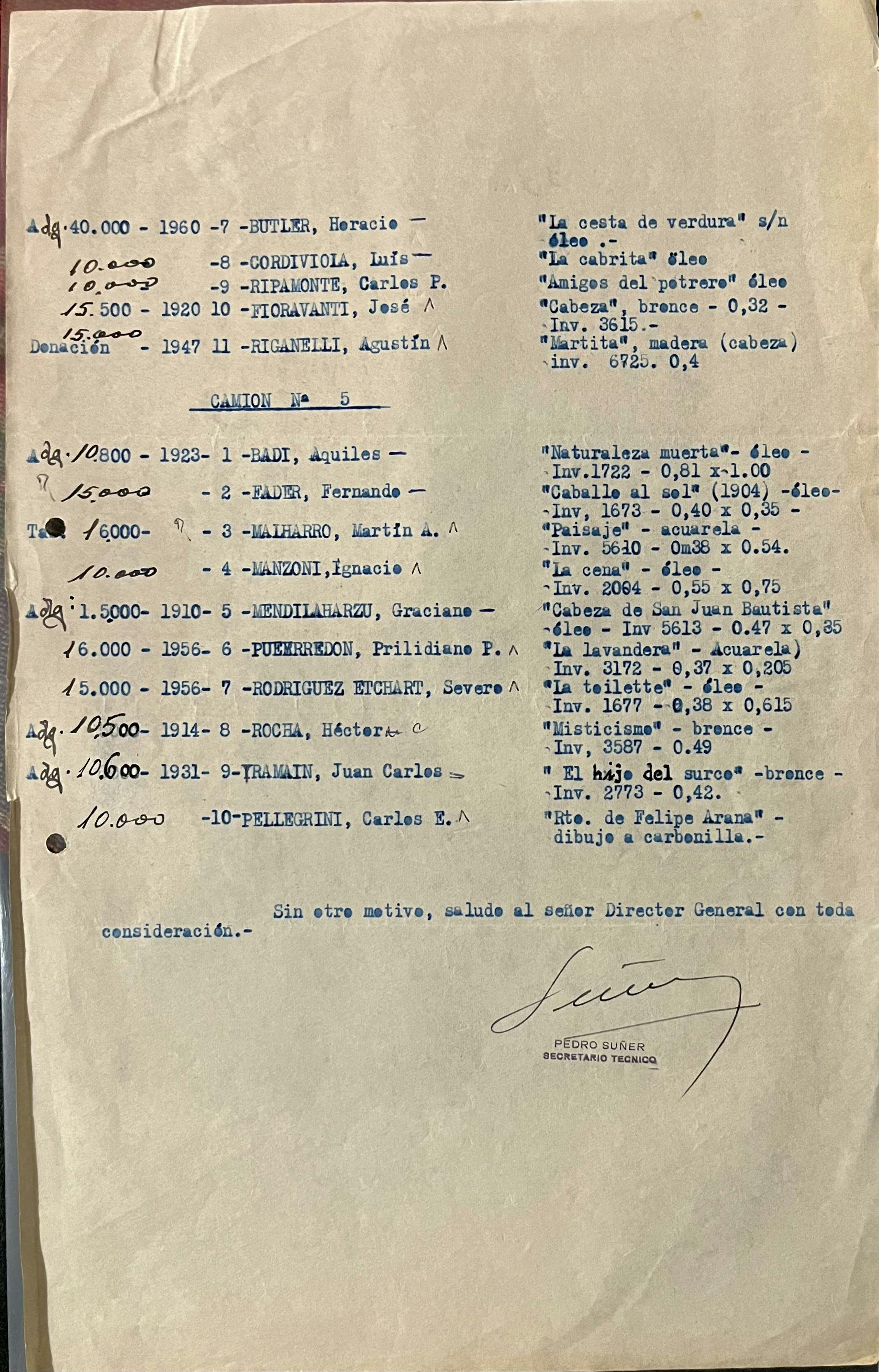

The event was exceptional. For the first time, important artworks of national heritage and some from private collections, both classical and contemporary pieces, left the institutions to be presented in clubs, libraries, squares, and streets. In a document signed by Professor Héctor Blas González we can see the authorization for the loan of fifty-five works by Argentine artists, the details of the works, and the figure of their value (fig. 7). 12 The selection includes works by Carlos Pellegrini, Prilidiano Pueyrredón, Eduardo Sívori, Lucio Correa Morales, Fernando Fader, Rogelio Yrurtia, Martín Malharro, Eduardo Schiaffino, Ángel Della Valle, and other similarly important artists. The goal was to encourage the habit of frequenting works of art and to showcase the various artistic movements in a didactic way.

Among the emblematic pieces of Argentine art history that were under Greco’s responsibility, we should mention Ernesto de la Cárcova’s Sin pan y sin trabajo (Without Bread and Without Work, 1894), also known as La huelga (The Strike). In addition to possessing an obvious technical quality (for which it was praised at the Exposición de Pintura y Escultura at the Ateneo de Buenos Aires in 1894), this painting was a breakthrough for the international art world when it was presented at the Saint Louis World Fair in 1904. 13 The characters in the painting are in a situation of striking poverty, surrounded by a dramatic atmosphere that underscores the difficulty of their circumstances, while looking through the window at a shuttered factory (fig. 8).

One can only wonder what the reception of this painting would have been like in the context in which Greco had the opportunity to present it. It is worth remembering that around 1958 Argentina was facing a difficult sociopolitical scenario. In the midst of the debate around Peronism, President Arturo Frondizi launched an economic stabilization plan that would greatly impact the Argentine population. In order to carry it out, Frondizi, with the support of the military, took repressive measures such as suspending all political and trade union activities.

Despite the complicated situation that institutions found themselves in at that time, Argentina was showing confidence in the cultural field, which was essential for strengthening democracy’s functioning through a sense of national identity. With a developmentalist spirit and the conviction that they were modernizing the country, Frondizi’s administration along with his advisor Rogelio J. Frigerio set in motion political changes that would have consequences in the cultural realm. The Traveling Exhibitions were part of a wider program of celebratory events, deployed on the occasion of the Sesquicentennial, which lasted throughout the year in different areas of the country. The program included patriotic celebrations and educational events, folkloric activities, sporting events, cultural activities, symposia, and international and national conferences. The magnitude of the effort and the resources made available to these projects were consistent with a public discourse intended to send a positive message to sectors of the country that were beginning to confront the government.

