The Writer in Residence series offers scholars the opportunity to conduct research on Latin American art through materials in the ISLAA Library and Archives. For her Writer in Residence project, Rebecca Yuste researched the Argentine painter and sculptor César Paternosto (b. 1931).

César Paternosto lives and works in Segovia, a small and ancient city to the north of Madrid, on the unforgiving plains of Castille. His studio is found up steep steps from the central square, in a neighborhood that hugs the Roman aqueduct and offers unobstructed views of the countryside, yellow in the summer from the unrelenting sun. Slender sidewalks cling to the stoic, severe facades that rise up on either side of the narrow road, paved with cobblestones. When I went to visit César it was early morning, the sound of storefronts opening and the smell of freshly baked bread drifting through the city. Tourists trickled by, taking photographs of the aqueduct before the midday heat became unbearable. The sun was already beating down by the time I rang the bell of an unassuming door.

César answered, his slight figure outlined against the darkness of the vestibule. He ushered me in, away from the mounting heat and into a cool, airy studio. Despite his work as a painter and sculptor, his studio showed few signs of the clutter that popular culture has associated with the creative mind. Instead, the space was tidy and organized: methodical visual experiments placed in a grid on a large counter, a few paintings hung on the walls. Imbued with stillness, the studio exhibited the same kind of cerebral calm found in the artist’s canvases and paper constructions.

We sat down at his desk to talk. A photo of his great-grandson was propped against the wall, and César remarked that he was looking forward to going back to Argentina, where he was born and his children live, to finally meet him. The pandemic had halted most travel plans and, at almost ninety years old, he was impatient to see his family again. We spoke for almost three hours, moving from art to history and back again. His bright eyes darted around his studio as we spoke, finding objects to bring over as our conversation deepened. He showed me small foam blocks—as yet an unfinished work—which he was still rearranging and playing with in search of a suitable spatial structure. We walked over to larger sculptures on the floor, and he told me that the smaller assemblages have become more practical than the cement and steel objects he used to make in New York.

The studio in Segovia seemed far away from that previous life—a restless chronology traversing La Plata, Buenos Aires, and New York—the life I had spent the previous months getting acquainted with through his archive at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA). For a good part of the summer of 2021, I had spent my days poring over newspaper clippings, correspondence, personal notes, loan forms, and exhibition documents. His archive, which lives in nine boxes on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, tells the story of a young Argentine artist who came to New York amidst growing political turmoil in his home country, hoping to find an avant-garde community of likeminded creatives and intellectuals. Sitting across from me, high on the meseta central, surrounded by ancient ruins, César Paternosto showed no signs of the enthusiasm and optimism that marked his first years in New York. With age comes wisdom, and it was clear that he was no longer interested in the type of impenetrable, proud world of art dealers, gallerists, critics, and hangers-on that characterized his time in New York.