The ambitious project of the Traveling Exhibitions required adequate transport. Regarding the exchange for negotiations and sponsorships, the official catalogue states that “after unsuccessful attempts, [the project] was fortunate to find in General Motors Argentina the most favorable and friendly welcome.” 14 The automotive company decided to lend specially conditioned units of its recently produced Bedford truck (the first made in Argentina), in exchange for being advertised as a sponsor.

Even though Ford and General Motors rejected the proposal of local government officials to label as “Argentine industry” goods that were produced in US factories located in the country, 15 the manufacturing of the 1959 Bedford truck can be seen as the synthesis of the image the government sought to project for Argentina: a developed country that was part of the world stage. The truck thus became a kind of symbol that brought together all the ideas behind the Travel Exhibitions: national pride, a federal will, a developmentalist spirit, and the spreading of culture through an unprecedented and accessible museum format (fig. 9).

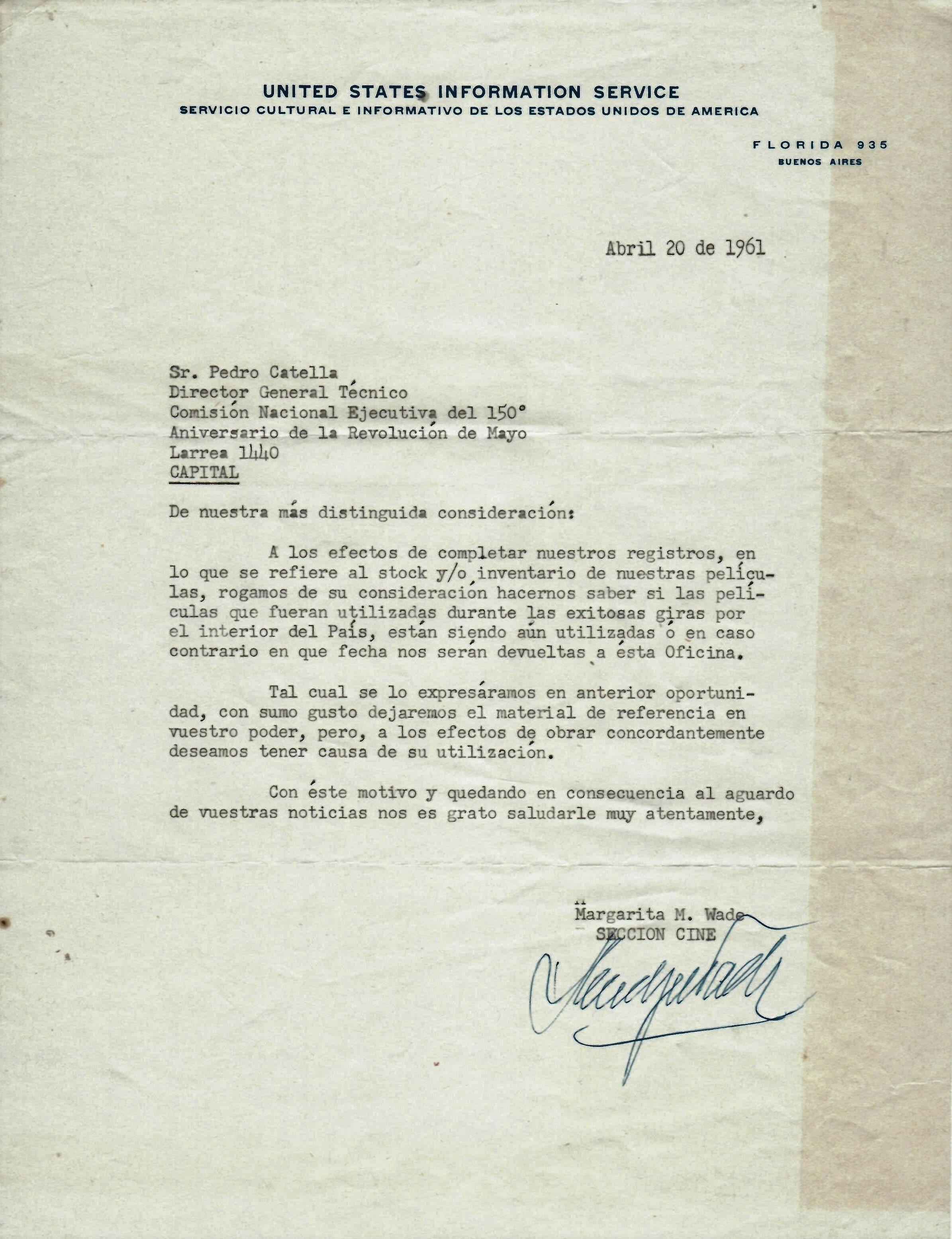

Fig. 10. Letter from Margarita Wade to the United States Information Service, April 20, 1961. Traveling Cultural Exhibitions folders. Private collection

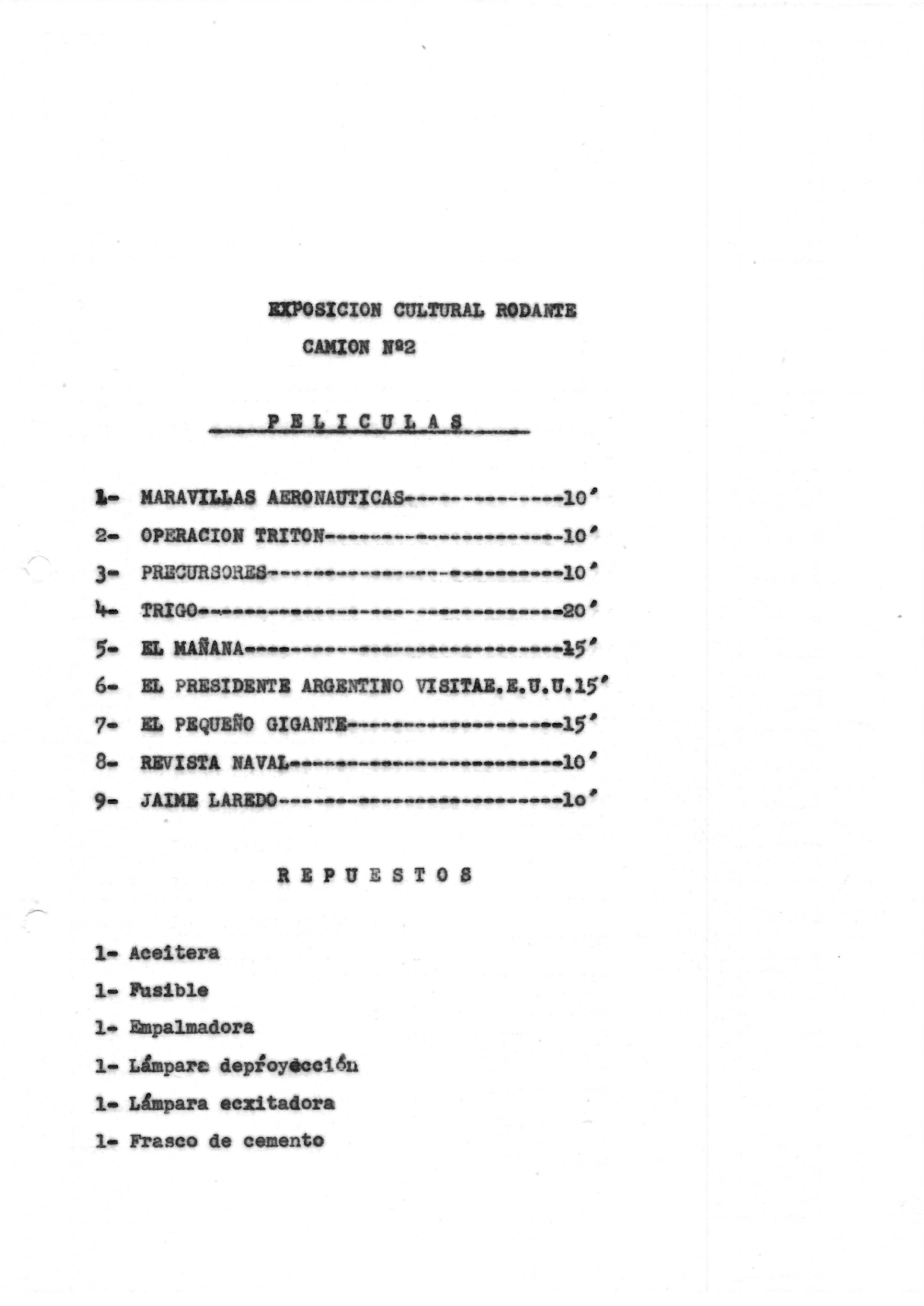

Fig. 11. Inventory of films and spare parts corresponding to itinerary #2, 1960. Traveling Cultural Exhibitions folders. Private collection

For most of the inhabitants of the provinces, the project was an important occasion to see original paintings and sculptures. This was a transforming experience for Alberto Greco, and an indispensable source for his art, as he repeatedly stated in his correspondence: “I live with the people. Only with them I feel like I’m breathing.”

Under the developmentalist model, economic growth was synonymous with industrialization. The government emphasized that Argentina should break its old economic model of exporting raw materials at low prices, thus promoting the protection of national industry and the creation of a strong domestic consumer market. Priority was given to oil production and the creation of an integrated road transport system that would lay the foundations for a local automobile industry. Foreign capital was considered essential to achieve this expected industrialization and relations with the United States were greatly strengthened during this period.

Among the documents in the Traveling Exhibitions archives, there is an agreement between the Argentine government and General Motors to screen films provided by the United States Information Service, including propaganda material (fig. 10). Among the list of film material that travels in Greco’s truck is a tape recording featuring Frondizi’s visit to the United States. At the time, the US was showing a growing interest in investing in the Latin American cultural field as part of a foreign policy that sought to expand its influence in the region vis-à-vis a possible Soviet advance, in the context of the Cold War (fig. 11).

All this is important for analyzing Greco’s participation in the Traveling Exhibitions. At a time that required resounding and extreme positions, Greco, daring and irreverent, cosmopolitan and ecumenical, processed his historical circumstance in his own way, moving between the interstices of official powers to produce his own aesthetic program, as he always did. “I AM AN AVANT-GARDE PAINTER… (ha ha ha!),” he wrote during the Traveling Exhibitions. 16

The activity represented an unprecedented modality of artistic dissemination for the local scene, a landmark event in the history of Argentine art. The young artists in charge of the traveling collection had to install and deinstall the works, and to bring them closer, through conferences, to populations “that do not usually enjoy the benefits of… a really interesting cultural atmosphere” (fig. 12). 17

For most of the inhabitants of the provinces, the project provided an important opportunity to see original paintings and sculptures. This was a transformative experience for Greco, as he repeatedly stated in his correspondence. Thanks to this journey to towns in Buenos Aires, La Pampa, and the Cuyo region, he was able to be in direct contact with people. This was an indispensable source of inspiration for his art, as evidenced by one of his statements: “I live with the people. Only with them do I feel like I’m breathing.” 18