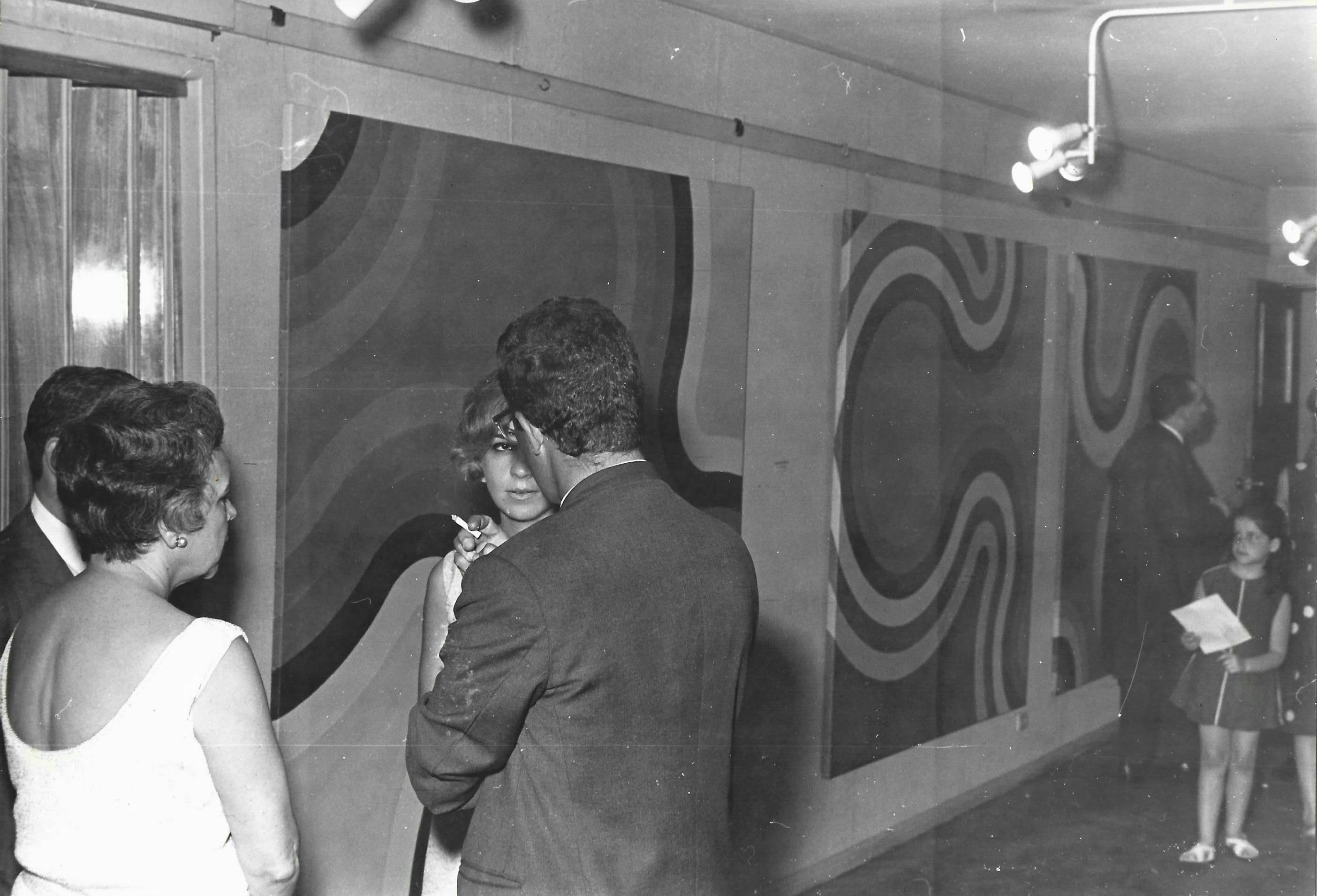

Photograph from the opening of Centro Argentino por la Libertad de la Cultura, November 29, 1965. César Paternosto Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Paternosto arrived in New York in the spring of 1967. The previous fall, he had won the first prize in the Third Córdoba Biennial of American Art in Argentina with his painting Duino, 1966. Alfred H. Barr, Jr.—founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York—was president of the jury and subsequently arranged the purchase of Paternosto’s work for the museum through the Inter-American Fund, as well as inviting the artist to visit the museum. To Paternosto, New York represented a cultural alternative to his native Argentina, where the Revolución Argentina had recently staged a military coup d’état and was closing in on freedom of expression. The Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, one of the most important cultural and artistic centers in Argentina and a fervent supporter of the avant-garde, was increasingly under attack. In response to, or perhaps in anticipation of what was to come, the Argentine art scene became increasingly militant in the late 1960s, staging political protests, happenings and conceptual projects aimed at pushing back against the military regime. 1 The 1966 Córdoba Biennial was mired in protest, as many artists refused to participate. Argentina was becoming an increasingly hostile place to live and work.

It was during this initial trip to New York that Paternosto began to see another way forward, one that offered greater artistic and personal opportunity. Within one year of winning the prize at the Córdoba Biennial, he had relocated his family from Buenos Aires to Manhattan and had begun exhibiting at galleries in Midtown. His first reviews were favorable and generous. As printed inTime magazine in September of 1968:

“César Paternosto — Sachs, 29 West 57th. Singing colors, good craftsmanship, and a deft hand at playing off symmetrical and asymmetrical forms make this Argentine’s New York debut an important one. The works fall somewhere between painting and sculpture, minimal and serial; each is composed of at least seven individual units, some of canvas, others of wood, which are mounted on the wall to form echoing arrangements of color, pattern, and mathematical dimensions.” 2