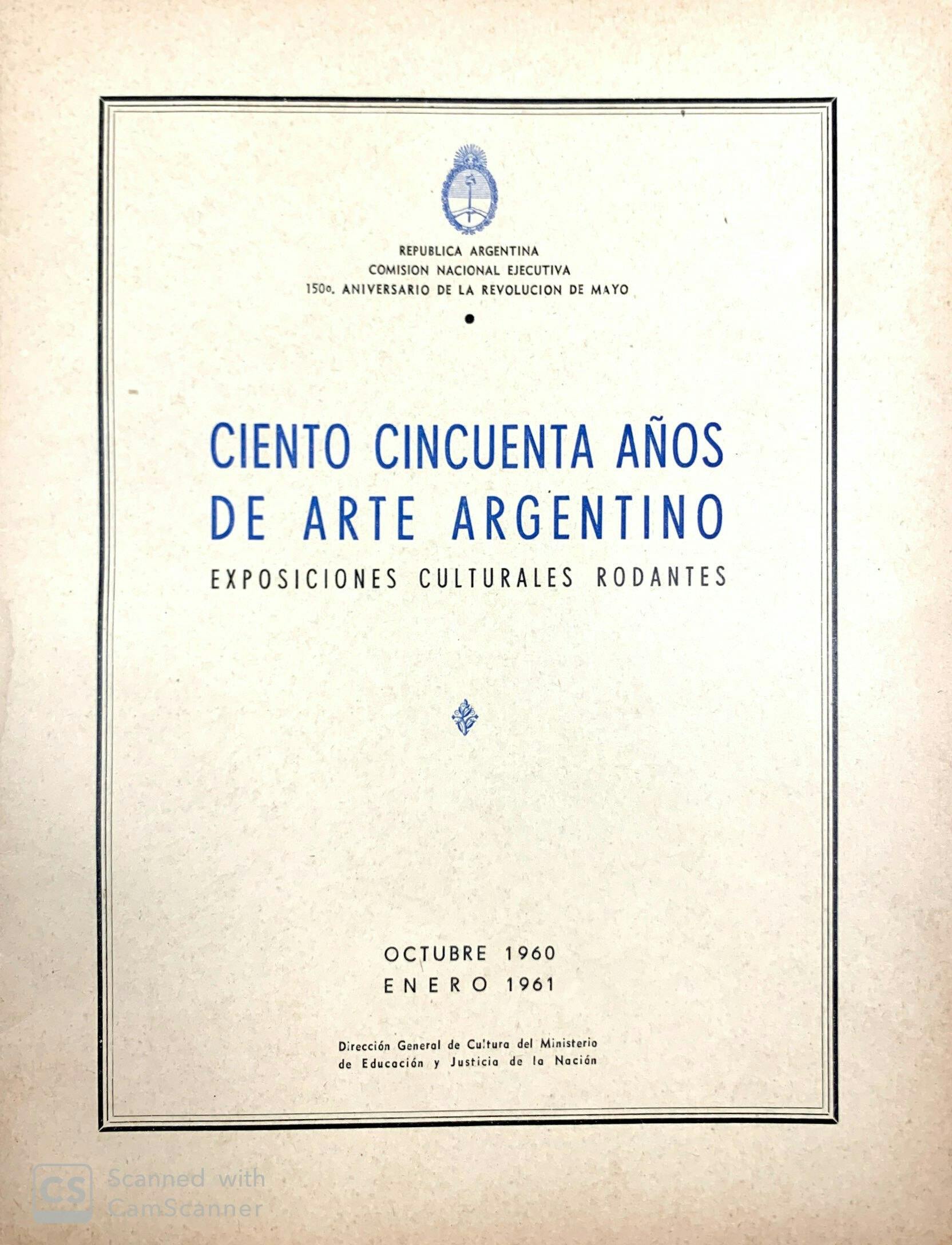

In light of the archives, the known records of the Vivo-Dito actions carried out between 1962 and 1965 (photographs, statements, manifestos, letters, manuscripts), acquire new dimensions. The records of the organization and development of the Traveling Exhibitions and the details of the tasks that were assigned to Alberto Greco illuminate the sociocultural and political situation of Argentina, the decisions about the works that traveled, which pieces were considered artistically representative and how they were distributed for each itinerary, as well as issues of logistics, such as the resolutions that determined routes, and even specific details of the condition of the trucks upon their return (fig. 13 and fig. 14).All this, together with an anonymous writing found in folder no. 2 corresponding to Greco’s itinerary, completes an image of Greco’s presence in this process.

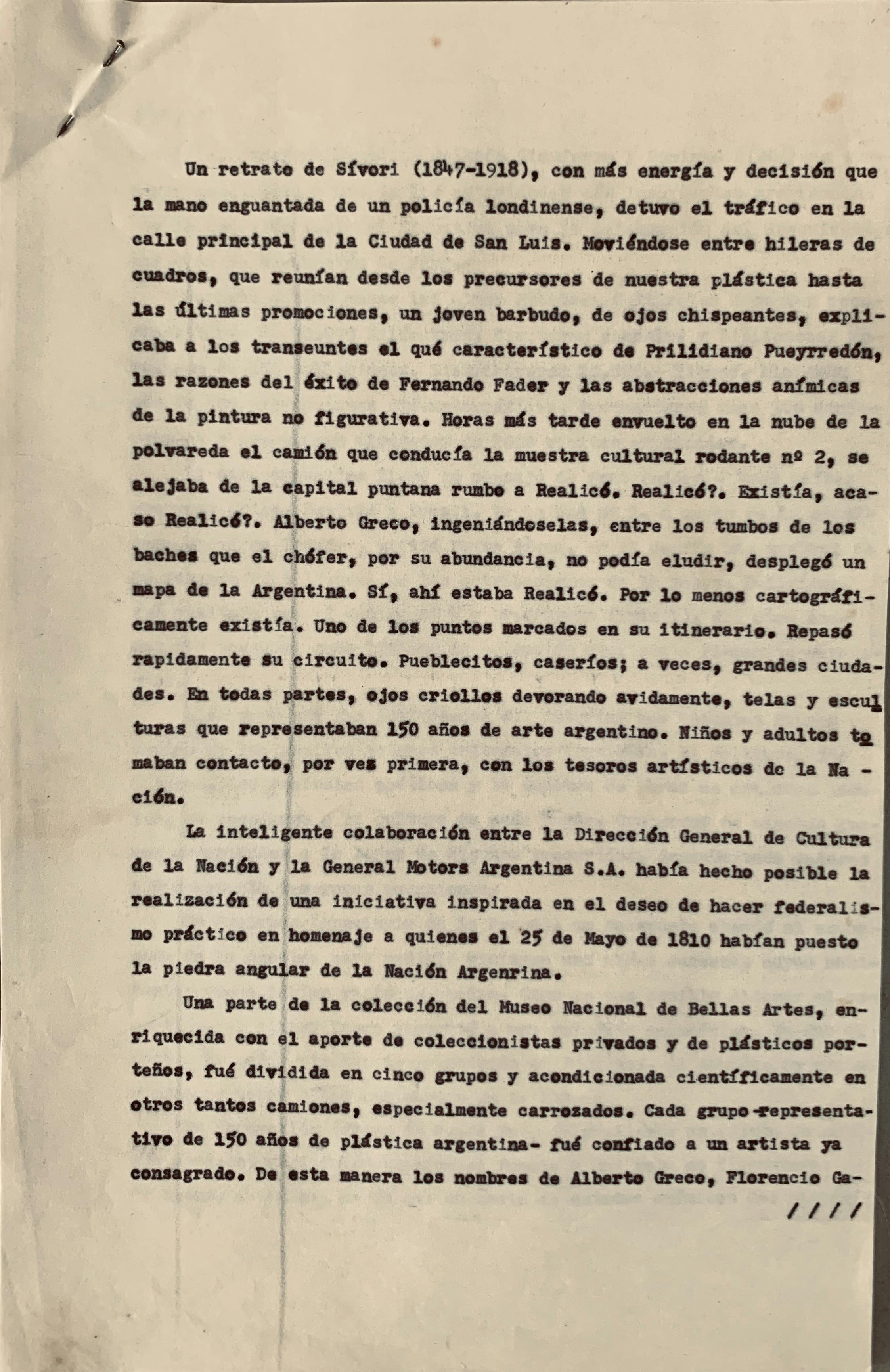

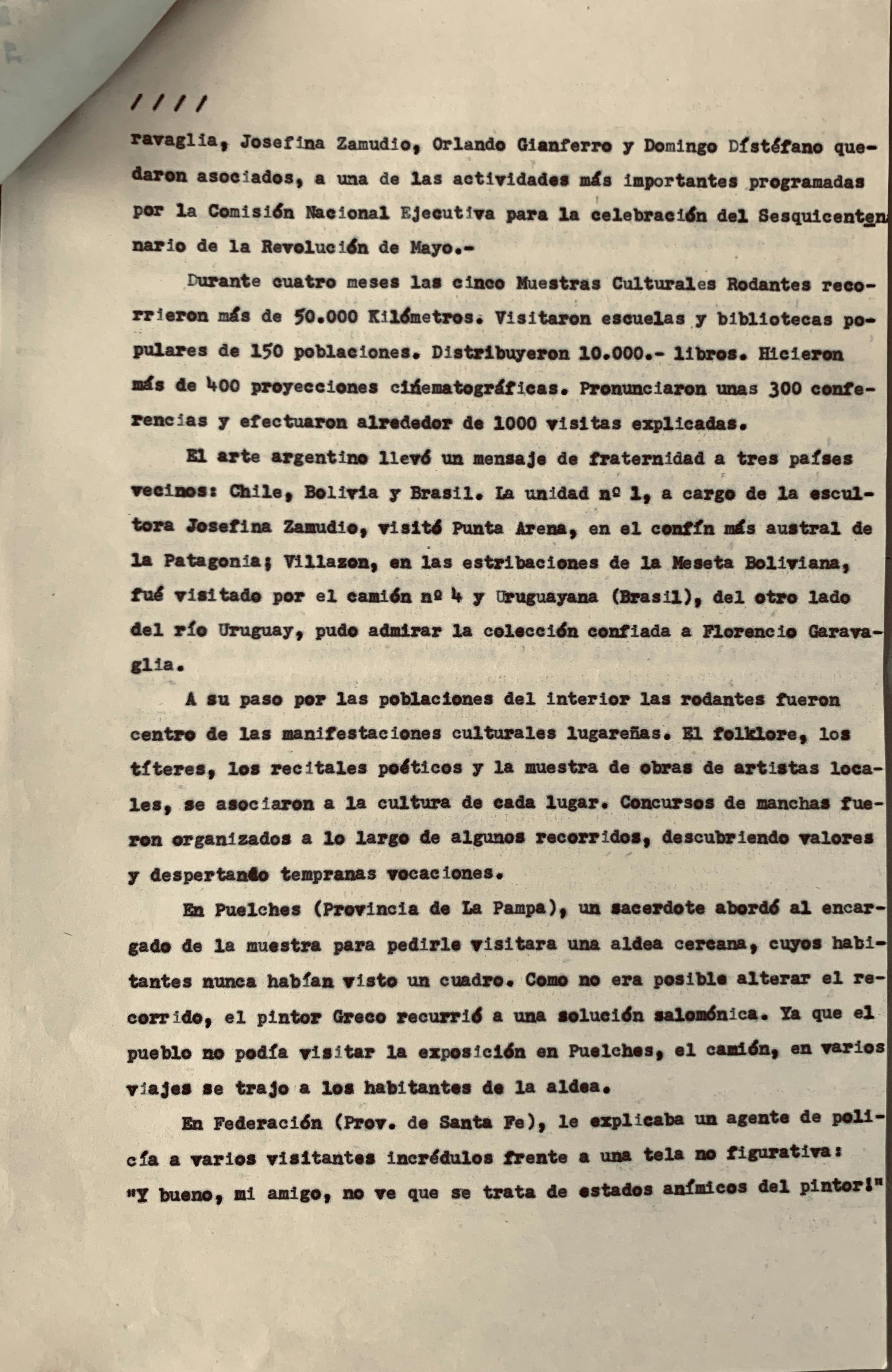

Fig. 15. i. Anonymous writing. Typed (n° 1). Travelling Cultural Exhibitions archive. Private collection. 23,5 x 34, 5 cm.

Fig. 15. ii. Reseña anónima de las Exposiciones Culturales Rodantes (página 2)

Fig. 15. iii. Anonymous writing. Typed (n° 3). Travelling Cultural Exhibitions archive. Private collection. 23,5 x 34, 5 cm.

Fig. 16. Alberto Greco standing next to a Bedford truck. Lila Mora y Araujo Archive. Centro de Estudios Espigas–Fundación Espigas Collection