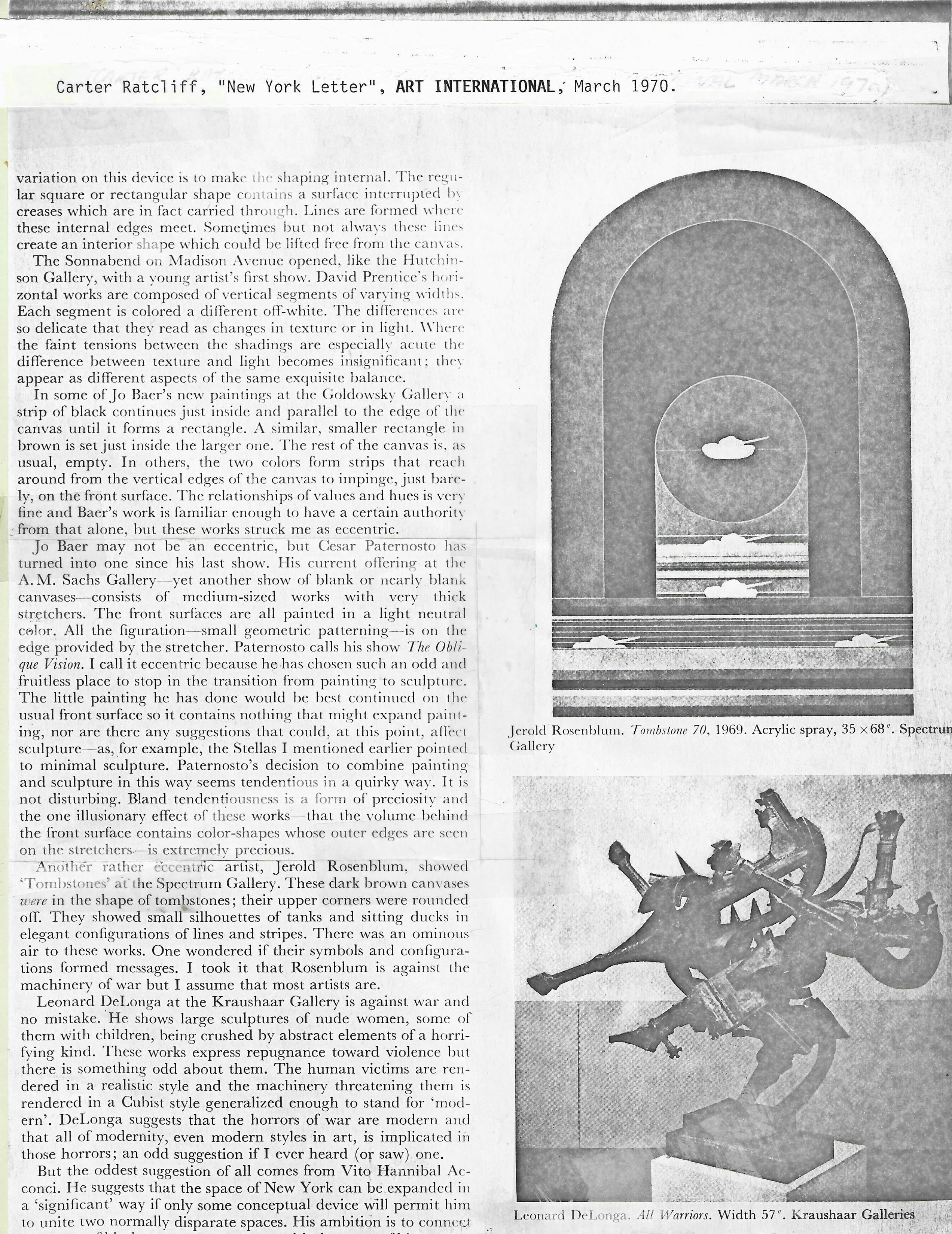

Installation view of The Oblique Vision, 1970, undated photograph. César Paternosto Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Opening announcement for César Paternosto's exhibition The Oblique Vision, A.M. Sachs Gallery, 1970. César Paternosto Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Carter Ratcliff, “New York Letter,”Art International, March 1970, n.p. César Paternosto Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Paternosto had begun his exploration of shaped canvases a few years prior, in Buenos Aires. His visual practice, which began in earnest in the mid-1950s, turned to abstraction by the early 1960s, after a brief foray into the style and work of Antoni Tàpies. A generation or two younger than the artists of MADÍ and Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención, Paternosto was more closely connected to the Grupo Sí back in Argentina. However, upon arriving in New York, he was quickly associated with other artists working in a structural, Minimalist idiom.

By the end of the decade, New York’s Minimalist debate was in full swing. Pushing against Clement Greenberg’s understanding of medium specificity, Minimalists like Donald Judd imagined a new type of artwork: a “specific object,” a term coined by Judd in a 1965 essay of the same name. Minimalism put pressure on a Kantian, disinterested, optical form of contemplation, and instead asked its spectators to engage with physicality and inhabited space. Paternosto’s work, too, bears the influence of this artistic and intellectual moment. In the winter of 1970, A.M. Sachs Gallery presented The Oblique Vision, a show of Paternosto’s recent paintings. There, in a radical move away from his shaped and colorful canvases, Paternosto left the front of his paintings blank. The exaggerated stretchers, thicker than those of a conventional painting, pushed the canvas into the room, exposing an alternate and unexpected site for mark making. Paternosto only painted the sides of these canvases, forcing the viewer to circumambulate around them. Still paintings, but at the same time not only paintings, these works marked a departure in Paternosto’s work, as he engaged with the theoretical and aesthetic cutting-edge of the New York avant-garde.

However, with success often comes controversy. Art News published a glowing review of the exhibition, writing that Paternosto’s paintings “are carefully proportioned to the dimensions of the canvas and balanced with the regular irregularity and poetry of Mondrian. All is achieved through indirect suggestion; a faint halation on the surrounding wall indicates the implicit presence of colors which cannot be explicitly seen, while corners and edges appear to gently disintegrate. All is controlled and understated.” Art News, January 1970, 67–68. On the other hand, Carter Ratcliff, writing for Art International, did not have many kind words for Paternosto’s experiments. “Paternosto’s decision to combine painting and sculpture in this way seems tendentious in a quirky way,” he wrote. Carter Ratcliff, “New York Letter,” Art International, March 1970, n.p. The critique leveled here—namely that Paternosto’s canvases were decorative and offered no serious aesthetic investigation—was one often aimed at Minimalism in this period. Michael Fried, in his infamous 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood,” took on what he saw as Minimalism’s theatricality, which he argued distinguished it from modern art.

Paternosto, caught at the center of these debates, was disheartened by the negative reviews his exhibition received. The sting of bad press was aggravated by the double standard he was subject to, as a relatively unknown, young, Latin American artist in an almost entirely white, US art establishment. At the time of Oblique Vision, Jo Baer—a few years older than Paternosto and one of the only women Minimalists–exhibited her paintings a few blocks away, on Madison Avenue. Baer, like Paternosto, showed works with a mostly blank frontal surface, wrapping colors around the sides. Ratcliff also reviewed Baer’s exhibition, writing, “The relations of values and hues is very fine, and Baer’s work is familiar enough to have a certain authority from that alone, but these works struck me as eccentric.” Carter Ratcliff, “New York Letter.” While he directed some of the same criticisms at both Paternosto and Baer—accusing them of quirkiness, eccentricity, and preciousness—his treatment of the two is ultimately different, because to his mind, Baer’s work “is familiar enough to have a certain authority.” This phrase, and the sentiment behind it, would go on to preoccupy Paternosto for decades to come, as he grappled with his position as a perpetual outsider.