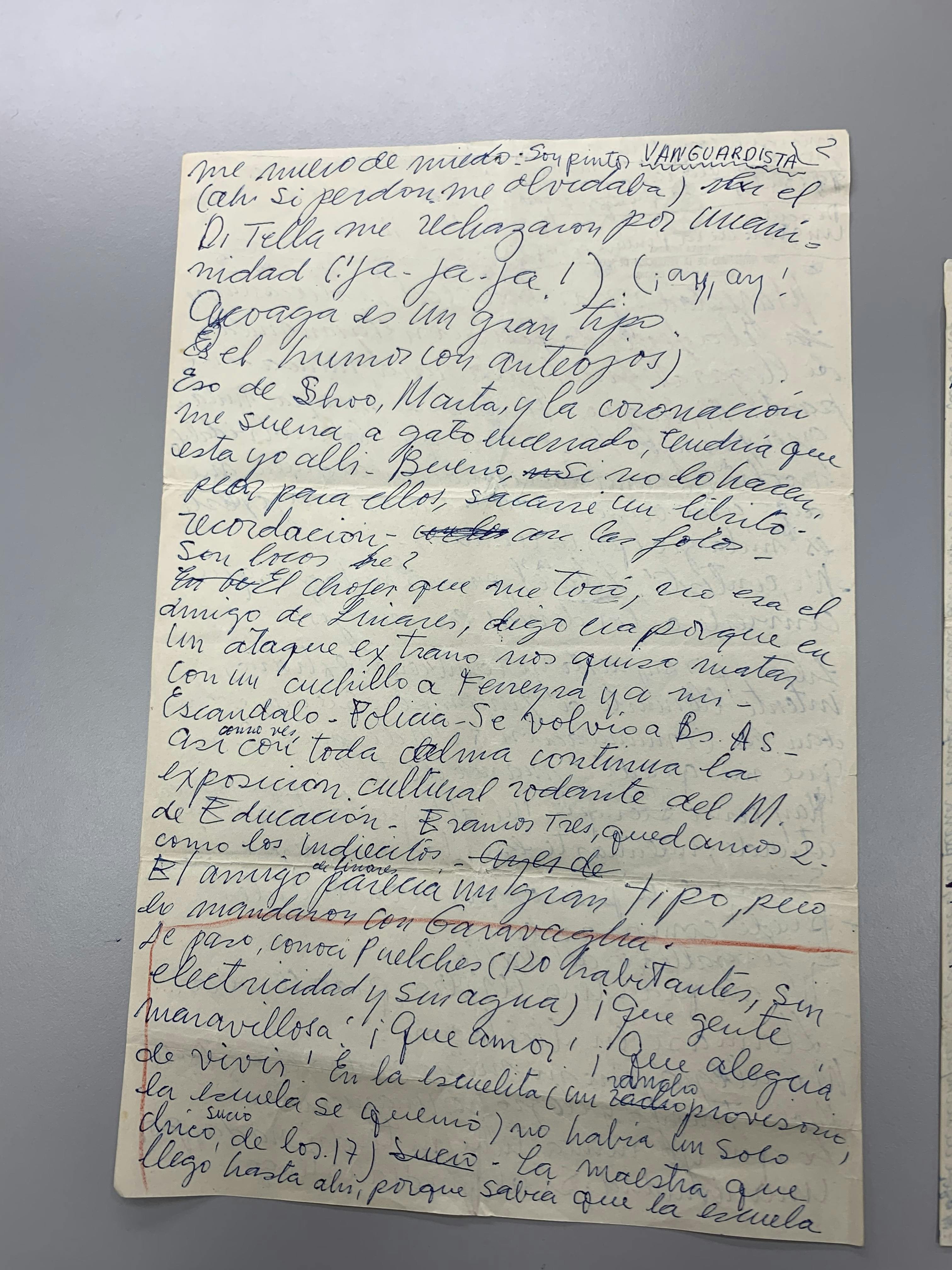

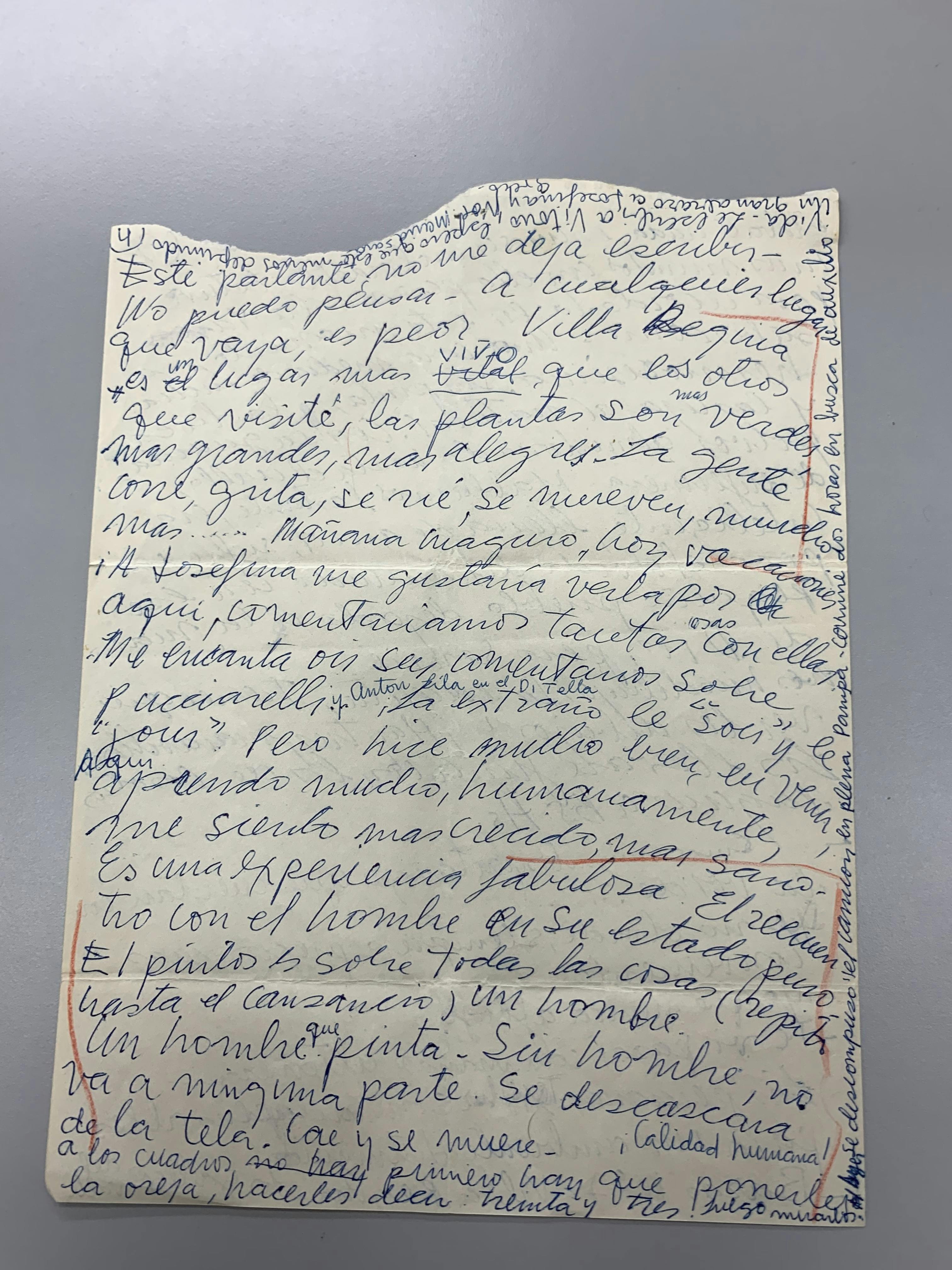

Fig. 17. i. Letter from Alberto Greco to Lila Mora y Araujo, November 19, 1960 (page 1). Lila Mora y Araujo Archive. Centro de Estudios Espigas–Fundación Espigas Collection