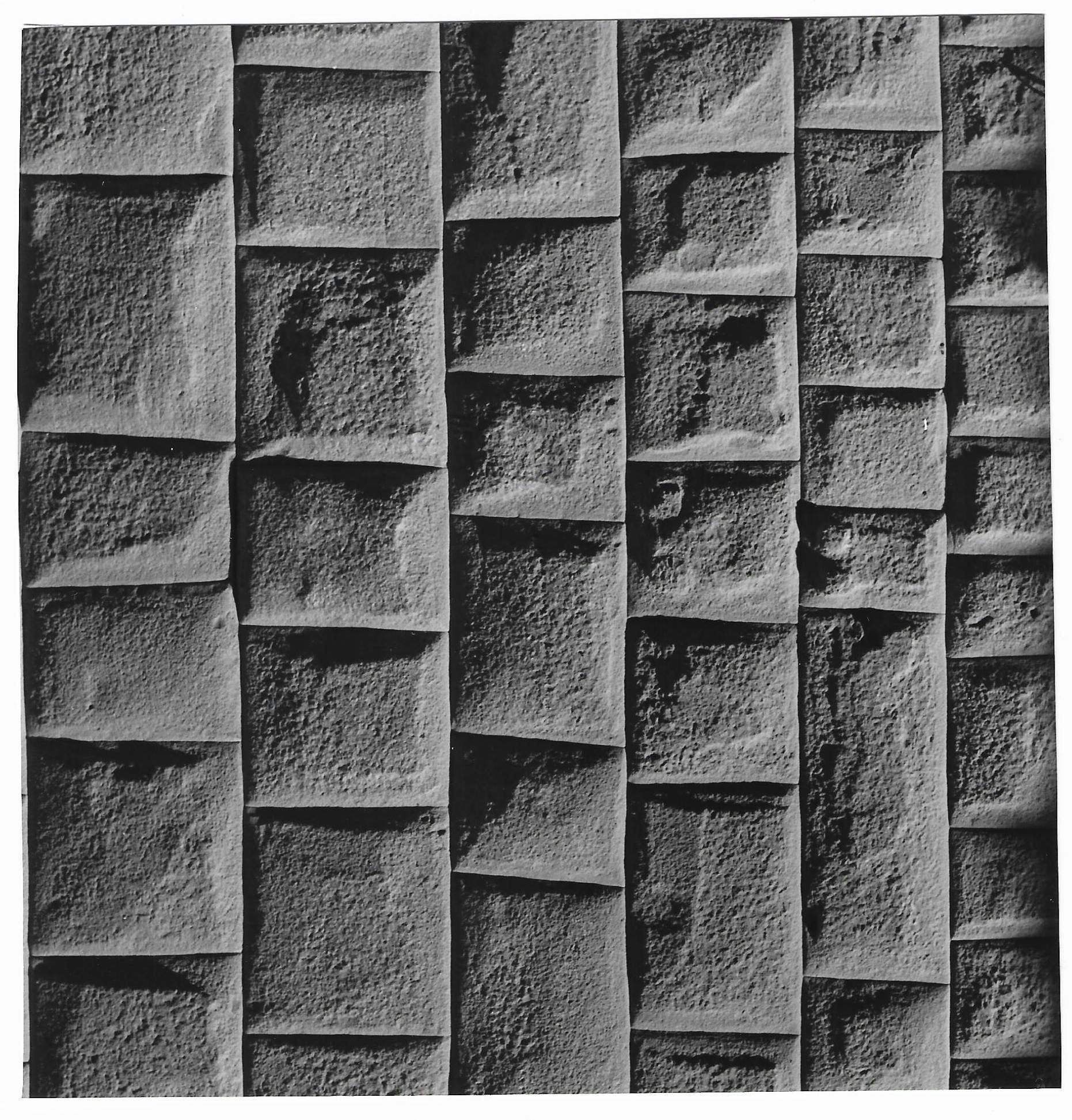

Photograph of a stone wall, undated. César Paternosto Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

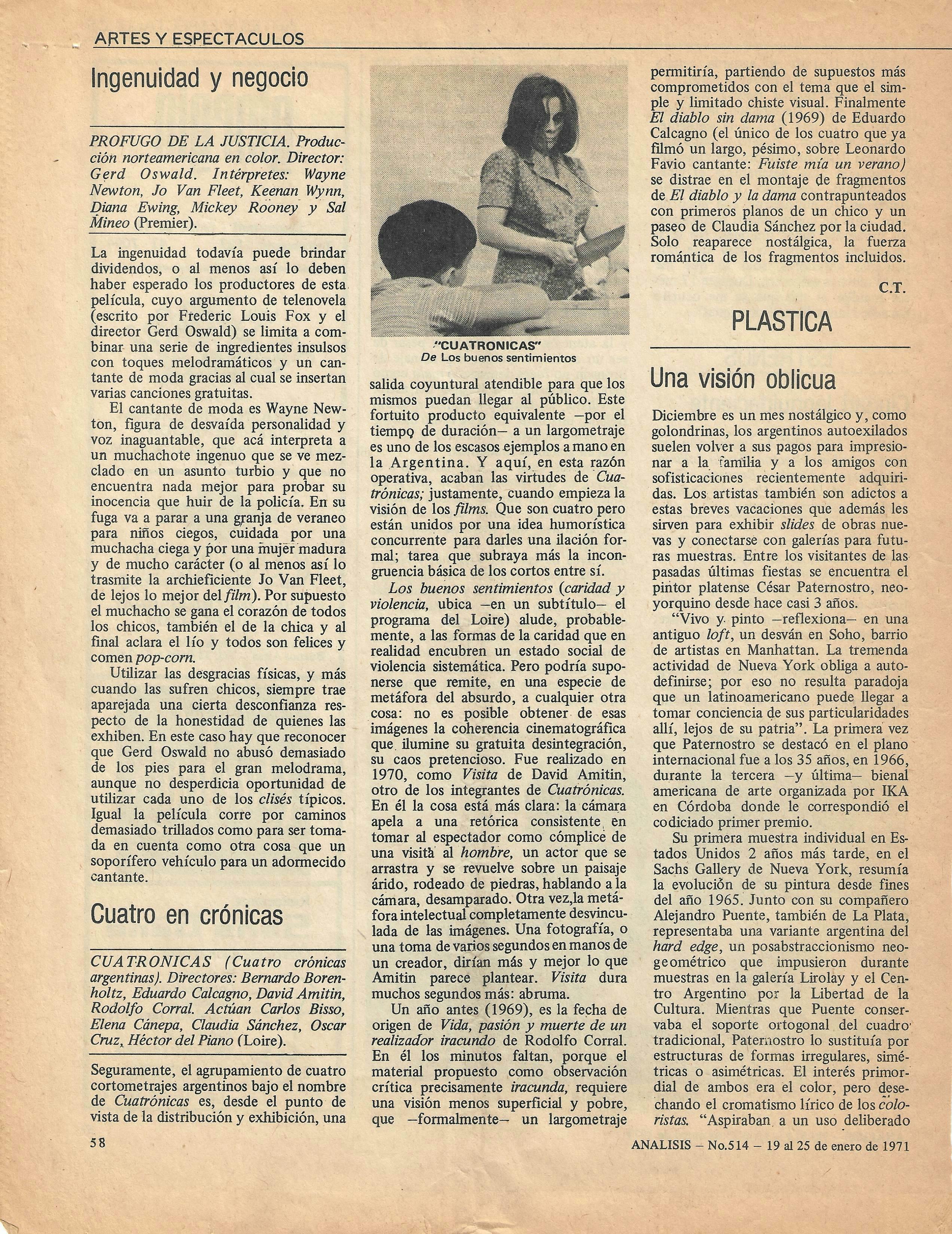

“Una visión oblicua”, Análisis, January 19, 1971. César Paternosto Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

“Una visión oblicua”, Análisis, January 19, 1971. César Paternosto Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

"The tremendous activity of New York obliges you to define yourself; that is why it’s not a paradox for a Latin American to become aware of his particularities there, far from home.”

While his international career took off in the 1970s, exhibiting in Germany, France, Spain, Switzerland, and Argentina with the Galerie Denise René and the Galería Carmen Waugh, there remained a part of him that struggled to negotiate his place in an increasingly global artistic ecosystem. Where did that leave him? In a 1971 interview in the Argentine magazineAnálisis, he said, “I paint and I live in an old loft, a garret in SoHo, an artist neighborhood in Manhattan. The tremendous activity of New York obliges you to define yourself; that is why it’s not a paradox for a Latin American to become aware of his particularities there, far from home.” 3 Paternosto was not completely accepted in the New York art world because of his birthplace, his mother tongue, and his accent. However, as he realized on a 1978 trip to Argentina, returning home was not an option; in the decade of his absence, the military junta and the National Reorganization Process had disappeared tens of thousands of political dissidents.