Fig. 17. ii. Letter from Alberto Greco to Lila Mora y Araujo, November 19, 1960 (page 2)

Fig. 17. iii. Letter from Alberto Greco to Lila Mora y Araujo, November 19, 1960 (page 3)

Fig. 17. iv. Letter from Alberto Greco to Lila Mora y Araujo, November 19, 1960 (page 4)

The atmosphere during those years, in which the country was going through a process of developmentalist transformation, a cultural effervescence dominated by a spirit of agitation, and a great voracity for new ideas, was a great stimulus and a propitious environment for innovative creation and the human warmth that Greco so longed for when he was in Europe.

As in everything that concerns Greco, a magical aura is present in this writing, which consists of three typewritten pages, unsigned and undated, with a very “Grecian” chronicle that places him once again in the center of the scene and offers us the missing images of his fabulous informality in La Pampa, near Realicó, a town that is considered the geographical center of the republic:

"A portrait of Sívori (1847–1918), with more energy and determination than the gloved hand of a London policeman, stopped traffic on the main street of the city of San Luis. Moving between rows of paintings, which included everything from the forerunners of our art to the latest cohorts, a bearded young man with sparkling eyes explained to passersby what is characteristic of Prilidiano Pueyrredón, the reasons for Fernando Fader’s success, and the psychic abstractions of non-figurative painting. Hours later, wrapped in dust, the truck that was driving the traveling cultural exhibition no. 2 was moving away from the capital of San Luis toward Realicó. Realicó? Did Realicó really exist? Alberto Greco, between the bumps of the abundant potholes that the driver could not avoid, managed to unfold a map of Argentina. Yes, Realicó was there. It existed—at least on the map. It was one of the stops on the itinerary. He quickly went over it. Tiny towns, homesteads; some cities. Everywhere, there would be local eyes avidly devouring canvases and sculptures that represented one hundred and fifty years of Argentine art. Children and adults made contact, for the first time, with the artistic treasures of the nation.

In Puelches, La Pampa Province, a priest approached the person in charge of the exhibition and asked him to visit a nearby village whose inhabitants had never seen a painting before. Since it was not possible to alter the route, Greco, the painter, resorted to a Solomonic solution. Since the town could not visit the exhibition in Puelches, the truck brought the inhabitants of the village in several trips (fig. 15)." 19

This is how Alberto Greco appears in his journeys into remote territories of the country, approaching people, and life, in a peculiar way, in the most forgotten places, producing the contagion that he always generated. Although no photograph or manifesto has been found as a record, unlike the case of his actions in Piedralaves (1963), this story leaves a clear image of a moment that would be revealing for Greco and his way of understanding art and life, which for him are one thing.

This trip around the country would allow him contact with the “human material” in the breadth of the Argentine landscape, enhancing the singularity of his creative energy. These would be moments of shimmering reality when, as we will see in his correspondence, he appears at the same time as a teacher and as an apprentice, and in which his began to think about art’s existence as a mission, which would be defining for his subsequent work. “Being in contact with the townspeople fills Greco with joy. Amongst the people, he is more than comfortable, he is in his element. In the numerous letters that he writes to Lila Mora, he speaks many times with enthusiasm about what he describes as ‘human material’.” 20

In a photograph from the archive of his great friend and protector Lila Mora y Araujo (1909–2004), Greco can be seen in front of the truck that took him on his journey. As the press clippings indicate, the vehicle (with plate number 19120) was a yellow Bedford, featuring the sponsors’ logos. In the image, Alberto Greco can be seen resting on the edge of a road on a clear summer night, pensive, with his hands in his pockets. It seems that he is stretching his legs out after a long journey. This document is the only photographic record of Greco in the Traveling Exhibitions (fig. 16).

Days before the beginning of the trip (which began on October 28, 1960) Greco had organized an event to express affection for Mora and Araujo in a Buenos Aires restaurant. He had seen her in a sad mood, and decided to organize a large dinner party so she could have fun with friends. In the homage, Greco designated her with the title of “Her Majesty,” and gave her a crown that he had made with nails. On October 30, he set off in one of the trucks, and throughout the trip he kept in touch with his pen pal. In these letters, which Mora y Araujo kept carefully, Greco moves from the autobiographical story to the manifesto, from gossip to conversation. Greco was always careful to mention everything that was presented to him (he transcribes an invasive radio advertisement as if it were a loudspeaker) and, among his informal comments, scattered throughout the profuse writing are reflections that anticipate what would become his aesthetic medium. As César Aira suggests: “the artist leaves… available to whomever wants to use it the story of his approach to the general system of the arts. The work begins the infinite path of its completion.” 21

Throughout his correspondence, Greco tells Mora and Araujo about his work as “team leader,” which he performs “perfectly,” having “no problems with the staff.” In a letter from Pehuajó, on November 7, 1960, he writes: “You cannot imagine the order and perfection with which I prepare and do things. Suffice it to tell you that I am the first to get up in the morning (8 a.m.). A lot of people came to the exhibition. I think traveling exhibitions are a wonderful idea. Wonderful things can be done. I plan to give two lectures at each stop (I’ve already prepared them). One will be about painting in general and the other about man and current painting.” 22

Days later, from Santa Teresa, La Pampa, Greco told Mora and Araujo that in Catriló they put on an exhibition at the Círculo Italiano and that they organized a painting contest with four hundred children. In his letter, Greco equates himself with great figures of the culture of the moment: “I, the painter from the outside, pointed him out as a great painter for the future. (I am at the same time [Guido] Di Tella and [Lionello] Venturi). It was the first painting exhibition that was held in that place. The guys wrote fabulous things in the signing album that would make you happy. You’ll see them when I come back… The owner of the movie theater told me: I am forty-three years old, and this is the first art exhibition that I have seen here. The awards ceremony was wonderful (unforgettable). I’m excited. There is fabulous human material. A lot of things can be done.” 23