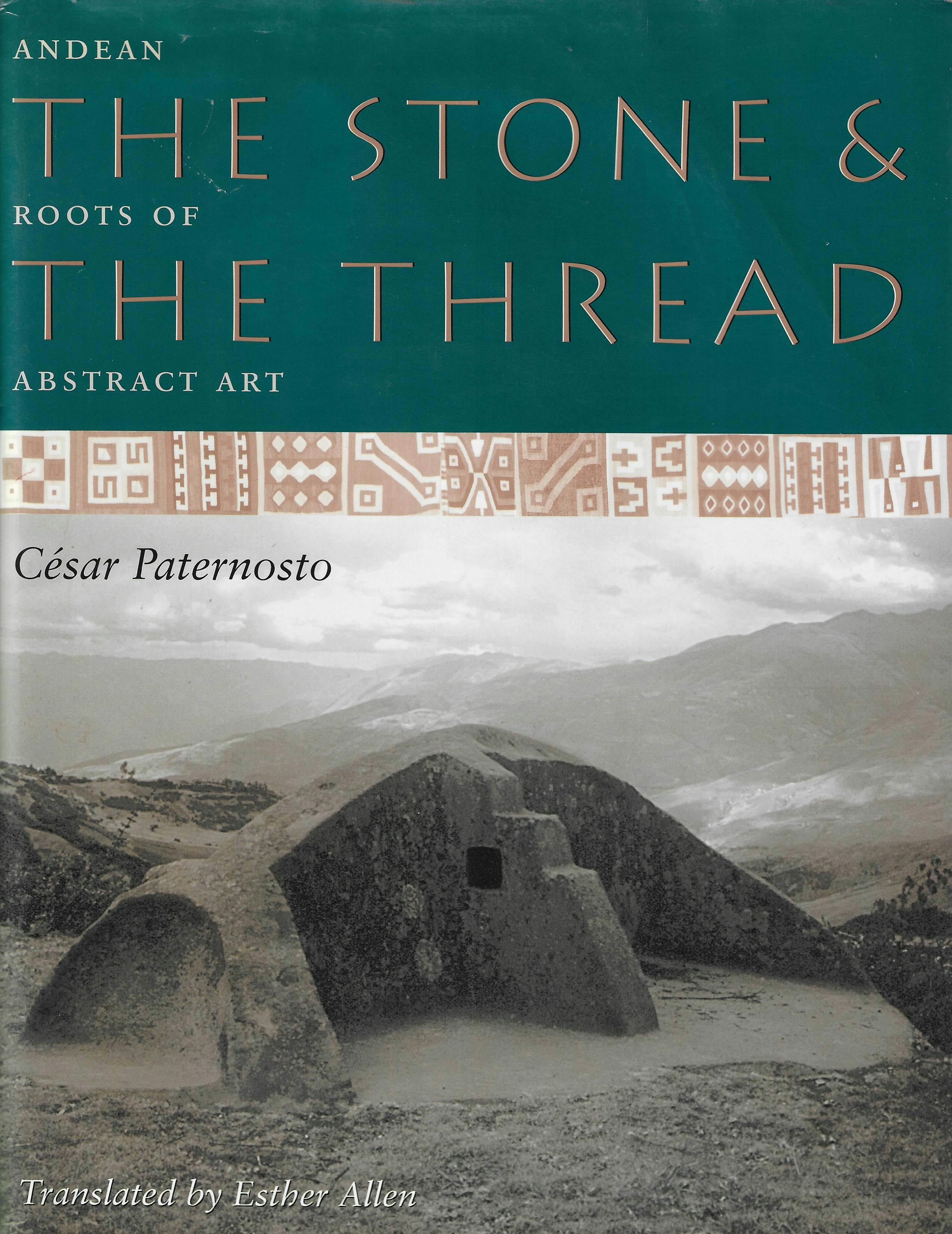

This trip also marked his first encounter with pre-Columbian art in situ. After his visit to Buenos Aires, Paternosto was invited on an archaeological expedition to the Andes by Dr. Kamala di Tella. Together, they visited Tiwanaku in Bolivia before traveling to Ollantaytambo and Machu Pichu in Peru. While Paternosto had always expressed a cursory interest in pre-Columbian art, his confrontation with the monolithic stone monuments, relief carving, and geometry of Andean art touched him deeply. On his return to New York, he began enthusiastically studying the art of the ancient Americas and planning another trip to return to the Andes. He wrote essays on monuments in the Sacred Valley of the Incas, like the Intihuatana in Machu Pichu and the Temple of the Sun in Ollantaytambo, and gave guest lectures at New York University on the monuments he had seen in the mountains. The following year, he embarked on a second visit to the Andes, which would eventually result in the publication ofPiedra abstracta, a study of pre-Columbian art, in 1989.

Paternosto’s turn toward the pre-Columbian and the ancient Americas offered an alternative to the Eurocentric, mythological lineage of modern art in the United States.

Paternosto’s turn toward the pre-Columbian and the ancient Americas offered an alternative to the Eurocentric, mythological lineage of modern art in the United States. Abstraction, instead of being understood as a heroic contribution that traveled across the Atlantic with refugees from the Second World War, one that was based in work by Pablo Picasso and Piet Mondrian, could have its roots in the Andes, in the practices of stonemasons and textile workers and wall painters. He saw Indigenous art as a tremendous source of artistic possibility and, during a visit with young art students in Buenos Aires in 1984, encouraged them to assimilate it into their practice. “The only valid starting point is to embody the syncretic, mestizo culture of our continent,” he told them. “I have no doubts: a spontaneous and autonomous art will come from there, which may or may not coincide with what is happening in Europe or the US, but which in any case will not depend on the ‘model’ that comes from there.” 4 Only by looking back to the ancient past, Paternosto affirmed, would contemporary Latin American artists be able to break away from the control of the northern hemisphere, to make something entirely their own.

Paternosto sought an alternative art history because the reality of the situation, of being a Latin American artist coming to live and work in New York, or Paris, or London, or Madrid, was unwelcoming. As Paternosto playfully wrote in a letter to Lucy Lippard, the New York art critic and historian, one of the only ways to be noticed as an artist born south of the Rio Grande was to come from a country that represented a communist threat. Otherwise, if “you were born in Bogotá, learn English or perish.” 5 Almost a decade later, in a letter written to Elizabeth Aro, a young Argentine artist working in Italy and Spain, Paternosto commiserated with her after hearing about the loneliness and rejection she felt at an international art fair. “There is one thing, the most important, in all your reflections about the trip that should serve as a touchstone: that we Latinos do not have a damn space in the dominant art world. With the exception of market phenomena... (all figurative painters of various stripe) and the pale recognition that some receive post-mortem (no thank you)... Latinos do not exist.” 6

This invisibility wore heavily on Paternosto throughout the 1990s. As opposed to the literary sphere, where Latin American writers like Jorge Luis Borges, Octavio Paz, and Gabriel García Márquez gained prominence in English-speaking circles, visual artists had still not been given the same recognition. “Gone were the days,” Paternosto wrote in response to the question of a boom in the Latin American visual arts, “in the thirties, in which Rivera was more popular and influential than Picasso in the US; or when Pollock saw Orozco as ‘the man,’ one of the greatest painters alive, or when Matta influenced Arshile Gorky in a decisive way; or when Torres-García was seen and respected.” 7 He continued, writing: “Is it not that a young Latin American artist, far more often than not, has to adopt the visual languages first established in the dominant art centers in order to be admitted within the international circuits? Epigonality is, in my view, the unexposed, unseen face of globalization/multiculturalism.” 8 Frustrated with the imitative character of the contemporary art world at the end of the century, with the flattening and cheapening of artistic diversity in the name of development, Paternosto remained firm in his belief that the way forward for a young artist, the only way to move forward, was to look to the past.

Paternosto remained firm in his belief that the only way forward for a young artist was to look to the past.

It was here, in these primal, ancient monuments and ruins, that the alternative could be uncovered. Pre-Columbian art offered not only a new set of themes, iconography, and stories but also a new paradigm for understanding the underpinnings of art. Indigenous motifs, and “abstract, geometricizing designs engraved on bones or stones or painted on cliff rocks dating from the late Paleolithic or the Neolithic, already respond to an urge for the essential, the symbolic, even the transpersonal or conceptual.” 9 Paternosto began seeing abstraction not as a purely formal strategy but instead as a mode of mark-making with a powerful symbolic potential. Interested in the significance of shapes and the meaning in form, his pre-Columbian research and scholarship bled into his artistic practice and served as his “entrance into that incantatory world of ancient symbols.” 10

César Paternosto, The Stone and the Thread, trans. Esther Allen (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996)

Cover of the catalogue DIS SOLVING: Threads of Water and Light (New York: The Drawing Center, 2002). Courtesy The Drawing Center

Into the 1990s and early 2000s, Paternosto leaned into the Andean origins of abstraction. Moving away from stone, he turned to thread, to the ancient textile practices of the Moche, Wari’, Tiwanaku, and Inca peoples. Alongside Cecilia Vicuña, a Chilean poet and textile artist, he explored the affinity between the grid—a grounding structure in his work—and the loom. In these last years in New York, Paternosto dedicated himself to drawing with watercolor pencils, going over the lines he drew with a wet brush, softening the hard edges and creating what Vicuña would come to call hilos de agua, or threads of water. 11 Paternosto’s threads were juxtaposed with Vicuña’s; bits of wool, not quite spun into yarn, echoed the drawn lines, providing a material counterpart to the compositions on paper.

Paternosto’s time in New York ended shortly after the exhibition at the Drawing Center where he and Vicuña exhibited these pieces—threads of water and wool—together. The act of weaving, though, remains central to Paternosto’s practice and the way he thinks about his work. Though he no longer writes about Andean and pre-Columbian objects, the structure of the loom, with its warp and its weft, has provided an alternative framework to the Minimalist grid that he had worked with for so many years.

At the end of our conversation, in that cool, quiet studio in Segovia, he mentioned Gottfried Semper, a nineteenth-century German architect and theorist. Intrigued, I asked him to elaborate; Semper is an obscure figure to the general public but a giant in the world of architectural theory. Paternosto went on, explaining his deep interest in Semper’s theory of the origins of architecture, namely that walls and enclosures come not from trees or branches, but instead from textiles, from weaving. Weaving, Semper maintained, was central to the act of building, to differentiate inside from outside, to set apart early man from the elements that surrounded them. Paternosto has little interest in learning to weave or in making textiles himself. However, that Semperian impulse, the same one found in his work with Vicuña, of going back to an Andean and pre-Columbian antiquity, instead of a Greco-Roman one, of looking to textiles instead of to hard structures, remains in Paternosto’s world, in his intellectual and artistic universe.