At the beginning of the transcribed paragraph, we added italics to highlight a word that would be key for the Vivo-Dito: to point out. As Francisco Rivas said: “In the letters to Lila, there are clear insights into the future of his work.” 24

Later, Greco sends her another letter from Villa Regina in which he looks back and, analogously to the “rear-view mirror” of the truck in which he travels, he reviews that night of the “Coronation,” when he acted as a “Magician” and designated Mora and Araujo as “Her Majesty.” At the same time, he recounts his experience with the people of the places he visits and places himself at the center of the scene, this time as the “genius of painting.” He then adds, as in a crime story, that the driver had tried to stab him and his assistant in a confusing episode: “Scandal-Police-He returned to Bueno Aires. As you can see, the Traveling Cultural Exhibition of the Ministry of Education continues. We were three, now we’re two. Like the little Indians” (fig. 17). 25

There, in the enormous space of the Argentine landscape, in the middle of the dust cloud, Greco affirms, we claim the concept of the “living”: that which lives in the direct apprehension of the real and which, together with his inner experience, he will then point out through his living finger in the Vivo-Dito. In 1964 he would describe it as: “what is pointed to with the finger, what is shown, what happens.” 26 The expansion of art into life, which is also an expansion of the aesthetic field, can be observed in the original manuscript of that same letter, in an important detail: Greco crosses out the word “vital,” and adds in capital letters “VIVO” (alive): Villa Regina is a more vital VIVO place than the others I visited, the plants are greener, bigger, happier.” 27

In Villa Regina, something happens to Greco: as Squirru, the promoter of Informalismo, said, the movement’s adventure lies in lived experience. 28 Every Informalist work is born out of the living: lived experiences that express an essential adventure of human spirit. This is what Greco wants to discuss in his letters: “People run, shout, laugh, move a lot more… But it was really good for me to come here. I learn a lot from a human point of view, I feel more grown up, healthier. It is a fabulous experience. The reunion of man in his pure state.” 29 Greco feels captivated by the poetry of the atmosphere around him, and he perpetuates the aesthetic conception of man as artist, which he himself personified. “The painter is above all things (I repeat this over and over again) a man. A man who paints. Without being a man, he goes nowhere. He flakes off the canvas. He falls and dies. Human quality!” 30

In some way, the trip enables him to “relive the perceived world,” as the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty stated in those years, and to capture l’air du temps. 31 Every learning is a relearning. Greco relearns to see the world and the man who inhabits the world. This will give him a new impulse, a progressive and essential approach, to move on to the type of work that awaited him, the Vivo-Dito. The artist and the philosopher coincide: there is something healthy about this renewed gaze. Greco enters the living world, contemplates matter, and, with a single gesture, manages to give it a new meaning.

In the testimony that he leaves behind from that journey, we can see the keys to his opening, a concept that was “the great watchword of [his] time.” According to critic Jorge Romero Best, the true artists of their time open themselves to existence. They go beyond what is seen. Informalismo, a movement to which Greco adhered, was “a way of thinking about the world” that admits the most varied, and even opposing, manifestations. 32 This anticipatory projection of an artistic world to be born, where art is in deep contact with life, will provide the conceptual support and the disruptive program of the Vivo-Dito.

I agree with Luis Felipe Noé when he says that “Alberto Greco’s work was his life.” 33 Or, as Roberto Jacoby says: “he lived art in every moment.” 34 In Greco, art and life happen in unison, frantically blurring all limits. Like other artists of the 1960s, Greco understood what was at stake in the aesthetics of his time—the fluidity of the borders around the art-life equation—and he played with it. Greco rewrote his world in a singular poetics rooted in his historicity, his individuality, his subjectivity. This would appear in the Vivo-Dito as a new genre of expression that opened up new aesthetic possibilities.

The episodes that we have studied here are programmatic elements of the Vivo-Dito that took place in Argentina, which allow us to reconsider the origin of Greco’s work. His work is inseparable from the context of a bustling Buenos Aires, a city full of exciting creators. The atmosphere during those years, in which the country was going through a process of developmentalist transformation, a cultural effervescence dominated by a spirit of agitation, and a great voracity for new ideas, was a great stimulus and a propitious environment for innovative creation and the human warmth that Greco so longed for when he was in Europe.

In this article, we have tried to enrich the contextures that Greco carries in his actions, to borrow a term that Marcelo Pacheco recovers from Mari Carmen Ramírez when describing “his local, emotional, and intellectual functions, which come together and break apart on international nets.” 35 This process is rooted in Argentina’s popular dimension, through the most spontaneous, simple contact with the people from the towns of the provinces. It doesn’t matter if Alberto Greco was Argentine or Latin American; what matters is that, in his art, his origin does have a meaning, so we need to understand or locate that meaning.

The Vivo-Dito work Mi Madrid querido (My Dear Madrid, 1964), the only one registered in Buenos Aires, resolves part of this paradoxical nature through nomination. The work’s title refers to Madrid, but its porteño origins are undeniable, with echoes of “Mi Buenos Aires querido,” the classical tango song. That was Greco’s last chance in his native Buenos Aires. He would soon meet Marcel Duchamp in New York.

“Ecrivez ici ‘vive Greco’ et signez,” he asked the demiurge of what would later be called “contemporary.” According to legend, Duchamp “obeyed without flinching.” 36 If Brest’s words had consecrated art’s right to exist in the world, Duchamp’s anointing performs the complementary gesture, giving Greco’s world the right to exist in art. In the last letter he wrote to Lila, Greco assured her: “Marcel Duchamps [sic] wrote laudatory words about me that were read by His Excellency Romero Brest.” 37

The French New York artist was his great model; not only because of his way of seeing art and life (as for others), but because of his way of thinking about them as the same thing. If Duchamp blends art with “the real” through the readymades, Greco doubles the bet: he takes him out of the museum, and into life, through the magical rite of pointing.

Materially, the Vivo-Dito was a circle drawn in chalk, a sphere whose center is everywhere: Madrid, Paris, Buenos Aires, New York, Villa Regina, and every little town visited by Greco during his trip with the Traveling Cultural Exhibitions. Hypotheses and explanations are still being tested to understand the dimension of that sphere in the irreducible place of Greco in contemporary art.